Dump Circus, Nicola Hicks’s current exhibition at Flowers Gallery, is in many ways the culmination of a long and fruitful association, one that began in 1984 when she was chosen as ‘artist of the day’ at the Angela Flowers Gallery. The 2021 exhibition is a summing-up, not only of Hicks’s practice as a sculptor but also brings to the fore her darker and more dystopian view of the relationship between the world of humans and animals. Throughout the years of showing with the Gallery, her work was often photographed by Adrian Flowers, both as documentation of studio practice and for catalogue publications.

Born in London in 1960, Nicola Hicks grew up in a house surrounded by art and music. Her mother Jill Tweed, a graduate of the Slade School, is a celebrated portraitist and animal sculptor, while her father Philip Hicks, a painter who died in 2021, taught at the Harrow School of Art and was an accomplished jazz pianist. Hicks inherited her mother’s instinctive affinity with animals—as a child she moulded images in clay in Tweed’s studio—and also her father’s humanitarian spirit: his 1969 Vietnam Requiem is a moving homage to those who suffered in that war. From the outset, animals played an important role in Hicks’s life; dogs were always a part of the household and her mother drew and sculpted sheep, dogs and horses. In 1978, aged eighteen, Hicks enrolled at the Chelsea School of Art, graduating four years later and continuing on to post-graduate studies at the Royal College of Art. In 1984, Elisabeth Frink chose the then twenty-four year old as ‘artist of the day’ at the Angela Flowers Gallery and the following year, Hicks had her first solo show, entitled No Ordinary Beasts, at Flowers. She enjoyed immediate success, exhibiting also at the Hayward Annual, Kettles Yard and the Serpentine Gallery. Works from this period include Hush and I Blow out the Flame (Dancing Girl) a sculpture depicting a pig, and the plaster and straw Death Comes a-Creeping, depicting perhaps an act of coitus, or the death of an animal. Brown Dog*, dating also from 1985, is cast in bronze and sited at Battersea Park. From the outset it was clear that while some of animals depicted by Hicks may be domesticated, in her art their wild nature is emphasised, their primal nature coming to the fore. Her work contains complex references, both visual, literary and metaphorical and her ‘hands on’ approach, while evoking Modernist and contemporary art practice, also references Palaeolithic paintings, where images were created by rubbing soot and ochre pigments onto the walls of caves; the oldest art works known to mankind. Her creatures seem often extracted from a primal sub-conscious sense of the world, evoking simultaneously both life and death.

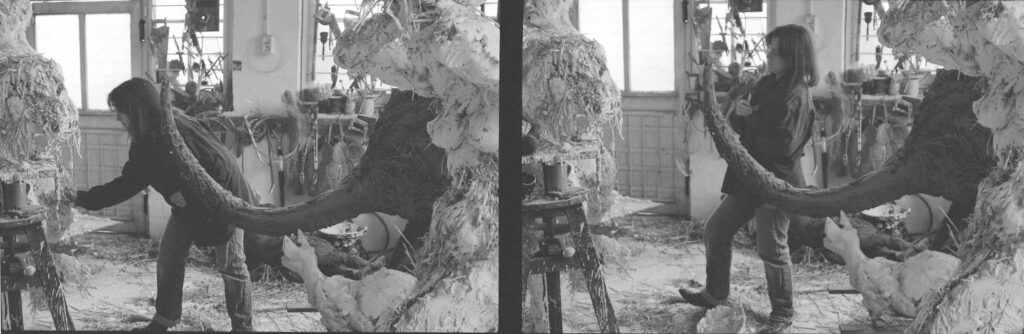

In 1986, along with a series of large-scale drawings, Hicks’ site-specific sculpture The Fields of Akeldama was installed at the Angela Flowers Gallery at Rosscarbery in West Cork, Ireland. The title of this work refers to Akeldama, the ‘Field of Blood’, the valley near Jerusalem traditionally identified as the place where Judas Iscariot died. Hicks carved the forms of animals out of the living clay, mixed with straw; these outdoor works were eventually eroded by rain, returning into the ground from which they had been sculpted. In 1986 too, Hicks created earth works at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park. During those years, her dogs—Brock, a Jack Russell and a greyhound named Rocket (rescued from the Battersea Dogs Home)—featured in her work, notably in the sculpture Rocket 6-1, shown at the Chicago Exposition in 1987, and in her 1989 show at Flowers East. She travelled to India in 1987 with the Henry Moore Memorial Exhibition, a journey that resulted in a new series of works, in which elephants and lions made their appearance. While she has showed at the Beaux Arts Gallery in Bath, and other venues, her principal affiliation has always been to Flowers Gallery, where she has exhibited regularly up to the present day. Works shown in 1989 include Shudder in the Citadel**, a tusked elephant of plaster and straw, wrapping its trunk around its foot, the handwrought surface still bearing the marks of the artist’s hands.

In 1988 Hicks represented Britain at the Rodin Memorial Exhibition in Japan, and the following year travelled in Australia, drawing and sculpting that continent’s flora and fauna, including tortoises and kangaroos. These works were shown in her 1991 Flowers exhibition entitled Fire and Brimstone, characterised by the translation of straw and plaster sculptures into bronze. The following year she exhibited drawings and sculptures inspired by Bill, her new-born son. A 1994 bronze sculpture of a cow falling, Cow Says Moo, was donated by Barbara Lloyd to Murray Edwards College in Cambridge. Other public commissions followed: the monumental bronze Beetle (2000) is sited at Anchor Square in Bristol, near Pero’s Bridge, while her equestrian sculpture of a mounted knight atop a column, also from 2000, is in the Inner Temple courtyard, London. In 1995 an exhibition of her work was held at the Djanogly Art Gallery in Nottingham, and also at Flowers East, featuring works that contained more than a trace of self-portraiture, such as Mother of Minotaurs, Bull Woman, My Love My Heart and Me—works that marked her own giving birth and her maternal relationship with her child.

That same year, she was awarded an MBE for her services to the visual arts. Through these years, the complexities and nuances in Hick’s work continued to develop: In the sculpture Dan’s Story (2003)— as in a Renaissance painting—cherubs, or putti climb onto a lion’s back, cavorting and gamboling, sitting on the animal’s head grabbing its mane and pulling its long tail. But the darker side of Hicks’s sculpture is never far from the surface. With Banker II (2009) she created a ghoulish horned human figure, walking, carrying perhaps the remains of carcases in its hands. In Hypocrites (2011) a sad bear stands over a dog. The bear seems oblivious to the dog’s rolling over on its back. At Schoenthal, her Crouching Minotaur (2013) is sited in a field.

Hicks identifies so closely with animals that they seem to enter and possess her consciousness. Initially, her sculptures and drawings of animals concentrated on anatomy and movement, but in more recent years, the tone has become more dystopian, exploring the often-fraught relationship between animals and people. Affirming that her approach is intuitive and instinctive, rather than intellectual, she is not afraid to scrap a piece if she feels it is not going well. “The beauty of beasts is in their movement, and their expression. You don’t get much expression out of something when it’s rigid. When I start to make a piece of sculpture, it’s very often like – you almost want to dance, you almost want to get yourself into the pose, and you think – I’m making a cat, . . balancing very gently on something, that’s also balancing very gently, and it’s a delicate relationship that’s building up. Now how does that cat have to be, to balance – where is the tail going to be? And that’s where the movement comes in.”

In 2013 Hicks showed at the Venice Biennale and also had a one person-show at the Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, Connecticut. Among the sculptures shown at Yale was Who was I Kidding (2013) where she adapted the story of the donkey from Aesop’s Fables. In this tale, a donkey wearing a lion skin and terrifying other donkeys, is unmasked by his own braying, and so becomes the subject of ridicule. The materials used, plaster and straw, add to the sense of the abject. There not an ounce of sentimentality in Hicks’s art, which is often brutally direct. She is acutely conscious of the tendency to identify traits in animals that resemble or echo human emotions. Termed the “pathetic fallacy” by John Ruskin in his 1856 Modern Painters, this is a point of view from which animals are seen, incorrectly, as exhibiting human emotions. Hicks is unambiguous on this point: “Animals are not cute and cuddly. From a distance perhaps, without your specs. As soon as you get close up, it’s a beast. It’s an animal, it’s surviving. . . We’re just another species. We think we’re so different and we’re not. I make sculpture for pure and emotional reasons. I didn’t choose to be a figurative sculptor. For me to be an abstract sculptor it would be pretending. That’s not how I work. That’s not how I think.” Not infrequently, the animals she depicts seem to be hurt or in pain. Nonetheless, her drawings bring them to life on the page, resonating with vitality and a sense of movement. While her subject-matter belongs within the realm of Bernini, the Baroque, Landseer, classic chapters in the history of Western Art, her approach is unique, personal and of our times. In placing a cat-like creature on top of an upturned tortoise, there is a gentle allusion to Polynesian creation myths, in which creation stands on the back of a tortoise. Having lived in Australia, tales of how the world originated would have been part of the culture she encountered. She blends these elements together to create works that resonate with a visceral visual and tactile strength, transcending time and place, and forcing the viewer to reappraise where the human race stands in relation to the natural world.

Hick’s work has been written about and reviewed extensively; by Mary Rose Beaumont in Arts Review (Sept 1988 and January 1991) and Brian Sewell in Evening Standard (Dec 1988). Robert Heller contributed an essay to the 1989 Flowers Gallery catalogue, as did William Packer. Giles Auty wrote about her work in The Field in November 1992, and William Packer in the Financial Times (18 July 1995) Tom Phillips contributed an introduction to her 1991 catalogue Fire and Brimstone. In 1998, Will Self wrote a catalogue essay for her show The Camel that Broke the Straw’s Back. The following year, on May 25, her work was reviewed by Frances Spalding in The Independent. In 2000 Tobey Crockett reviewed Hicks’s work in the January edition of Art in America.

*https://artuk.org/discover/stories/nicola-hicks-brown-dog

**Shudder in the Citadel featured in the South Bank Show:

Text: Peter Murray

Editor: Francesca Flowers

All images subject to copyright.

Adrian Flowers Archive ©