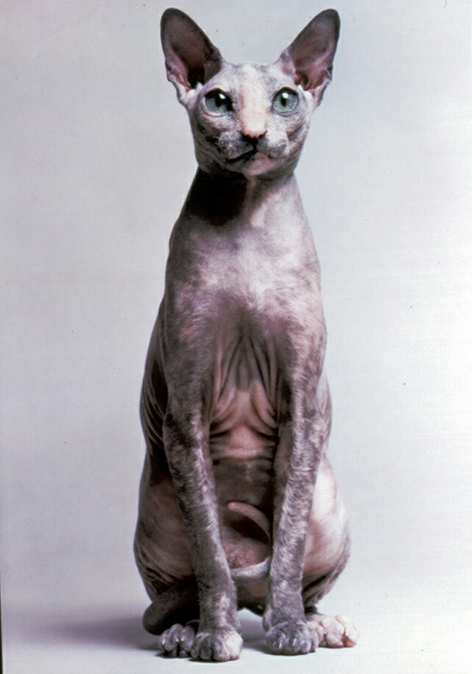

Beginning in 1967, Adrian Flowers received the first of many commissions to photograph covers for the Observer magazine. For journalist Hilda Hunter, a specialist on rare animals, he provided suitably regal images of a Rex cat, while for an feature by Maureen Green, marking the anniversary of women getting the vote, he photographed a group of veteran Suffragette campaigners, standing with banners for ‘Womens Freedom League’ and ‘National Union of Womens Suffrage Societies’. The veterans included Stella Newsome, Grace Roe, Lady Winstead, Beryl Bower, Mrs. Duval (Una Dugdale), Dame Kathleen Courtney, Jessie Kenny and Mary Stocks. During the shoot, Adrian’s assistant Bob Cramp recalled the women swapping stories of how they had flouted the law in their youth.

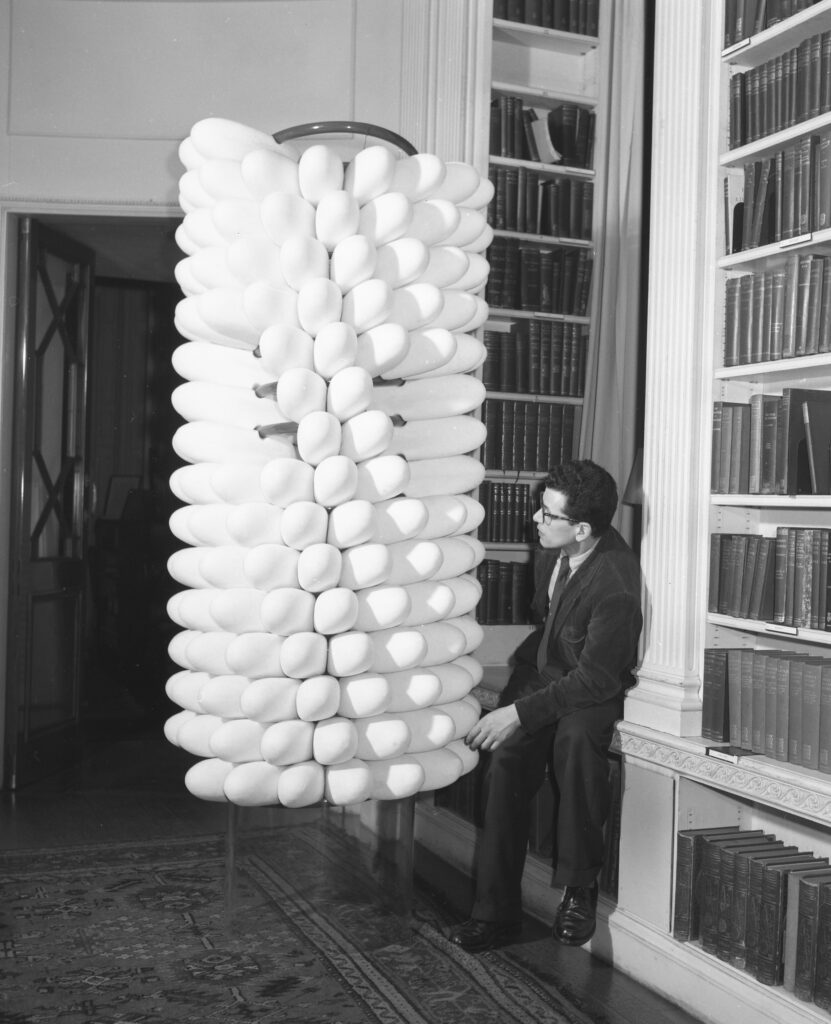

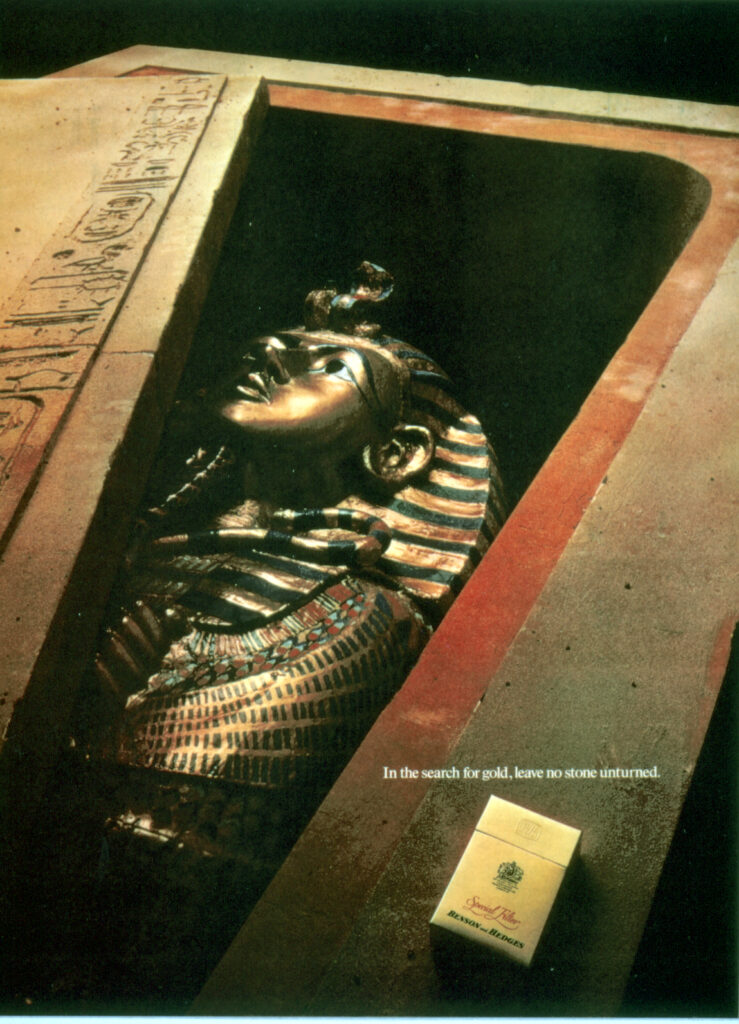

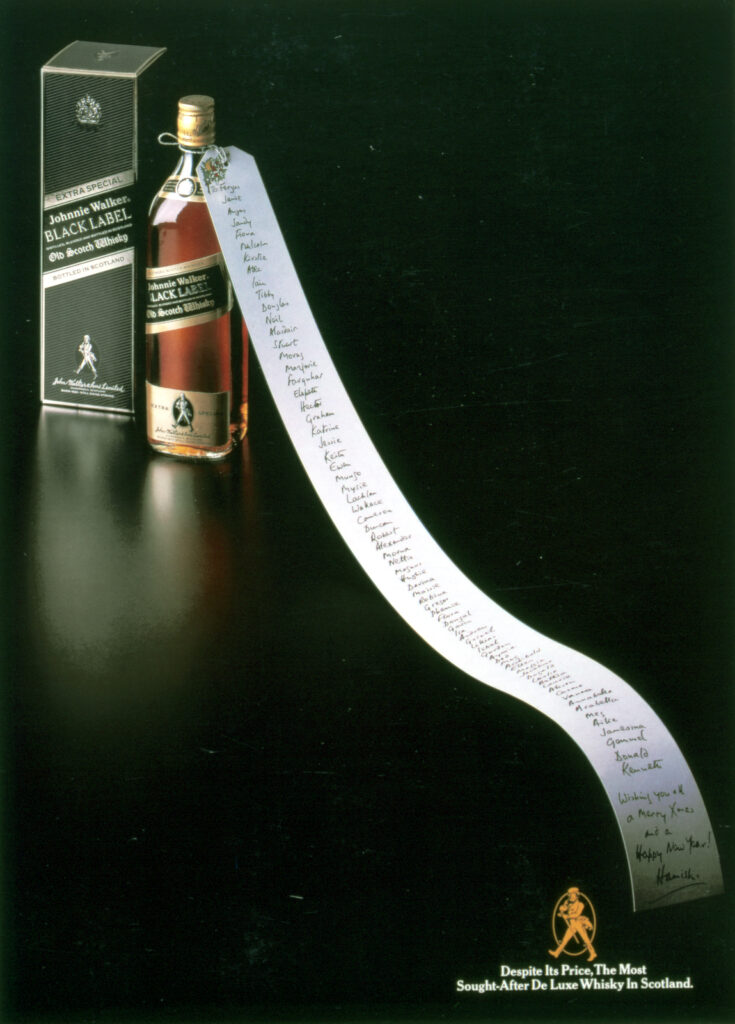

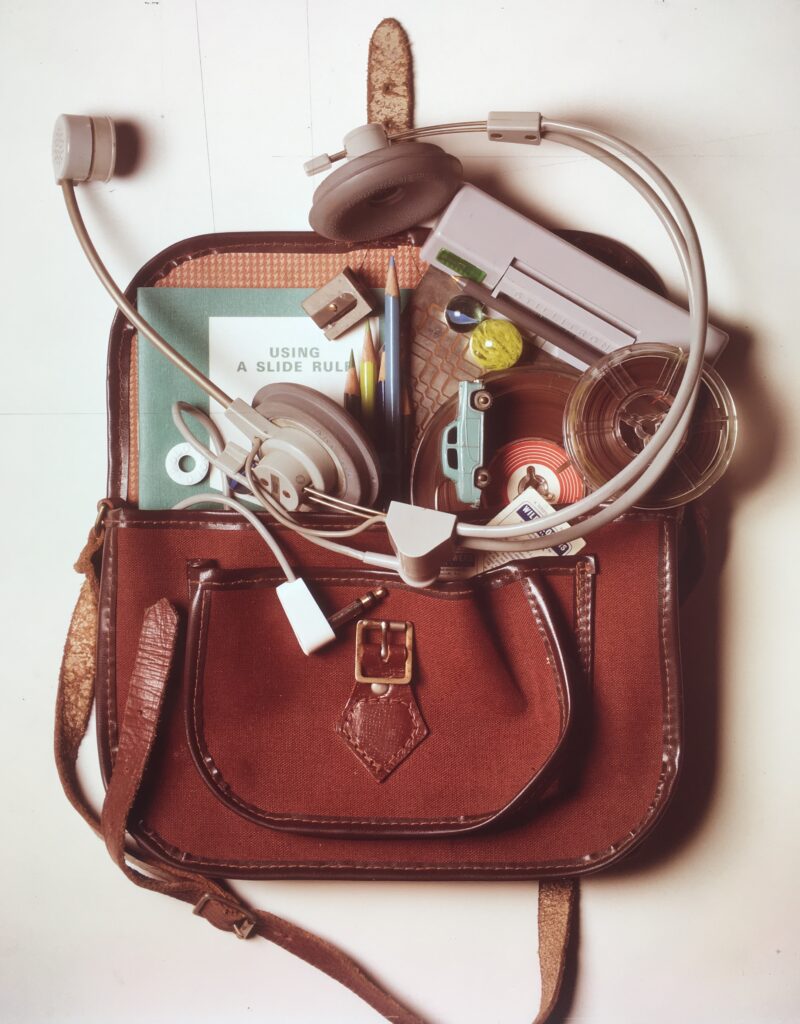

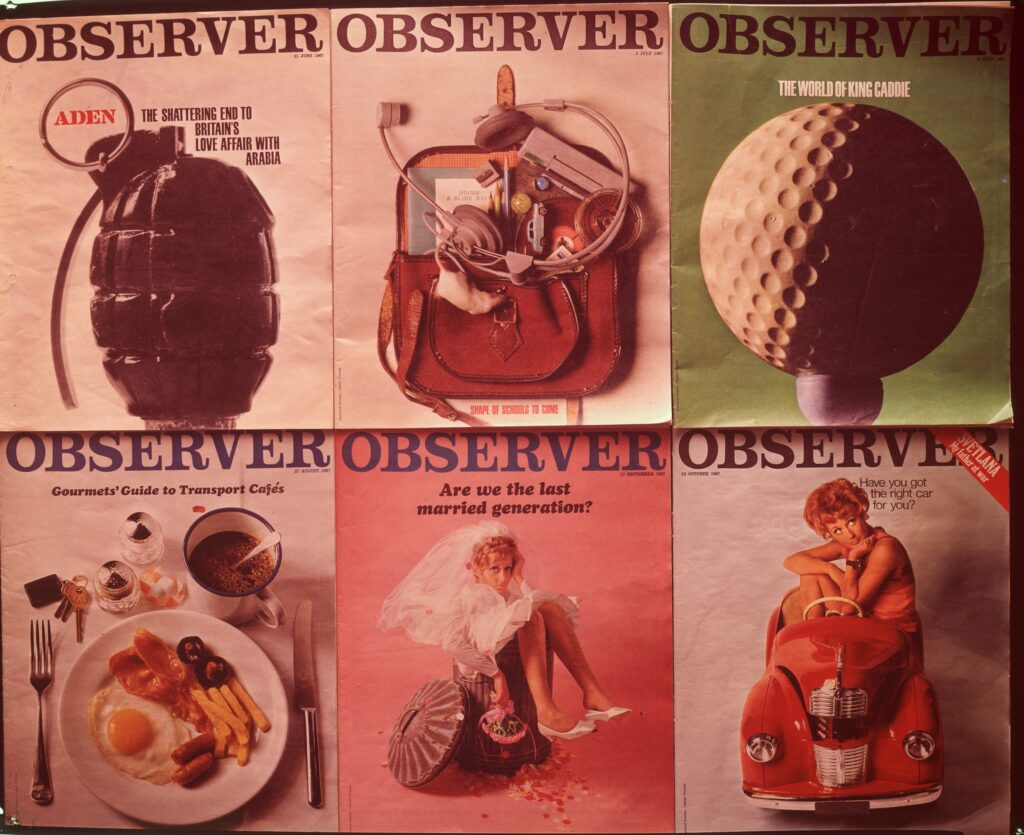

Most of the Observer commissions came to Adrian via Raymond Hawkey, who had been appointed head graphic designer at the newspaper the previous year. Renowned for his use of bold graphic images and san serif fonts, Hawkey is perhaps best-remembered for his series of memorable covers for the 1960’s Pan paperback series of James Bond novels. The Observer commissions he brought to Adrian were wide-ranging. A close-up of a hand grenade dominated the magazine’s front cover for 11 June 1967: “Aden: the shattering end of Britain’s love affair with Arabia”. For a feature on ‘the shape of schools to come’ (2 July 1967) Adrian photographed a school satchel, containing magnetic tapes, a Stillitron and other futuristic learning aids, alongside conventional pencils and paper. Partly hidden behind a headphone set, a ‘Wild Flowers’ cigarette card provided a classic Adrian Flowers signature touch. The following week’s cover featured a close-up of a golf ball, for ‘The World of King Caddie’, while a breakfast fry-up, with coffee in an enamel mug, provided an apt image, on 27 August, for ‘Gourmets’ Guide to Transport Cafés’. On 17 September, a disconsolate bride in a dustbin, veiled and still holding her bouquet, was an arresting, and Beckettian, image for ‘Are we the last married generation?’. These images captured the essence of Britain’s fast-rising middle class, who shared disenchantment with a colonial past, fascination with new technology, and who welcomed the blurring of social identities.

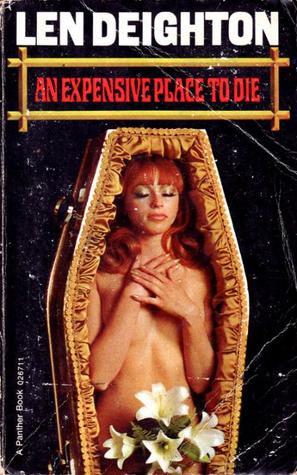

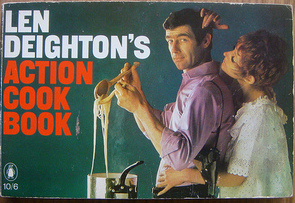

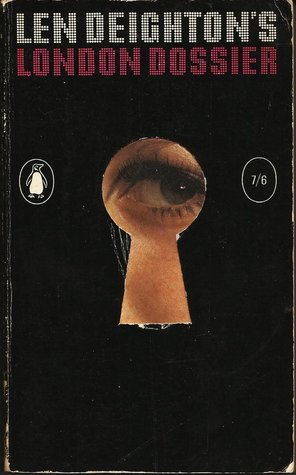

Hawkey created a visual language that expressed the tenor of an age, one in which confidence and insecurity vied for dominance. Influenced by American designers and photographers such as Saul Bass, Herb Lubalin, Alexander Liberman, Irving Penn and Richard Avedon, his own career reflected these shifts in society; after a childhood in Cornwall, he attended art college in Plymouth, winning a scholarship to the Royal College of Art. At the RCA, along with Len Deighton, he was art editor for Ark, the college magazine, causing a minor scandal by featuring a nude photograph on the front cover—photography was disapproved of at the Royal College. Adrian Flowers was also a friend of Deighton, having met him in 1947 while both trained as photographers with the RAF. Following success in a competition run by Vogue magazine, Hawkey worked for its publishers, Condé Nast, for several years. He then moved on to the Daily Express, before becoming head designer at the Observer, where he revitalised the colour magazine that came with the newspaper. The easing up of newsprint rationing in the late 1950’s enabled newspapers to expand and develop, and the Observer caught the spirit of the times. Although he was nattily-dressed, soft spoken and invariably polite, Hawkey’s imagery could be shocking and at times disturbing. Len Deighton asked him to design front covers for his novels, including The Ipcress File, with Adrian providing images for Hawkey to use in designs for several of these novels.

Deighton Dossier includes a chapter on Photography written by Adrian Flowers

www.deightondossier.net

https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2020/apr/12/from-the-observer-archive-morecambe-and-wise-kenneth-tynan

https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2019/dec/29/from-the-archive-britains-national-traffic-jam-in-1971

https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2019/oct/13/from-the-archive-1967-western-journalist-under-arrest-in-china-for-777-days

https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/series/from-the-observer-archive

Image of the Suffragettes was used in Diane Atkinson’s 2018 book Rise up, Women! The Remarkable Lives of the Suffragettes. www.dianeatkinson.co.uk

Text: Peter Murray

Editor: Francesca Flowers

All images subject to copyright.

Adrian Flowers Archive ©