Advertising agencies have at last understood that images had to become more interesting to attract the attention of the public. They had to go from the natural to the supernatural, from the real to the surreal, in order to intrigue the onlooker and reach his unconscious in ways which had never been tried before in advertising. These sort of pictures are most effective and have high recall; but usually they are much too costly for the individual to attempt on his own. One would have to resort to painting! Adrian Flowers

Adrian Flowers created images that successfully conveyed the messages intended by advertisers. Often, these concepts originated in the United States, where a large and mobile middle class was being courted and influenced by Madison Avenue firms, operating with a hitherto unheard of sophistication, much of it based on the new science of “Motivational Research”. In his 1957 book The Hidden Persuaders, Vance Packard identified, almost for the first time in the wider public realm, the underlying structures, and architecture, of the consumer society. He revealed the widespread use of psychological triggers and subliminal messages in advertising, designed to induce desire amongst buyers, without their being aware of it. Products were no longer straightforward products, but brought with them the promise of higher social status, and new and glamorous lifestyles. With its cover illustration of a bright red apple impaled upon a fish hook, The Hidden Persuaders categorised psychological needs—including weaknesses, fears and anxieties—shared by people, and tracked how these were addressed by advertisers, often in a cynical way. These hidden needs included emotional security, a search for identity, self-gratification, love, sex, power and immortality. Advertisers found that particular colours, such as yellow and red, were effective, as were symbols and logos that had dream-like qualities.

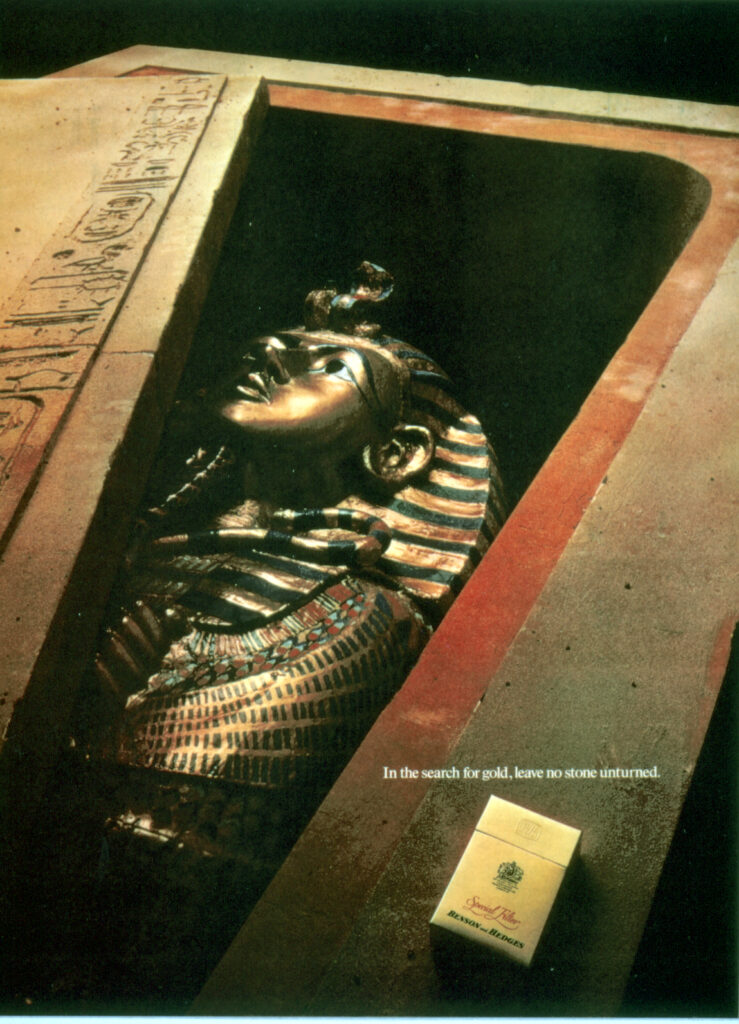

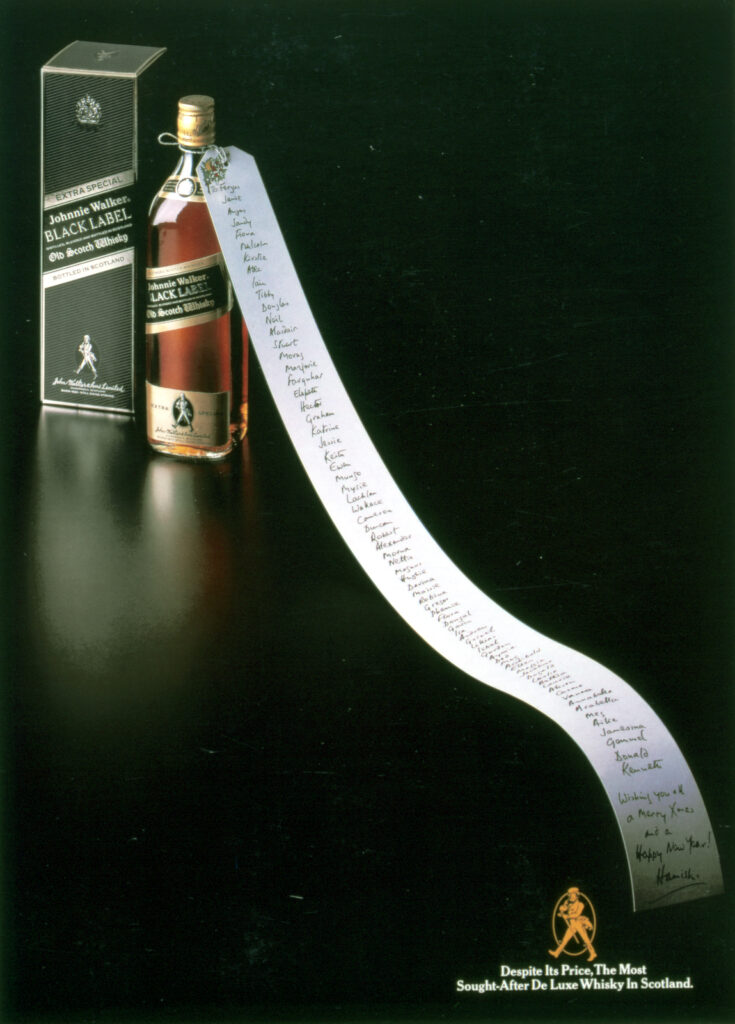

The techniques used were so effective they often contributed to impulsive and self-destructive behaviour, while also raising company profits. Based on the work of the Austrian-American Ernest Dichter, whose credo was to promote a lifestyle of corporate hedonism, Motivational Research and focus groups were among the methods used to develop brands. However, after Packard’s 1957 exposé, those using MR became more subtle in their approach. Brands were created and manipulated through the use of imagery that often sought to eliminate feelings of guilt in the consumer—at spending money on products that could be seen as indulgent, or even self-destructive, such as cigarettes or alcohol. Advertisers learned to change imagery and messages at will. Gender and gender manipulation was also regularly used. Society was divided into different classes, mainly, but not entirely, depending on income, and the burgeoning middle class became the key target audience for advertisers. Although intended, and read, as a critique of consumer society, Packard’s book had an equal and unintended effect, providing a concise and readable account of how advances in psychological profiling made it easy for advertising companies to earn their keep. Young people going into advertising could read The Hidden Persuaders, and knew instantly what was going on. Predictably, major advertising companies, particularly Ogilvy, cast cold water on Packard’s sensationalist style.

Both MR research and the advertising campaigns that resulted were imported into England during the 1950’s, into a country where class divisions were still largely in place, and where upward mobility was more restricted than in America. But the campaigns were no less successful. Paradoxically, it was in photography and advertising that people from working class backgrounds could often enjoy a new-found freedom and social mobility, and also earn a good living. The cockney photographer portrayed in Antononini’s film Blow Up was based loosely on real-life photographer David Bailey. While Brian Duffy, who worked as an assistant in the Flowers studio, became part of what Norman Parkinson dubbed ‘The Unholy Trinity’, a triad that also included Bailey and Terence Donovan.

In this world, Adrian Flowers occupied an almost unique position, in that his own family heritage included several generations of professional photographers, going back to the late nineteenth century. Flowers’ lifestyle was glamorous, and his studio, in Chelsea’s Tite Street, operated with a degree of professionalism and organisation that was lacking in many other studios in London. At it’s peak, the Adrian Flowers studio was considered the best in the city, and with London one of the world’s centres for advertising, there were good opportunities in the heady days when Motivational Research had turned advertising into a sophisticated and intellectually-driven industry.

Text: Peter Murray

Editor: Francesca Flowers

All images subject to copyright.

Adrian Flowers Archive ©