12 May 1921 – 23 January 1986

In February 1972, Joseph Beuys, by then something of a star in the international art world, visited London to perform Information Action at the Tate and Whitechapel galleries. The work consisted of a lecture and discussion, with Beuys drawing diagrams and cryptic notes on a series of blackboards, a technique that had become his signature trademark. This was far from being his first visit to the UK; two years previously Beuys had collaborated with Richard de Marco on a series of projects in Scotland. He also worked extensively with writer and curator Caroline Tisdall. The three blackboards resulting from the 1972 London event remained for over a decade in the store of the Tate education department, until in 1983, along with a board from a parallel event at the Whitechapel Gallery, they were accessioned into the Tate collection as artworks in their own right. Although in some respects souvenirs, the boards with their chalked diagrams still convey the excitement of the lectures, which were animated by the charismatic personality of Beuys himself.

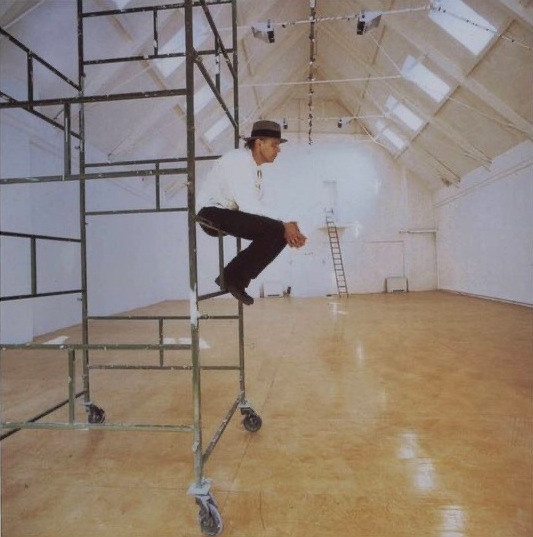

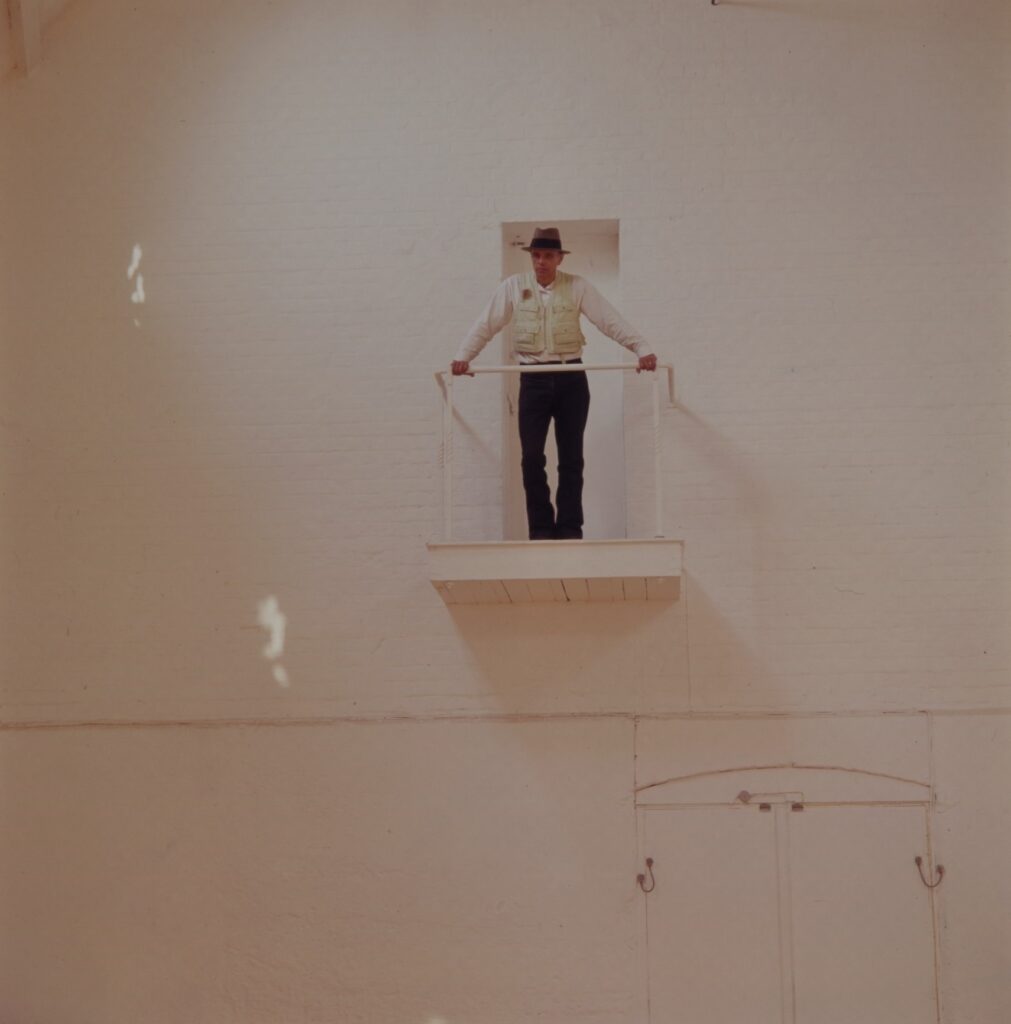

A series of photographs, taken by Adrian Flowers at the Whitechapel Gallery in Feb 1972, show Beuys with his characteristic gaunt expression, wearing a grey felt hat with black hatband. His face is lopsided, perhaps as a consequence of injuries received when he served in the German military during WWII. With its armband and brass buttons with crosses, the artist’s coat is also provocative, the red gorget patches on the lapels reminiscent of a military officer. Underneath the coat is visible the fisherman’s vest Beuys invariably wore. Another photograph shows the artist standing on a small balcony, high above the gallery floor, in a pose that again has historical resonances. A third image shows Beuys sitting on the bar of a scaffolding tower. The available props in the Whitechapel gallery space, ladders, towers and steeply raked rooflights, were used effectively, with Beuys becoming an actor in an expressionist stage set.

At the time of the Tate/Whitechapel event Beuys was head of sculpture at the Dusseldorf Academy, but his unorthodox teaching methods were becoming increasingly controversial, and in October of that year, notwithstanding protests amongst artists and students, he was dismissed. If anything, this increased his fame and, through association with movements such as Fluxus, over the following decade he enjoyed a successful international career, culminating in a retrospective at the Guggenheim in 1979. Seven years later, shortly after winning the Wilhelm Lehmbruck Prize, Beuys died aged 64. Over the decades following, while much of the mystique that had propelled him to the forefront of the international art scene began to ebb, his life, legacy and philosophies continued to fascinate biographers and critics, often eager to tear aside the veil of veneration with which this charismatic artist was regarded by his followers. He certainly mythologised his own life, creating fictional biographical details—such as his having been a Luftwaffe pilot, shot down in the Crimea, and rescued by local nomadic Tartars, who wrapped him in felt and carried him on a sled to a place of safety. These life episodes, heavily embellished rather than invented, were used by Beuys to explain and underpin the meaning of his artworks, especially his sculptures which often incorporated sleds, fur, fat and felt.

As a teenager, Beuys had been a member of the Hitler Youth, had participated in the 1933 Nuremburg Rally, and later served as a radio operator in the Luftwaffe. His plane was indeed shot down in the Crimea, but he was rescued by German troops and saw further military service before the end of the war. In the post-war years, his art was largely based on a simultaneous reverence and revulsion regarding these aspects of his life. Often, albeit without any trace of humour, he brings to mind the fictional character Schwejk, an anti-hero who forms relationships with animals, and finds himself in absurdist situations. In essence however, Beuys’ ideas were not so innovative or revolutionary, but were based on the writings of Nietzsche and Rudolf Steiner, and on the training he received in the late 1940’s under Ewald Mataré at the Dusseldorf Academy.

Beuys was an idealist, arguing for a spiritual rebirth for mankind, based on qualities of essential humanity. Drawing on shamanistic traditions, he regarded art, or what he called ‘social sculpture’, as a liberating force that could enact social change. He was often deliberately controversial in his lectures and pronouncements, comparing the suppressing of creativity in people—a consequence of industrialisation—as akin to the extermination policies of the Nazis. An ardent admirer of James Joyce, in the late 1950’s Beuys began work on a series of drawings inspired by the novel Ulysses. At one point, encouraged by the art critic Dorothy Walker, he considered setting up a free university in the Wicklow mountains, near Dublin. His assemblage of works, A Secret Block for a Secret Person in Ireland, is in the Museum of Modern Art at Oxford. He was also a frequent visitor to Scotland, where he collaborated with Richard de Marco on projects relating to Celtic history and legend, that formed part of the Edinburgh Festival. Beuys’s work in the UK and Ireland has been documented by his friend Caroline Tisdall, later art critic for The Guardian, who has also organised exhibitions and published several books on the artist.

Text: Peter Murray

Editor: Francesca Flowers

All images subject to copyright

Adrian Flowers Archive ©