Adrian Flowers in India May 1963 Job Nos. 4551 – 4558

On May 1st 1963, having flown from Kenya to Mumbai (Bombay), Adrian Flowers and his art director Terry Flounders checked in to the city’s grandest hotel, the Taj Mahal. While appreciating the large rooms with their overhead fans and air conditioning, Flowers found the city overwhelming: “so many people, 4 ½ million, all in the streets. Men in loose white shirts and trousers, girls in colourful saris, many unfortunates lying or squatting about. The whole place is buzzing.” He took snapshots as they drove through the city, focusing on quintessential details: cyclists, double-decker buses, shop signs, and an old horse-drawn ‘Victoria’ carriage, a relic of the Raj.

The following morning the pair were up early, for a long flight south to Cochin [Kochi], and a short stopover before they boarded a plane to Coimbatore, a town in the mountains north-east of Kochi. There they were met by a Mr. Simmonds, who took them to Giles Thurnham’s house, where they were to stay for the night.

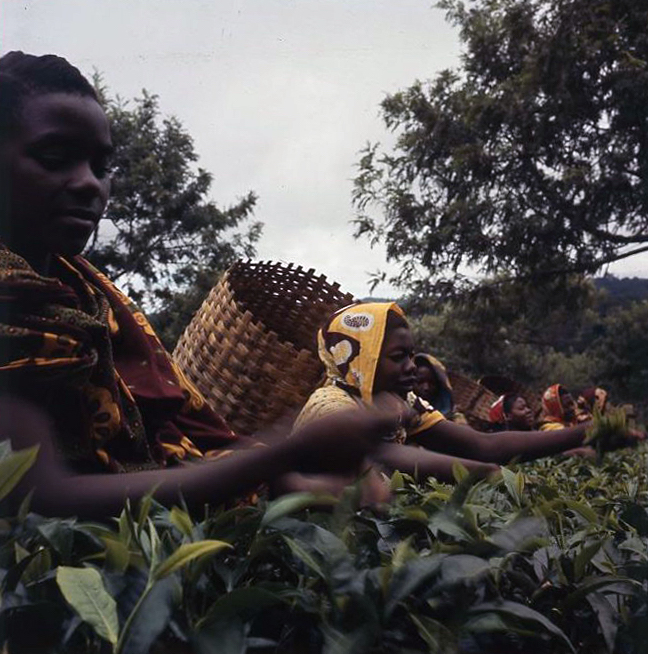

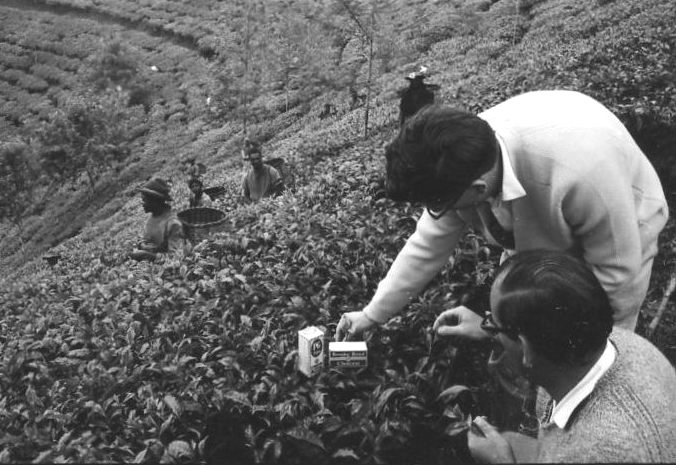

Their third day in India was again an early start. After a six-hour car drive in a Plymouth shooting brake, they arrived in the High Wavys mountains [Meghamalai], some two hundred kilometres south of Coimbatore, where they were to stay for three nights. Flowers summed up the estates: “ ‘High Wavys’ and nearby ‘Cloudlands’ (good title for ad shot, but no time), very attractive estates carved out of jungle. It was there that both V.P. and contour planting were begun.” A Brooke Bond magazine ad from 1956 exhorted Indians to thank Lord Bentinck for introducing tea to India in the early nineteenth century, a sentiment that overlooked the environmental degradation caused by the conversion of thousands of acres of forest into tea monoculture. As well as rows of lush tea bushes, Flowers’s photographs show serried ranks of pesticide sprayers, and lines of tea pickers, all women. The majority of tea pickers were, and remain, relatively impoverished, in contrast to their employers, who enjoyed a relatively privileged lifestyle. However, unlike Kenya, where the former Brooke Bond estates are now owned by a Luxembourg-based investment fund, the tea business in India has transitioned more smoothly from colonial times to independence and is now owned by Hindustan Unilever, who market products such as Green Label, Red Label and Kora Dust. India’s development as a nation is reflected in the success of Hindustan Unilever. In 1963, the Chairman was V.K. Murthy, who had risen through the ranks as a tea salesman.

On arrival at High Wavys, Flowers and Terry had a late lunch with the estate manager and his wife, Ernest and Audrey Haggard. “Another pleasantly designed bungalow, although not so well appointed as the others. In fact I think they vacated their room for us. Wonderful view. Family comprised a little boy of 3 called Adrian, who was very shy indeed, and could hardly speak English because he spent so much time with the servants; and a baby girl. Audrey (the mother) . . seemed pretty fed up, the only white woman on the estates and for hundreds of miles probably. Ernest, a strange mixture. ‘Home’ is somewhere near London, but in fact he was born in India and was here all the war in Darjeeling where he was educated probably with Indians to a large extent . . I noticed how very ably he spoke to the Indians in their own tongue, which is Tamil in Southern India and Hindi in the north, most that is. He would speak both.”

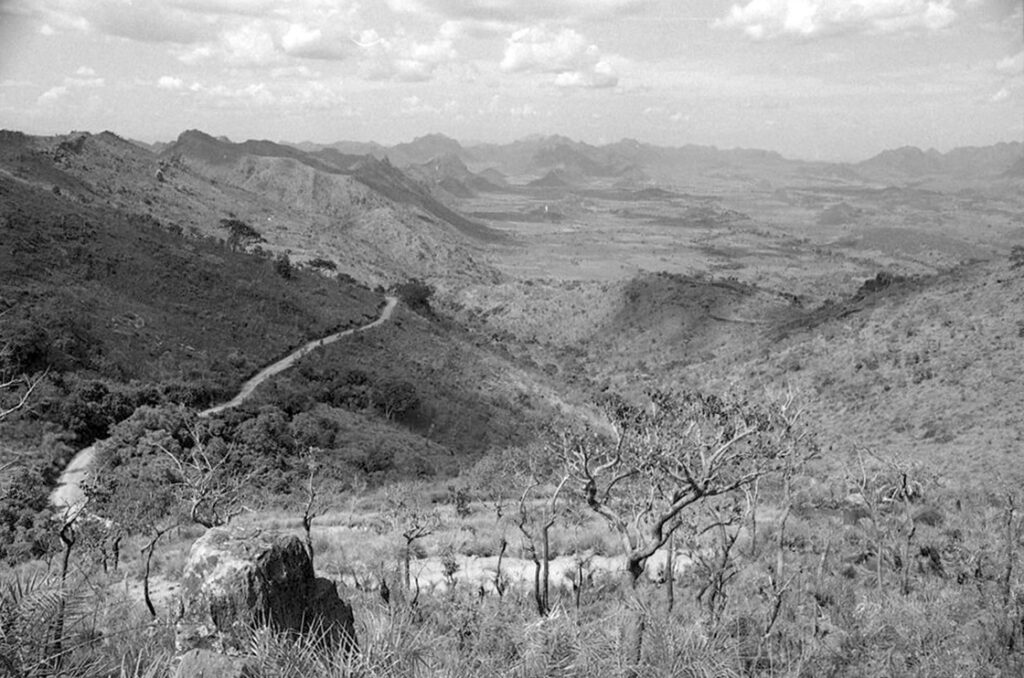

The next day they were met by Coutier, an Indian manager in charge of the neighbouring estate Vennier. “He showed us V.P. nurseries and shearing pluckers and then took us to his place for lunch where we met his striking wife Rani (short for Maharani). We are travelling now, just above the most extraordinary clouds. I wish I could take a picture, but it is strictly forbidden. There are notices all over the airports as well. That afternoon when the light had faded from a photographic point of view, Coutier took us to a point where, by walking up a hill for a mile, we arrived at the edge of the escarpment. An almost vertical drop of 5000’. Incredible view of mountains and troubled skies. On one side, some 50 miles away, a tremendous thunderstorm was in progress. I took a few TX135 shots with 28mm, but they will be of no use unless blown up enormous.” They seem to have enjoyed themselves at Coutier’s, and the following day Flowers was taking photographs on Ernest Haggard’s estate. “Did not see Coutier or Rani again. So no dancing.”

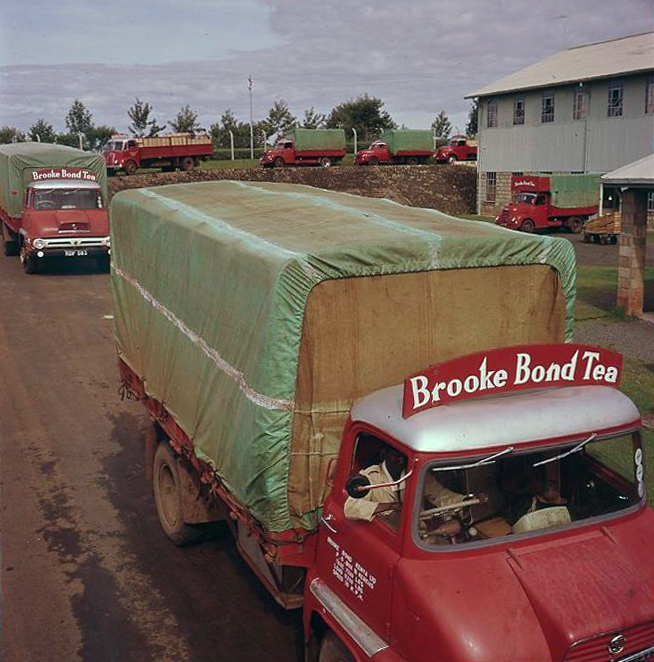

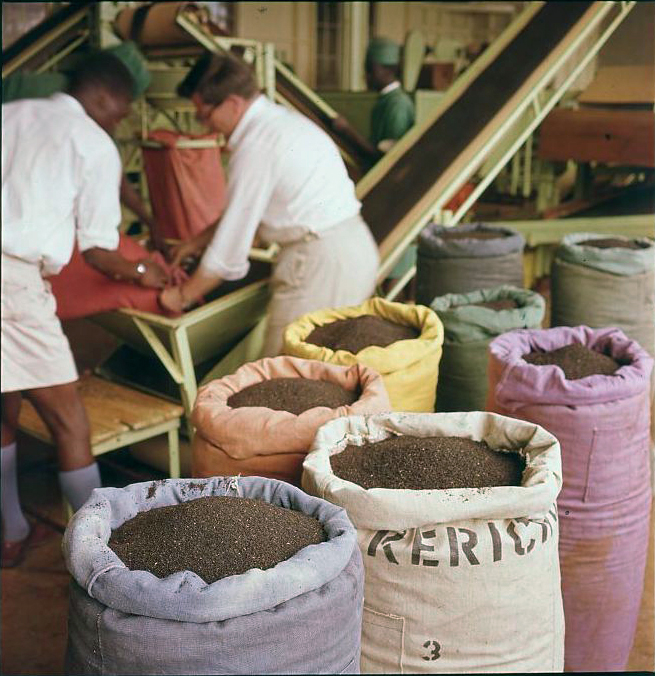

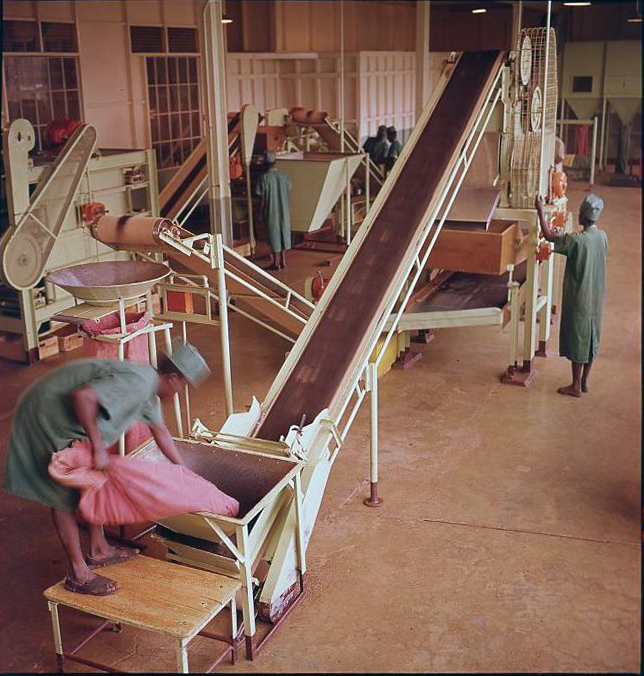

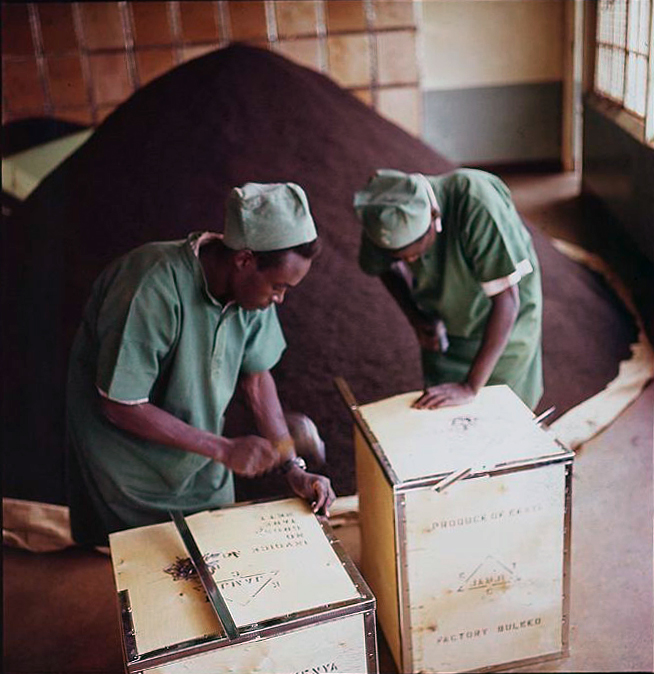

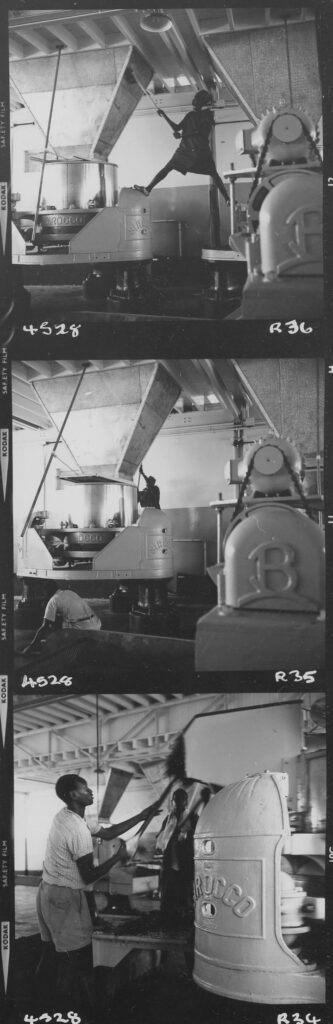

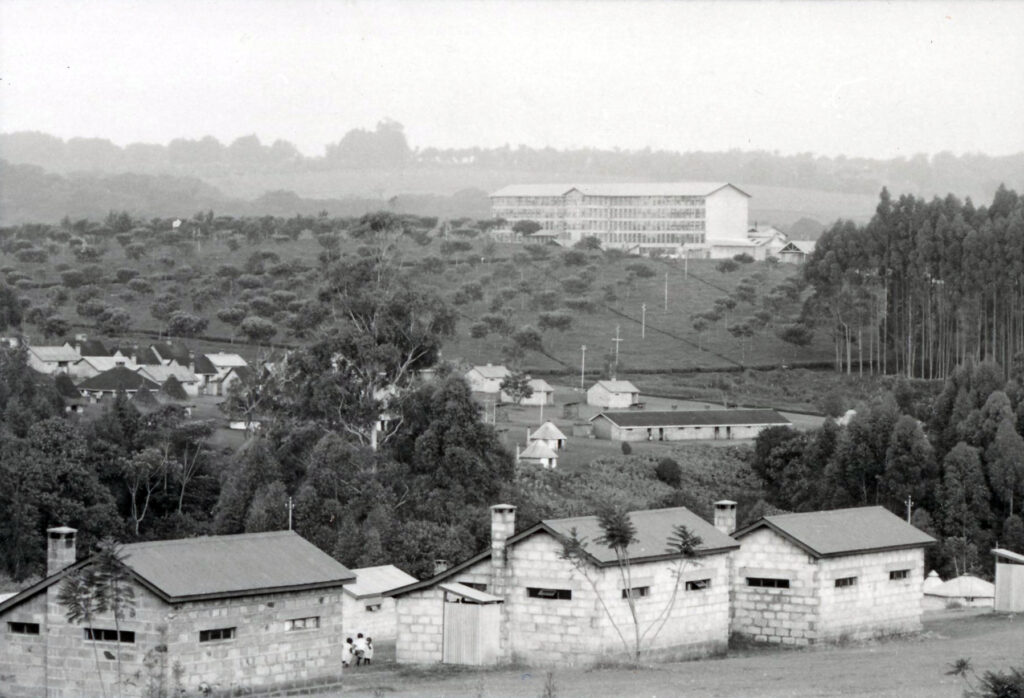

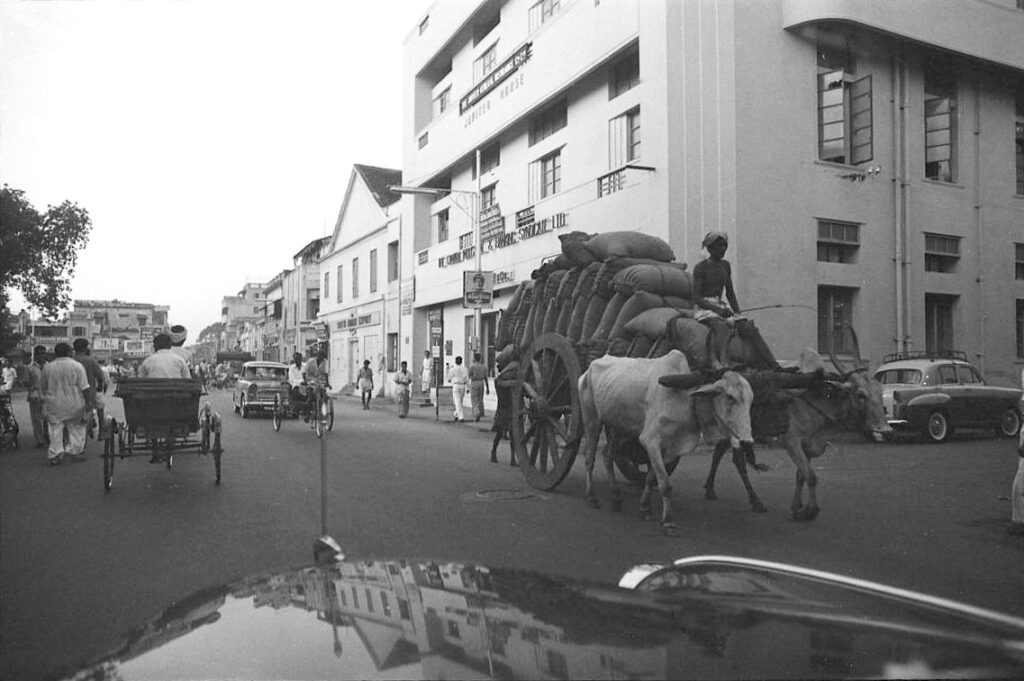

Flowers photographed all stages of tea production, from the VP (Vegetative Propagative) nurseries, through to the final packing into plywood tea chests. He also documented the company’s coffee processing plant, photographing coffee being packed in large tins, ready for shipping. The factory was managed by a combination of European and Indian technicians and managers. The tins were made in the factory, as were wooden crates and packets. Although the factory was modern, with up-to-date equipment and conveyor belts carrying tea chests onto lorries, outside the building an older India survived, with white oxen drawing wagons laden with old oil drums.

The following morning, Flowers took what he described as the most important shot of the trip: “waddery around the Motherbush S.A.6”. He wanted to take photographs of teacups and saucers with the motherbush in the background but was disappointed with the standard of cups available. “We hope to buy some in Calcutta.” After lunch, they travelled to the Anomalian mountain range, and then onwards to the hill station Valparai, still in the Coimbatore region of Tamil Nadu. With an elevation of three and a half thousand feet above sea level, it was hotter than the estates at higher altitudes. Valparai is at the centre of estates that include Nadumalai, Stanmore and Nallakattu.

By Friday May 10th Flowers was in Chennai, [then called Madras]. “I’m writing in my room in the Connemara Hotel, of all places, in Madras. The temperature outside rains between 95 and 105. I’m beginning to like it. . .We were met just now at Madras airport by Mr White who brought us here and then to the government office. There we argued for 20 minutes in order to sign forms in order to buy an expensive drink! Doesn’t seem worth it. . . Passports were taken from us in Bombay to be sent to Calcutta to get special permission to get into Assam etc so that we are not delayed. The red tape is fantastic. . . In a few minutes Mr White is calling for us and is taking us out to dinner. Tomorrow morning he has promised to show us a few places.”

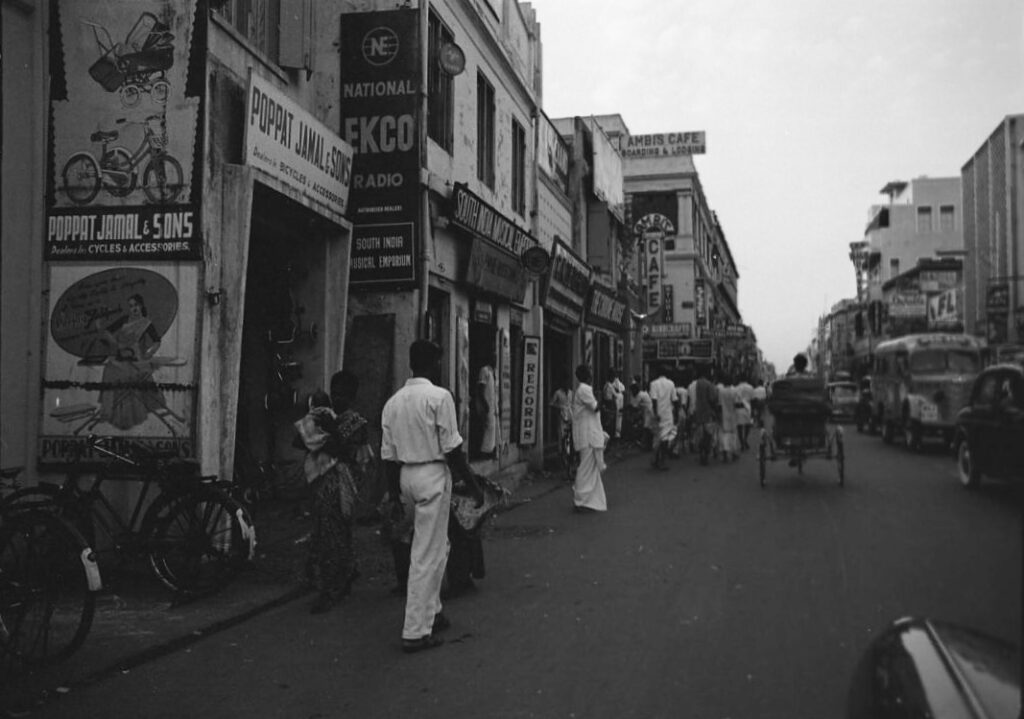

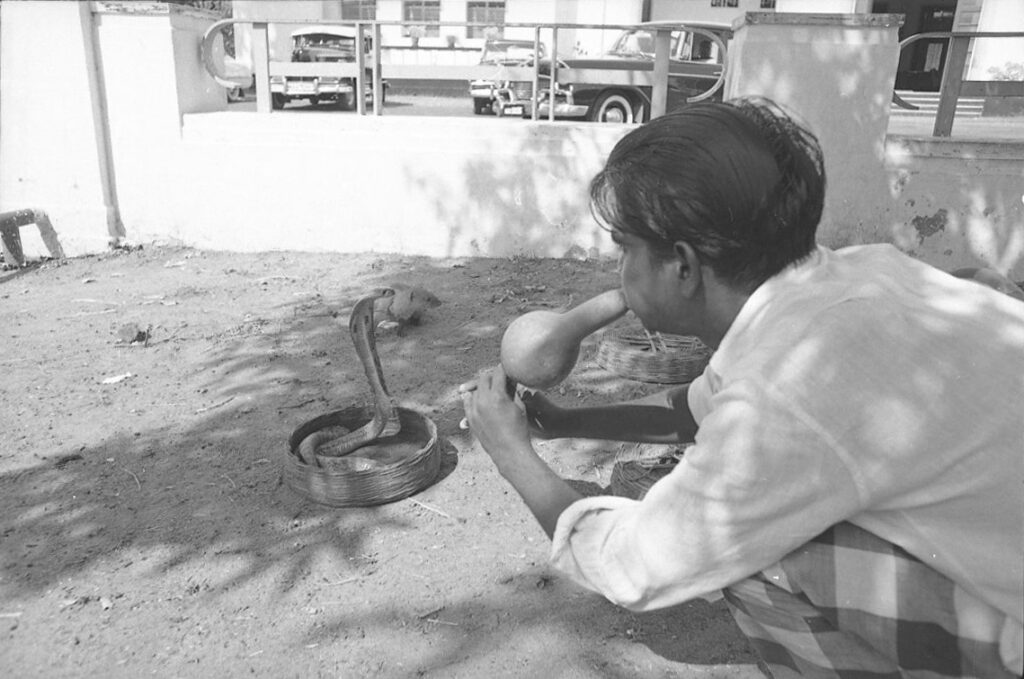

Touring through the streets of Chennai, Flowers again photographed everyday details; horse-drawn carriages dating from Victorian times, a traffic policeman shading himself with an umbrella, an aging Austin Ten car parked outside a row of shops. The streets were crowded with traders, women dressed in saris, and men in white shirts and trousers. There were awnings to shield pedestrians from sun and rain, while cattle ambled past the Rainbow Hotel. His own lodgings were more palatial; he photographed the high ceilinged bedroom with mosquito nets over the beds. The Parrys district provided ample subject matter: Several photographs show the motley shops lining NSC Bose Street, looking towards the distant towers of the High Court. Several buildings are now gone, including the ornate Esman Building with its watch shops and Gramophone House, replaced, as is much of Bose Street, with a modern-day medley of hoardings, cheap plastic signs and opportunist pavement hawkers. The traffic in 1963 was mainly composed of bicycles, rickshaws and horse-drawn jutkas, with a few modern saloon cars; nowadays motorcycles and yellow three-wheel taxis throng the busy street. Flowers also photographed the corner of Periyar Salai, with the white clock tower of the Ripon Building in the background. and the grand Chennai Central railway station, with its Victorian clock tower. A visit to Fort St. George was also part of the tour, with its museum of armaments and portraits of generals and viceroys, and the nearby Anglican church of St. Mary’s, with its memorial plaques recording the many who had died in pursuit of an imperial vision.

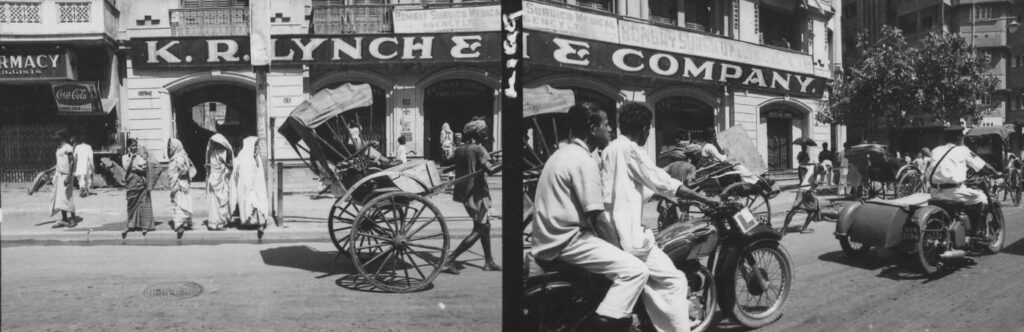

The following day, May 11th, Flowers flew north to Calcutta (Kolkata). During his time there he again ventured out with his camera. The streets were wide and dusty – a far cry from the traffic jams of today’s Kolkata. Several photographs include signs for companies still in business, such as K.R. Lynch., a surgical supplier on Chittaranjan Avenue, opposite the School of Tropical Medicine. Flowers snapped a lorry full of soldiers looking suspiciously at this English photographer. He took in tourist sites, photographing the Pareshnath Jain Temple, on Badridas Temple Street, a building dating from the 1860’s with ornate gardens and interior halls lined with mirrors.

After Calcutta, Flowers and Terry flew to Mohanbari, a town in Assam, in a twin-engined Fokker Friendship. On a previous flight, their C 47 Dakota had hit turbulence in an electrical storm, with ensuing chaos: “Baggage fell all over the place. Teapots and cutlery onto the floor in the kitchen. Children screaming. The pilot was game and threw the machine nose down, and then after sliding about crab fashion, made quite a reasonable landing.” On that flight they were accompanied by Mr. Nagarajan, a director of Brooke Bond, who ‘quite enjoyed’ the spectacle. The Fokker Friendship encountered no turbulence and the flight to Mohanbari went well. Returning to Calcutta, they stayed at the Grand Hotel, which Flowers described as ‘enormous’, with a long walk from the lift to their rooms; their Antler suitcases stacked three high on a porter’s head. After dinner they watched a second-rate cabaret. “We were able to drink thank goodness. Calcutta is ‘wet’. The price of a drink is incredible. Bottle of scotch £10! Indian beer is not too bad though, and reasonable.”

The following day, they were taken on a tour of Calcutta by a Mr. Gaush, in a Dodge shooting brake. Gaush started by showing them the more affluent areas, then the middle class sections, then the poorest districts: “There are enough poor wretched humans in this one town to make the whole of life on this planet a mockery. Every conceivable unpleasant sight, pavement dwellers all over the place, tolerated by the others. ‘The unconcern of the occident’ someone said.” In 1963, the city of Calcutta had eight million inhabitants, with a water supply designed for a quarter that number. Flowers gave Gaush films for safe keeping, then he and Terry took a flight back to Coimbatore and the High Wavys estate, to photograph the famous Mother Bush: “On our way to the airport we called at the best shops to buy china. Terrible stuff. The third place was fruitful enough for us to buy something.”

After High Wavys they went on to Anomalia where they stayed at the home of Roger and June Hands, and, under pressure for time, cancelled lunches that had been arranged in order to concentrate on photography. Flowers chose a small group of female workers to pose for the tea picking scenes. He was aware that the women were from a low caste in the Indian social system, but the following day they showed up, all dressed in their best saris. [photograph top of page] “It is quite tricky getting Indians or Africans to smile. They all think they should be serious in a photograph.” The following day, Flowers and Terry returned to Coimbatore, a four hour drive. ” It took nearly 2 hours to slowly get down the 40 hairpin bends to the hot plains below.” This time, they could not stay with the Thurnmans, as there was a UK trade delegation visiting, so they were guests at the England Club. ” . . we met some of them in the bar, in fact all the local (Southern Indian European) talent, about 20 odd people. I found myself talking to a charming over talkative woman who told me she had wanted to be an actress and sing comedy…. etc.” That was their last day in India; they then returned to Nairobi, as the weather had improved in Kenya and photographing the tea estates was now feasible.

Flowers’s journey in India had taken him the length and breadth of the continent. Travelling from Mumbai [Bombay] in the West, to Chennai [Madras] on the Indian Ocean, then to Kolkata [Calcutta] and Assam in the North East, he had stayed in some of India’s grandest hotels, and photographed the estates, factories and godowns (warehouses) of Brooke Bond. In addition to modern factories, his eye was drawn to a quintessential India that was passing, a world of horse-drawn carriages, rickshaws, ox carts and snake-charmers. He enjoyed meeting the tea estate managers and their families, but missed his own home in London. Meanwhile, back in St. John’s Wood, in addition to looking after their three young children, Angela was also keeping an eye on the photographic studio, where Valerie and David were processing the rolls of film sent home by Flowers.

Text: Peter Murray

Editor: Francesca Flowers

All images subject to copyright.

Adrian Flowers Archive ©