Photograph by Adrian Flowers

Among Len Deighton’s best-loved cookery books are Ou Est Le Garlic? (1966), Basic French Cooking (Jonathan Cape 1979), ABC of French Food and Basic French Cookery Course. However it is his Action Cook Book, first published in 1965 and later re-issued as French Cooking for Men, that best retains the fresh and breezy appeal of ‘sixties London. The Action Cook Book is a compilation of Deighton’s ‘Cookstrips’ published in the Observer between 1962 and 1966. The deceptively simple graphic style and hand-drawn fonts of the Action Cook Book remain innovative today, and have inspired a new generation of publications in which comic-book art and texts are combined. In 2015, celebrating the success of the 1960’s Cookstrips, Len Deighton and his son Alex began collaborating on a new series for the Observer Food Monthly Magazine. While retaining Len’s style of simple images and hand-drawn lettering, these new strips are drawn by Alex, and have introduced readers to a wide range of world cuisine.

With its cover designed by Raymond Hawkey and photography by Adrian Flowers, the Action Cook Book was stylish, modern and met a growing demand among readers for information on good food. Its success led to a second Deighton cookbook, Ou Est le Garlic? As a child, Deighton had learned inventive cuisine from his mother, Dorothy (née Fitzgerald), who occasionally cooked for a London nightclub. Using ingredients exempt from food rationing, she created dishes that were given colourful names in the menu, such as ‘sweet and sharp tongue’. In an interview with John Walsh in the Independent (23 Oct 2011), Deighton described how, during summer vacations from art college, he had worked as a kitchen porter at the restaurant in the Royal Festival Hall: “One day I was mopping the floor when the fish chef asked me if I would do some jobs for him, as his assistant hadn’t arrived. My first task was skinning Dover soles. I must have been a good student because he then showed me how to fillet them. From then onwards, my days were spent as unofficial assistant to the fish chef, though I was still paid only porter’s wages. I once asked my chef why he’d chosen me for this sudden elevation. He said everyone had noticed the way I ‘hung around watching the cooks’. He was right.” In addition to summer jobs in London and Paris, Deighton also attributed his culinary education to Philip Harben, television’s first celebrity chef.

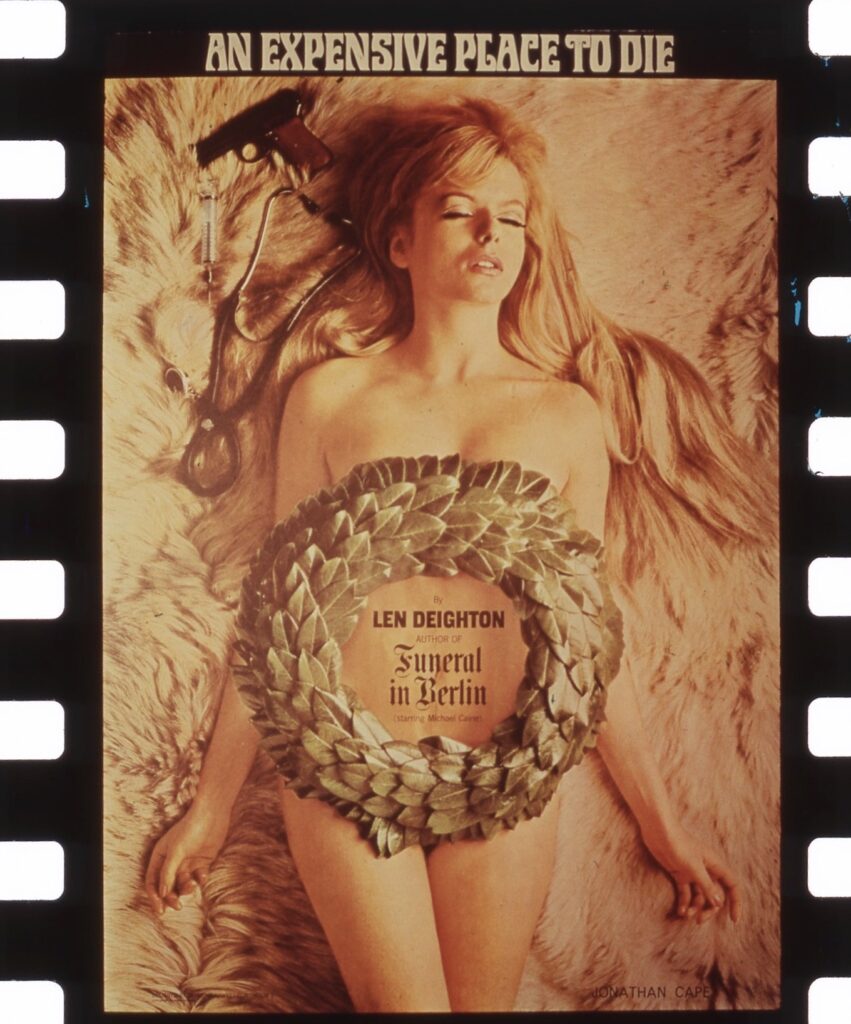

Following the success of his first spy thriller The Ipcress File, Deighton moved to Jonathan Cape, who in 1963 published his second novel, Horse Under Water. This was followed by Funeral in Berlin and three years later, The Billon Dollar Brain appeared, which, along with An Expensive Place to Die, published in 1967, confirmed his status as writer of gripping and complex stories, spy thrillers that were neither as melancholic as Le Carré’s, nor as simplistic as Fleming’s. In addition to the novels and cookbooks, he wrote non-fiction history books, mainly on WWII topics.

for the cover of Funeral in Berlin

However, even in his spy novels, food and cooking are a constant motif. In the opening pages of The Billion Dollar Brain, Alice runs up the stairs of the Charlotte Street offices with a tin of Nescafé, while the anonymous hero later has lunch in Trattoria Terrazza, enjoying ‘Tagliatelle alla carbonara, osso buco, coffee’ before being provided with a false passport that identifies him as one Liam Dempsey, born in Cork. In the first chapter of Funeral in Berlin, Hallam drinks his Darjeeling tea from an antique Meissen cup, and eats custard cream biscuits, while discussing the defection of a Soviet scientist. Later, in describing how to fry up breakfast, Deighton describes how the pan must cleaned with paper, not water, before cooking begins. However his self-description – ‘a supercilious anti-public-school technician’ wearing ‘mass-produced, off the peg clothes’ – is revealing. Much of Deighton’s success as a writer stemmed from these sharp barbs, in which few were spared. In Chapter 15, it may well be his friend Adrian Flowers who is referred to in a pub conversation:

A man with a paisley scarf tucked inside an open-necked shirt was saying, ‘He’s the best damn photographer in the country but he’s a thousand guineas a shot.’ A man with suede chukka boots said, ‘Our deep frozen fish-fingers nearly beat him. I said, “Make the beastly things out of plaster, old boy’ we’ll get the piping hot effect by burning incense.” We did too. Ha, ha! Put the sales up six and three-quarter per cent and he got some kind of Art Director’s award.’ He laughed a deep, manly laugh and sloshed down some beer.

In reality, Flowers prided himself on using real ingredients in his food photography, as in the above image of fish fingers, taken for Birds Eye. Although he had championed photography while a student at the Royal College of Art, Deighton in his novels sometimes seems to have had it in for photographers—part of the self-deprecating style that made his novels so attractive to readers tired of literary narcissism and improbable heroes.

In Chapter 18 of An Expensive Place to Die, the scene in Les Chiens bar—’hot, dark and squirming, like a can of live bait’—sums up something about Deighton’s attitude to both himself and the camera shutter. “On a staircase a wedge of people were embracing and laughing like advertising photos. At the bar a couple of English photographers were talking in cockney and an English writer was explaining James Bond.” A brawl then erupts when one of the photographers punches the writer, who is about to read a Baudelaire sonnet.

“There was a scuffle going on at the top of the staircase, and then violence travelled through the place like a flash flood. Everyone was punching everyone, girls were screaming and the music seemed to be even louder than before. A man hurried a girl along the corridor past me. ‘It’s those English that make the trouble,’ he complained.” When An Expensive Place to Die was ready for publishing, Hawkey produced a range of different cover designs, each of which incorporated photographs taken by Flowers.

Deighton married twice; the first time to fellow Royal College of Art student, the illustrator Shirley Thompson. Len and Shirley divorced in the mid 1970’s. Len’s second marriage, in February 1980, at Holte in the Netherlands, was to Ysabele, daughter of Johan Antoni and Frederika de Ranitz. A career diplomat, in the late 1940’s, Johan de Ranitz served as first secretary at the Netherlands Embassy in Sydney, Australia. Born in 1941 in the Netherlands, Ysabele is also is also the niece of WWII hero Eric Haselhof Roelfzema, whose autobiographical Soldier of Orange in 1977 was made into a Paul Verhoeven-directed film. Over the years she has assisted Deighton in translations and research. They have two sons, Frederick Alexander and Antoni. Over the years, Flowers photographed the Deighton family on several occasions, including visiting Len when he lived in Ireland, in the seaside village of Blackrock, Co. Louth.

Text: Peter Murray

Editor: Francesca Flowers

All images subject to copyright

Adrian Flowers Archive ©