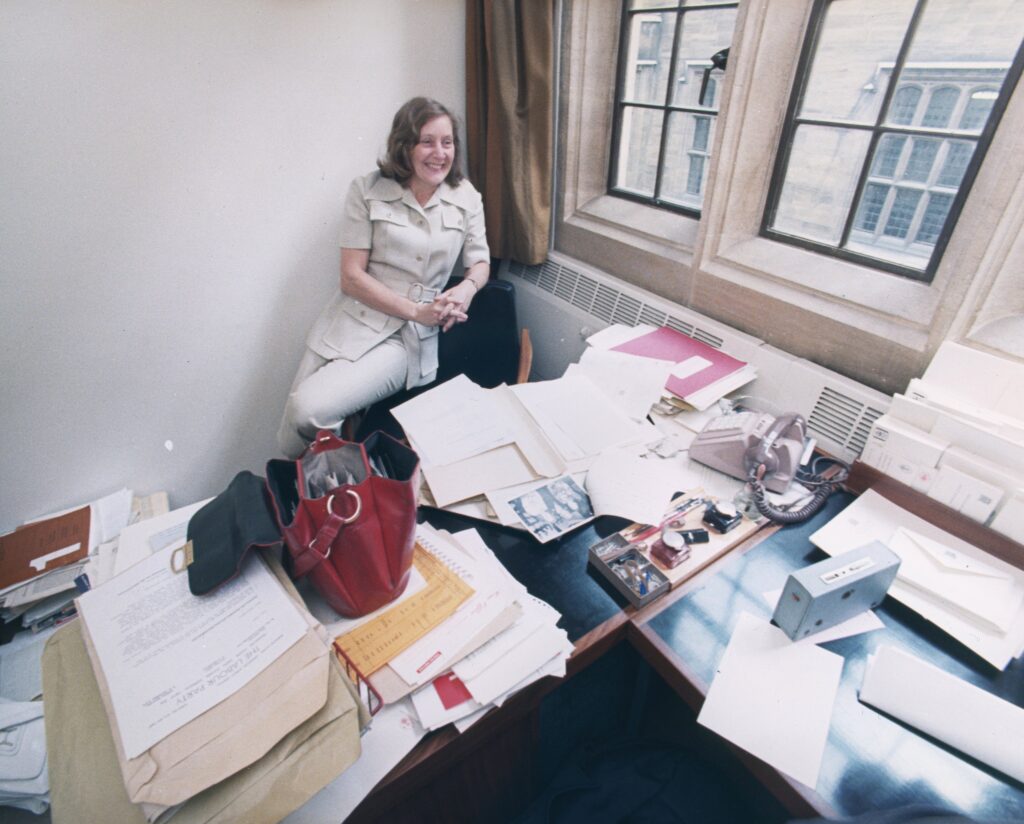

Baroness Williams of Crosby (1930 – 2021)

photographed by Adrian Flowers, for the Observer, 20th July 1973

On 20th July 1973, accompanied by his son Matthew (2nd assistant at that time, 1st assistant was Steve Garforth – see previous post from July 2020 ), Adrian Flowers brought his camera equipment to the Houses of Parliament at Westminster, to photograph Shirley Williams, for an article for the Observer. Williams at that time was poised to become the first woman prime minister, but in the event she stepped aside to allow James Callaghan to take up the leadership of the Labour Party. The photographs taken in 1973 provide a vivid record of a woman who was at the heart of British politics. Dressed in a white safari suit, her red leather handbag sitting on a desk strewn with papers and files, Williams was totally at ease with the camera. She had long been one of Flowers’ heroes, and her championing of progressive policies on education, race relations and society tied in closely with his own views. Just three weeks earlier, in Parliament, Williams had railed against the new Immigration Act, the wording of which was open to varying interpretations. She pointed out that people stopped for minor traffic offences were being taken to police stations and questioned about their status as immigrants: “There are particularly sensitive areas which the House must consider. One of these is the relations between the immigrants and the police. The relations between the police and in particular the Asian community have, by and large, been good. . . Civil liberties do not erode at the top: they erode at the bottom, among the most under-privileged, the most poor, the least popular. If the House cares—and I believe that it has always cared—about civil liberties, it must tonight take the not wholly popular but deeply important step of satisfying itself that the constitutional rights and civil rights of these people have been adequately protected by us.” [Hansard HC Deb 26 June 1973 vol 858 cc1405-70] But a few days later Williams, ever mindful of the well-being of all sectors of society, was seeking improved allowances for police officers based in London. As a member of Parliament, and then of the House of Lords, Williams devoted almost her entire life to politics and public service.

Born in 1930, Shirley Williams (née Brittain) was brought up in a resolutely left-wing household, albeit one in which social commitment was matched with a degree of prosperity. Her mother, Vera Brittain, originally from Staffordshire, was a prolific author and political activist: in 2014 Testament of Youth, an autobiographical memoir of her experiences as a nurse in the First World War, was made into a film by the BBC. Her daughter’s life was also shaped by war. Evacuated from Britain during WWII, Shirley Williams spent several years in St. Paul Minnesota, where she attended St. Paul’s school. Her father, George Catlin, while lecturing at Cornell University in the early 1940’s, was an advisor to American presidential candidates. Returning to Britain after the war, Williams attended St Paul’s School in London (where her father had also been educated) then studied at Oxford, before working as a journalist, and then entering politics. Much of her life was dedicated to breaking down those barriers of class and privilege that had paradoxically, during her formative years, given her access to inspirational figures including T. S. Eliot and Jawaharal Nehru. There were other paradoxes in her political life; motivated perhaps by her Catholic upbringing, during the 1960’s she opposed liberalising divorce and abortion, and was later opposed to gay marriage. As Minister for Education in James Callaghan’s Labour government in 1974, she championed comprehensive education but cut resources for teacher training.

Although she served in the Labour governments of both Wilson and Callaghan, she resigned from the Labour Party in 1981, to found, along with three other rebels, the Social Democratic party, which later merged with the Liberals to form the Liberal Democrats. Her first husband Bernard Williams, who she married in 1955, was an academic and later a philosophy don, while her second husband Richard Neustadt, like her father, was an academic who served also as advisor to American presidents including J F Kennedy and Bill Clinton. He and Williams met during her time as lecturer at the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard. After a distinguished parliamentary career, in 1993 Williams was appointed a member of the House of Lords, a post from which she resigned in 2016. Her own autobiography Climbing the Bookshelves was published in 2009. She died on April 12th 2021.

Text: Peter Murray

All images subject to copyright