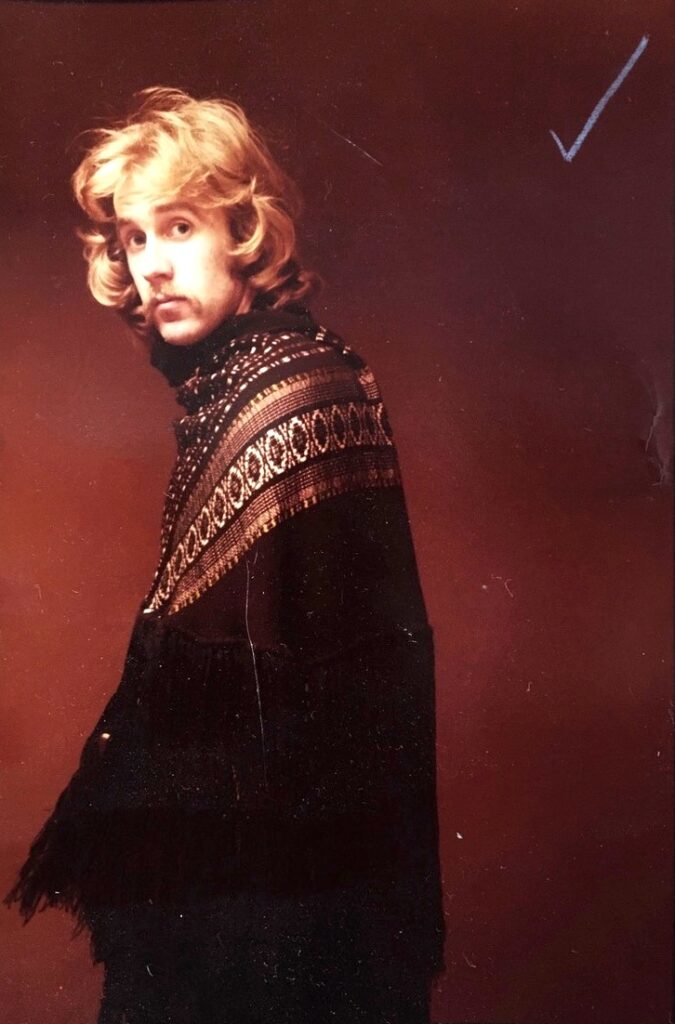

Meeting with Steve Garforth, who settled in France in 2014, provides a unique insight into the work of the Adrian Flowers studio in the early 1970s. During those years, the studio was housed in ‘The Tower House’, at No. 46 Tite Street, Chelsea. Although Garforth was employed as a first assistant photographer, in this photograph, taken around 1973, he had volunteered to stand in for a lighting ‘set up’. The photograph shows him wearing an exotic shawl, the work of a textile designer [name unknown] who had a studio next door. In 1972, having seen Flowers’ exhibition In the Round at the Angela Flowers Gallery, Garforth, a Yorkshireman, was inspired to become a professional photographer.

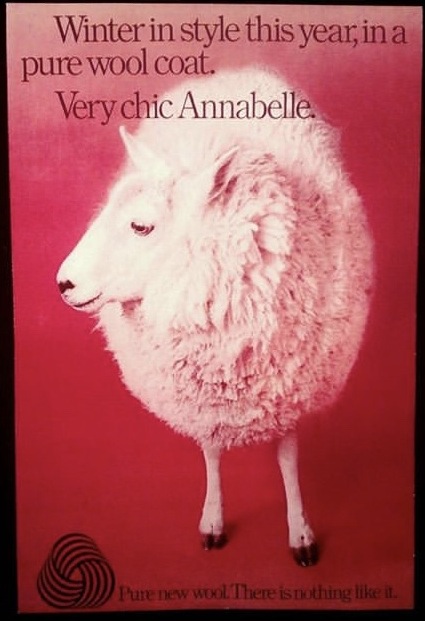

He applied for a position at the studio, and after several interviews, and a good deal of perseverance, was taken on as an assistant. These were heady years, when commissions flowed in from top magazines and advertising agencies. Garforth describes Flowers as ‘an innovator and a problem solver’. Agencies would come with ideas; the studio team would assemble for a detailed briefing and brainstorming session, a strategy would be agreed and a presentation prepared. The agencies were invariably impressed. For one campaign, for the Wool Board’s ‘Wool Mark’, Garforth recalls they constructed a black-out studio in a field, in order to photograph sheep, including a prize ram named ‘James’.

Other campaigns, for companies such as Young & Rubicam, included cigarette brands Silk Cut and Benson & Hedges. They also did work for Caravans International, covers for the Observer magazine, and many shoots with Arthur Parsons. Garforth remembers the team at the Tower House; the vivacious Gala Pinion, studio secretary, Kathy Vibert, Tor Hildyard, and assistant photographers such as Tony McGee, who did not last long at Tite Street but went on to surprise everyone by becoming a famous Vogue photographer. The studio printer at Tite Street was Tony. Garforth, who worked as first assistant photographer, recalls Flowers’ love of music, primarily jazz—Charlie Parker, Stan Getz and Miles Davis— but also his occasional forays into Stockhausen, music which was not so popular with the studio team. He also recalls Flowers’ tendency to file material, rather than dispose of it, a tendency that led to the growth of the AF Archive into a substantial entity. Initially, the Archive was housed in a number of garages in Clapham, before being moved to France—and, more recently, to West Cork.

In 1976, Garforth, having gained experience with complex technical assignments, and learned something of Flowers’ love of the surreal, was the photographer for Curved Air’s album Airborne, and the following year he was responsible for Steeleye Span’s Original Masters. Moving on to establish his own independent career, for over two decades Garforth specialised in photographing cars, work that took him around the world. Along with this, his exquisite still lifes and portrait work remain an important part of his oeuvre. In the first decade of the century, Garforth and his wife Bea restored San Bartomeo de Torres, a medieval priory near Girona.

Even after a span of forty years, Garforth remembers Flowers with fondness: “Adrian could be exacting, never suffered fools and would explain the simplest thing in the most eloquent manner, but he was kind, thoughtful and generous to all who worked with him. If you graduated from Adrian’s studio you were guaranteed a good career and we all owe him so much for that. . . When we moved to France in 2014 I wanted to help Adrian take pictures again. He had so many wonderful still lifes set up around the barn, but when I asked him had he taken pictures of them, he simply replied “these days only with my eyes” “

Text: Peter Murray

Editor: Francesca Flowers

All images subject to copyright.

Adrian Flowers Archive ©