1912 – 2004

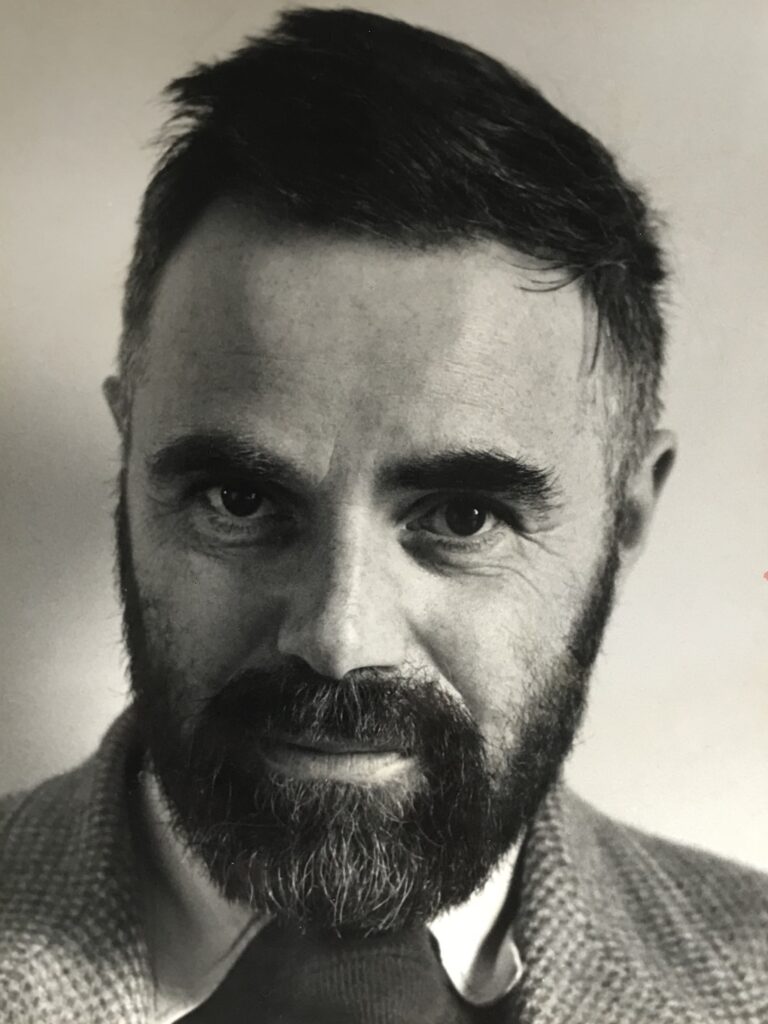

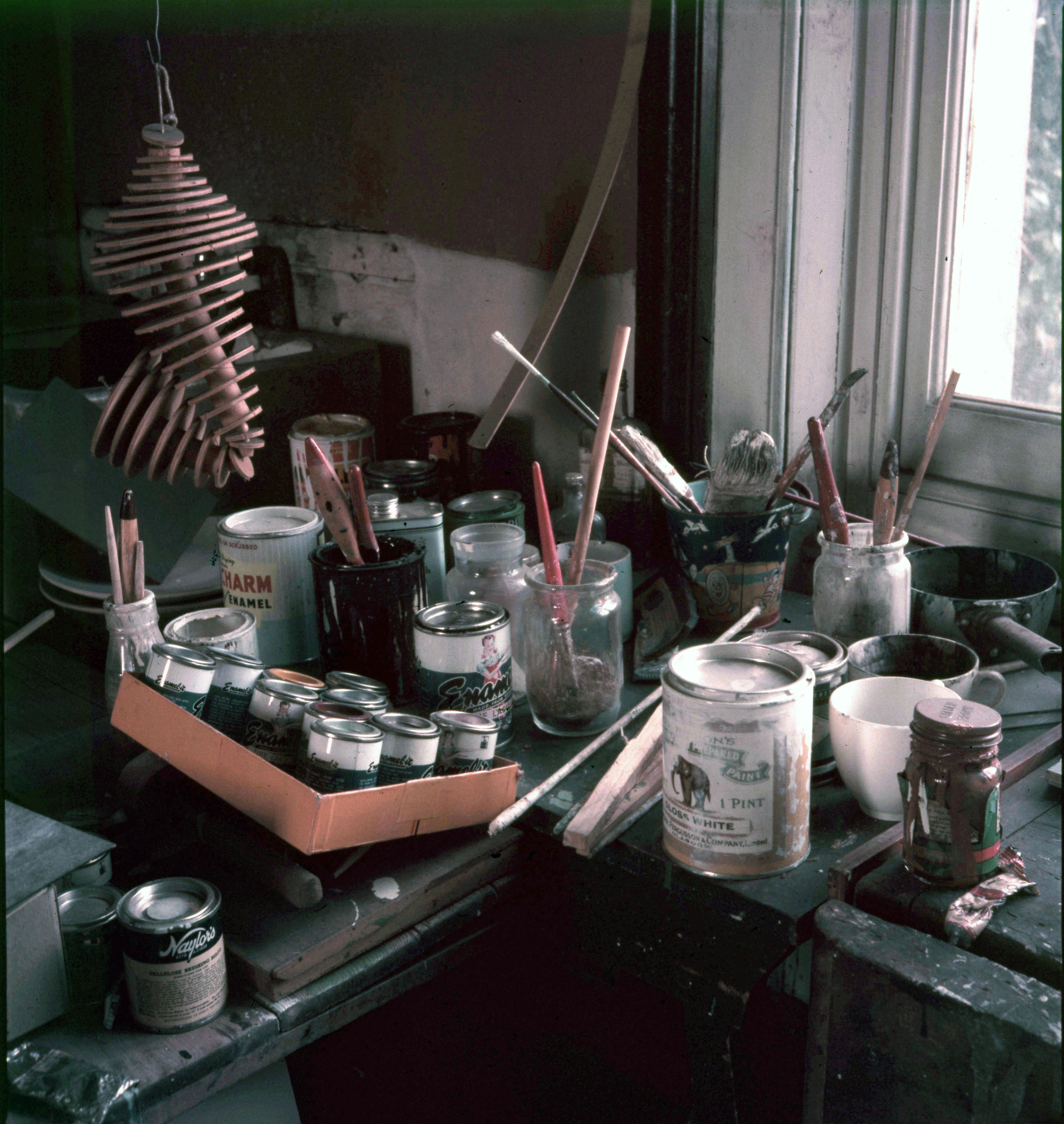

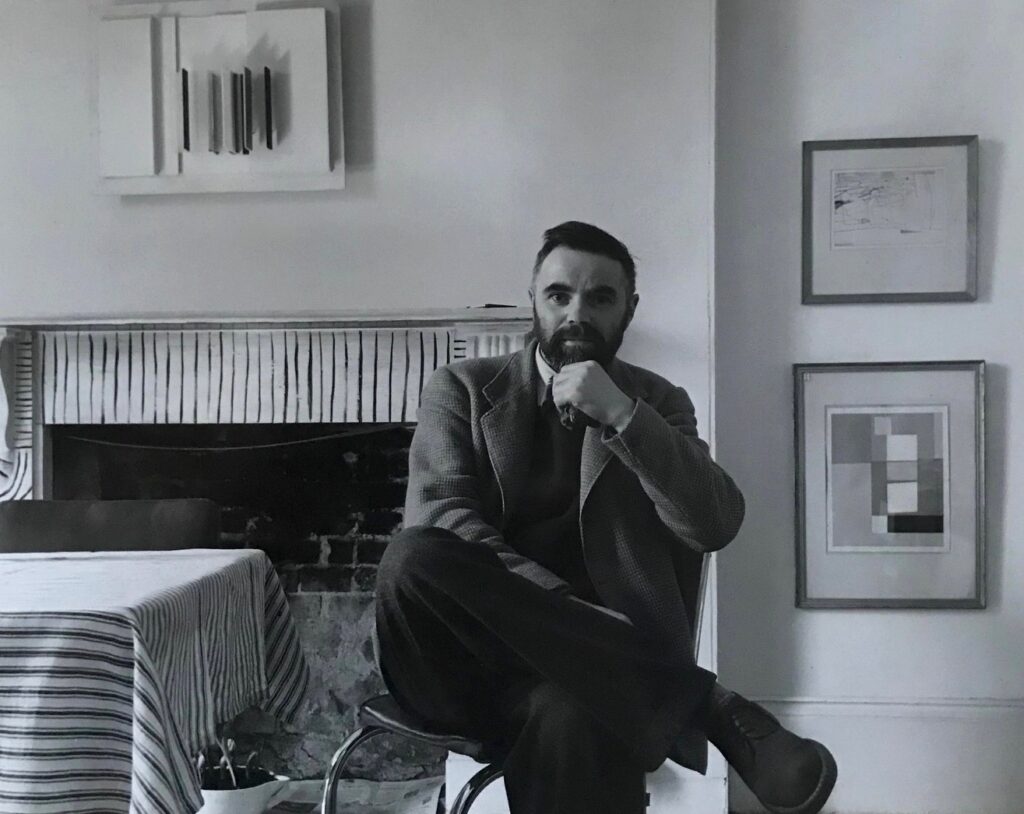

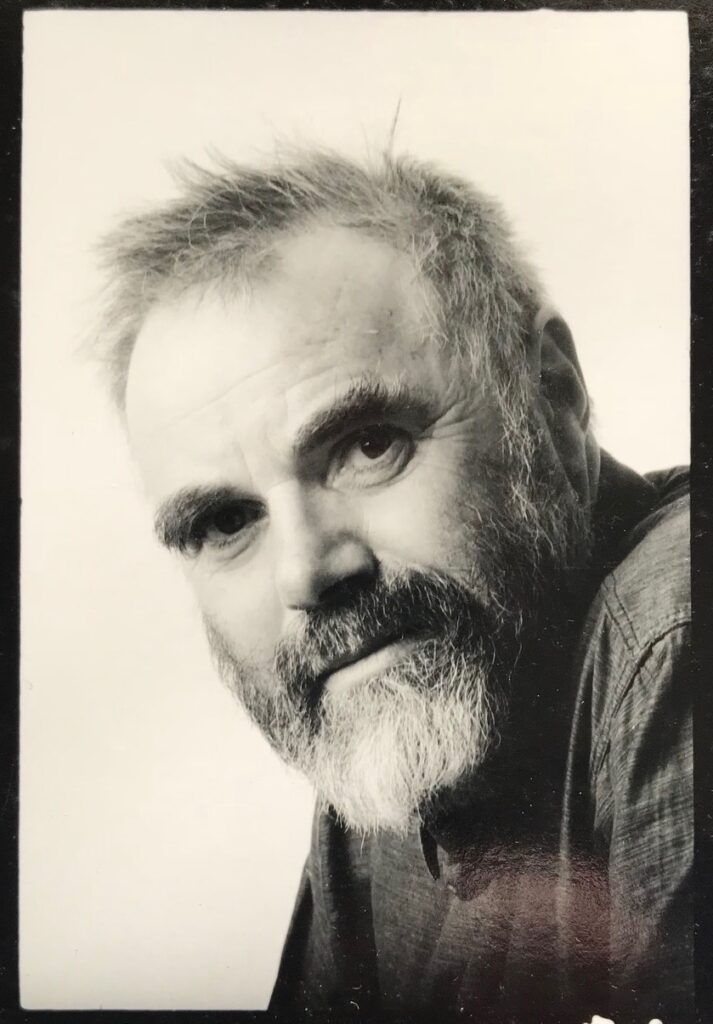

With the publication of Virginia Button’s recent book on Wilhelmina Barns-Graham, following on Lynne Green’s monograph W. Barns-Graham, A Studio Life, the achievements of this leading post-war abstract artist are now being fully recognised. Although a key member of the St. Ives group, Barns-Graham was unfairly marginalised in the 1985 survey exhibition ‘St. Ives 1939-64: Twenty-five years of Painting, Sculpture and Pottery’, held at Tate St. Ives—although two subsequent solo exhibitions of her work at that museum have gone some way towards remedying the oversight. In some ways, as Button points out, in refusing to remain silent on the issue of gender discrimination, Barns-Graham found herself alienated from the largely male cadre of curators, artists and patrons of the period, who felt she was not ‘playing the game’. The frontispiece in Button’s book, a photograph portrait taken by Adrian Flowers in 1955, shows the artist in her studio. During his visit, Flowers also took photographs of her paintings, sculptures and geometric plaster reliefs.

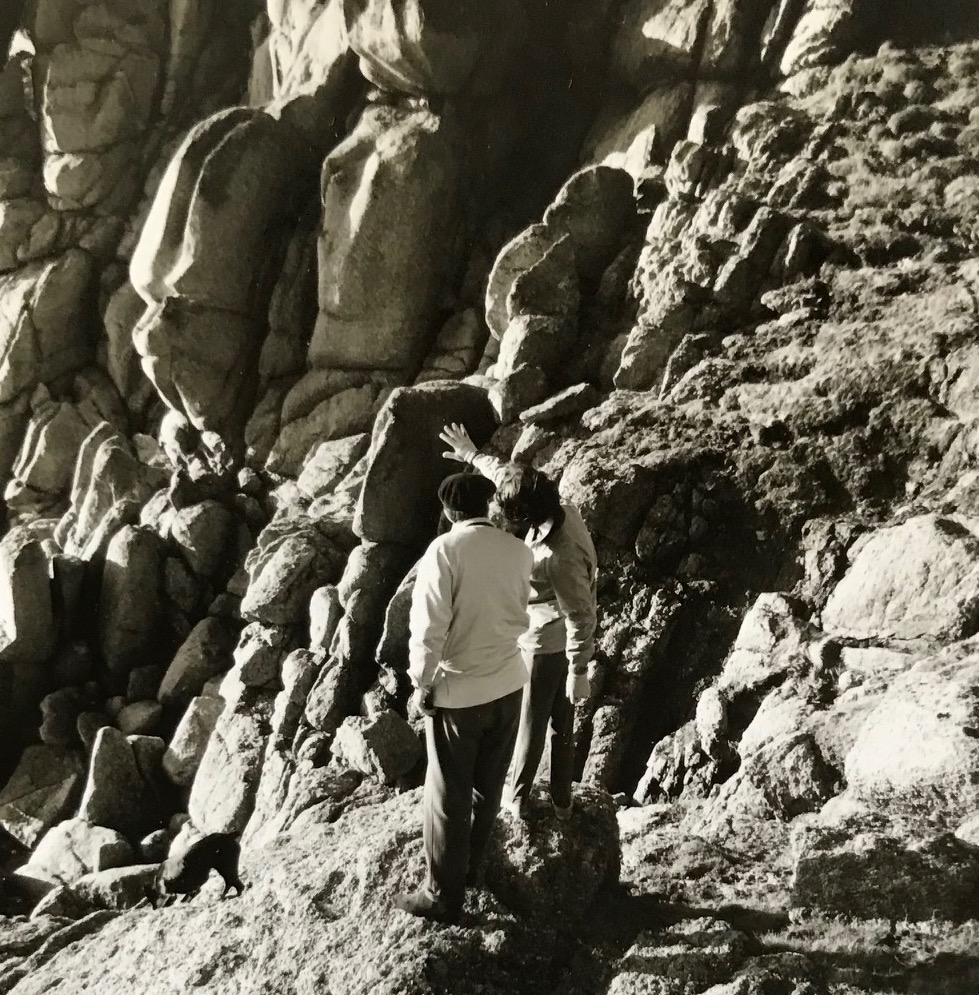

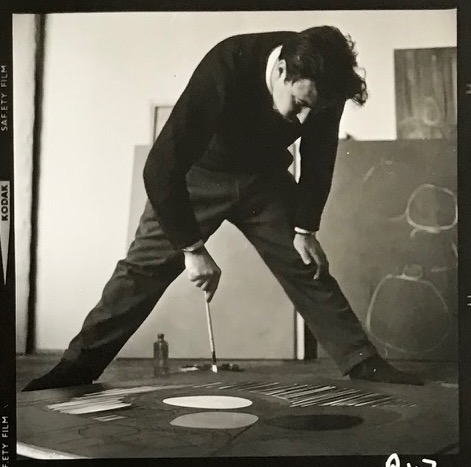

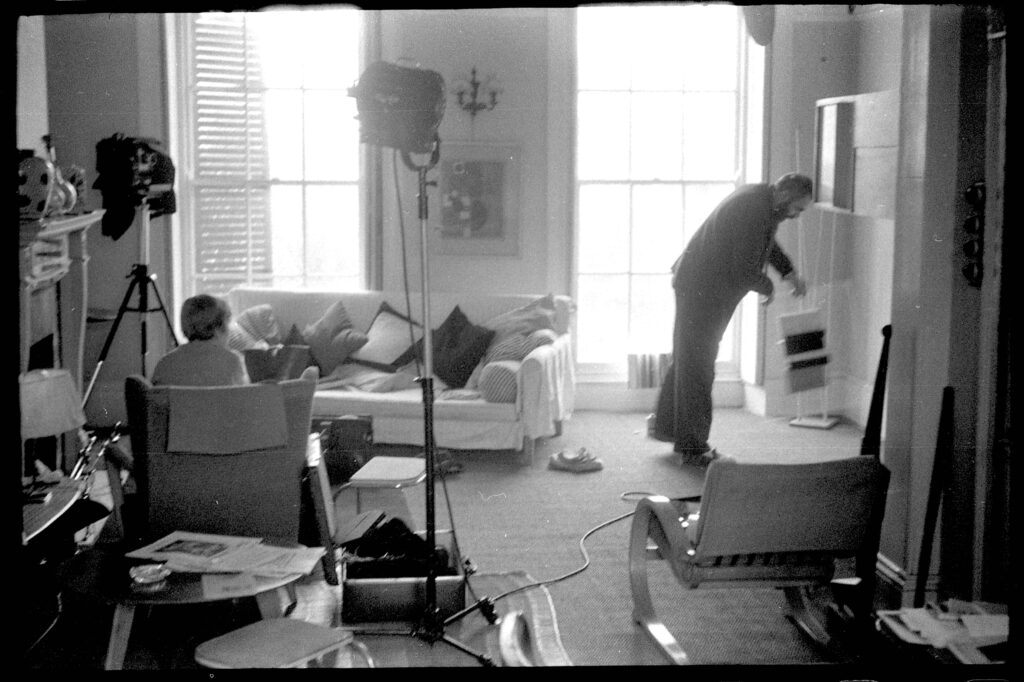

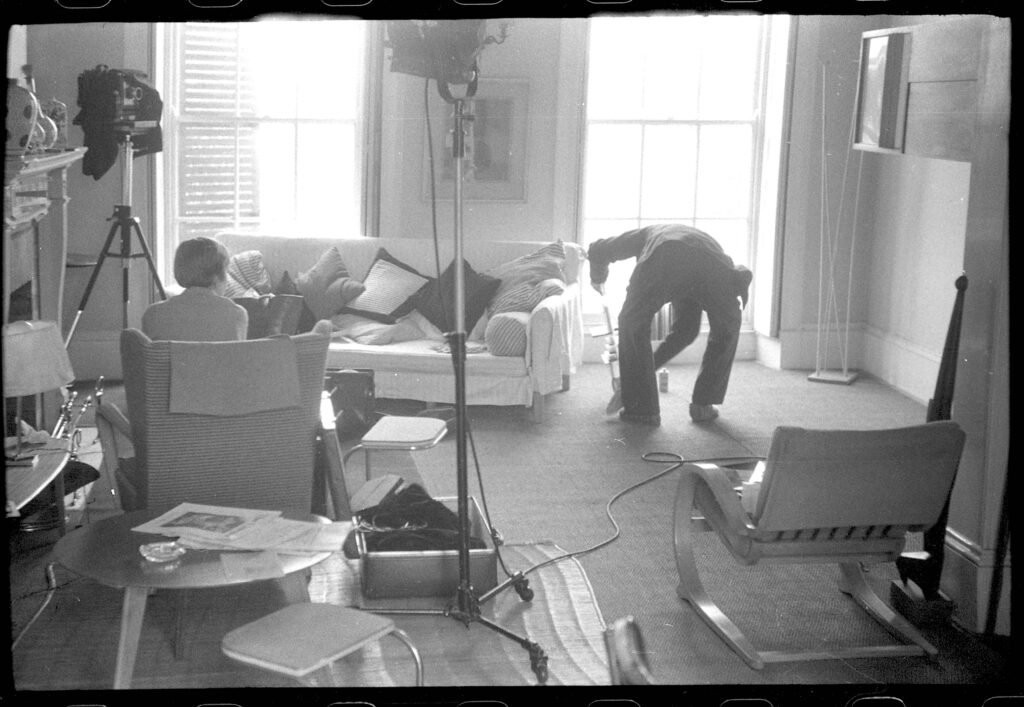

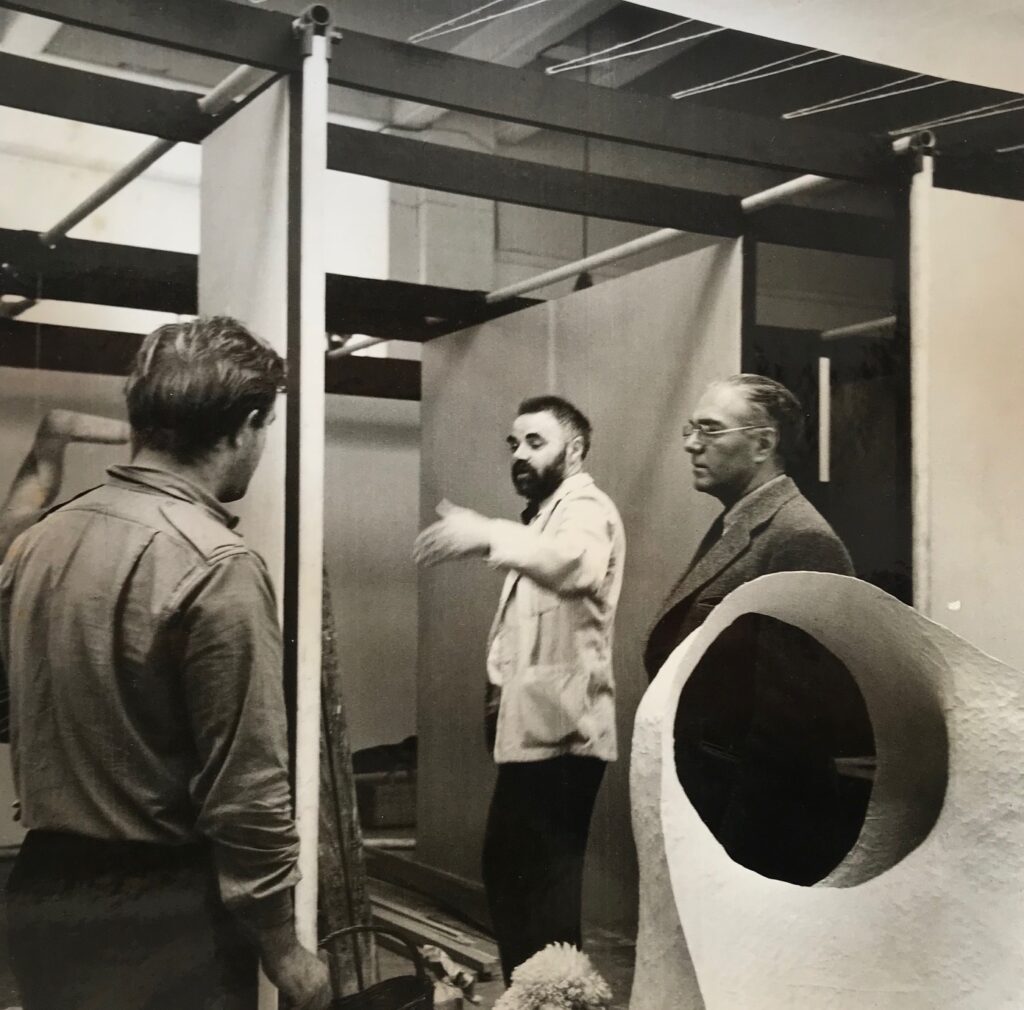

The paintings, including White, Black and Terracotta (1954) are hard-edged abstract compositions, angular, often with interlocking forms. At that time, Barns-Graham was achieving widespread recognition; two years before, the first solo show of her work had been held in London, at the Redfern Gallery. Flowers photographed Barns-Graham and her then husband David Lewis, standing together, but at a slight distance. Having married in 1949, they were a golden couple in the art world, photogenic, stylishly-dressed and very much of the Modernist era, but Flowers’ images also capture a certain awkwardness between them.

Photograph by Adrian Flowers

Born into a well-off family in St. Andrews, Scotland, Barns-Graham studied at the Edinburgh College of Art, where in addition to conventional studio tuition, where the emphasis was on observational drawing, she attended lectures by Herbert Read, and was tutored by William Gilles, whose modernist abstract works were a great influence. In 1940, after spending some time travelling on the Continent, Barns-Graham settled in St. Ives where she met Ben Nicholson, Barbara Hepworth, Borlase Smart, Naum Gabo and Bernard Leach, and began to explore abstraction. Although her early work was representational, and she showed with the Newlyn Society and at the Royal Scottish Academy, Barns-Graham quickly became seen as a leading progressive artist, not only for the quality of her work but also in terms of media coverage of the burgeoning art scene in Cornwall. Her marriage in 1948 to Lewis reinforced this celebrity, especially when he became secretary of the Penwith Society.

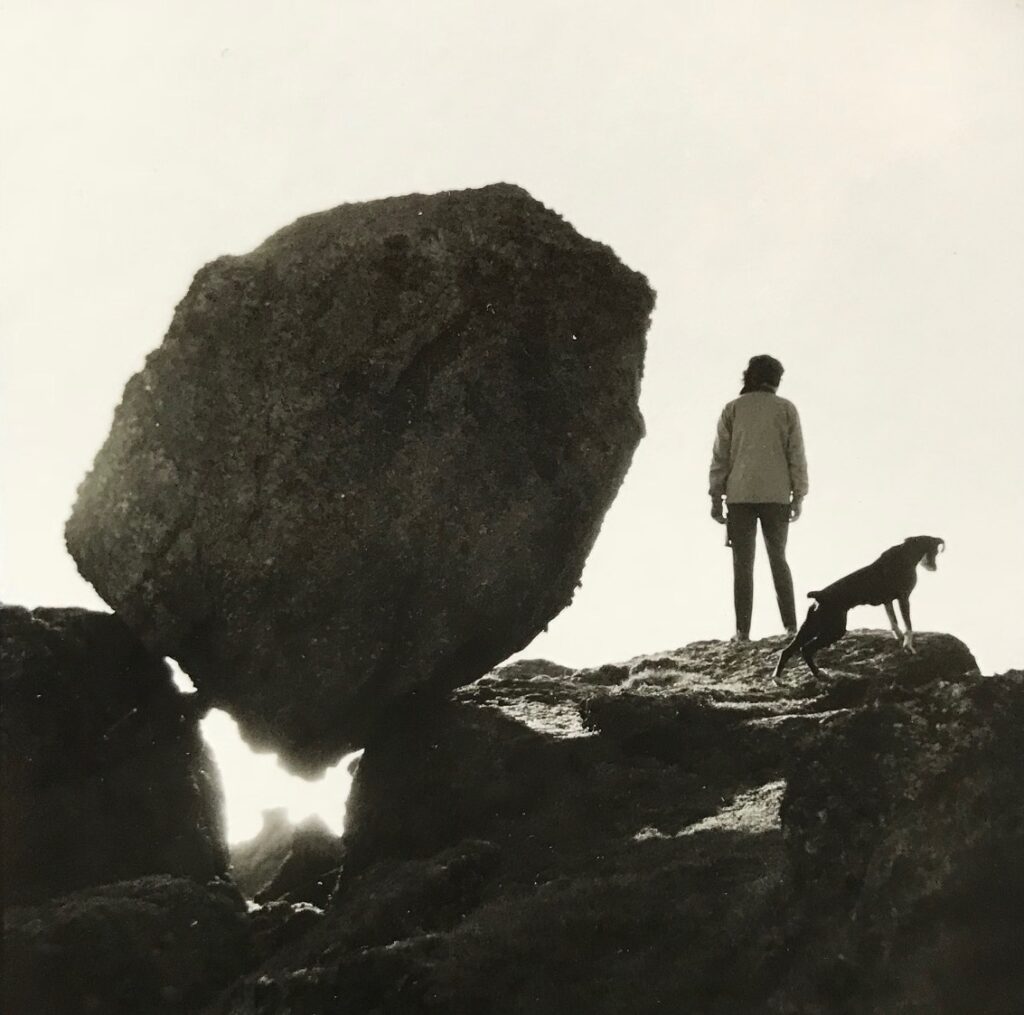

Tall, good-looking, gregarious and charming, Lewis was ten years younger than Barns-Graham. However, having come to Cornwall from South Africa, he was ambitious and by 1954 was beginning to see St. Ives as a cul-de-sac. The year after these photographs were taken, he and Barns-Graham split up, Lewis eventually settling in Canada, where he became a professor of architecture and urban planning. Their marriage was annulled in 1960. Although these events were a blow to Barns-Graham’s personal self-esteem, the set-back was temporary, and while retiring somewhat from the world, she continued to develop her art. Experimenting with different styles, she maintained an abiding interest in geology, which provided, so to speak, a bed-rock for her creative process. This was not surprising, as it was in Edinburgh that James Hutton in the eighteenth century had pioneered the modern interpretations of rock formation. The Cornish coastline and the beach at Porthmeor were a continuing inspiration to Barns-Graham, but from the 1960’s onwards, she travelled extensively, seeking both artistic inspiration and emotional solace in the harshest of landscapes, including the glaciers of Switzerland (which she had first visited in 1949) and the volcanic terrain of the Canary Islands. While her later paintings are more fluid, with colours mixing and merging, the earlier works tend to be hard-edged and geometric. Some echo the fractures and dislocations of faults in strata, while the use of red, reminiscent of liquid magma, is a recurring feature in her art. Barns-Graham’s use of vibrant colours gives her paintings an emotional kick, while her abstract compositions are hard-won, based on close observation of nature, careful thought and inspiration. In the 1990’s she created a series of energetic and colourful paintings, some with a series she titled ‘Scorpio’. Joyous and colourful, these works have echoes of jazz improvisation, and dance. From 1998, at the Graal Press near Edinburgh, she also explored the medium of screen-printing, working with the press’s founders Carol Robertson and Robert Adams. Although Barns-Graham died in 2004, both her work and her contribution to art are sustained by the Trust set up in her name.

[see Virginia Button Wilhelmina Barns-Graham (Sansom & Company, 2020)]

Text: Peter Murray

Editor: Francesca Flowers

All images subject to copyright.

Adrian Flowers Archive ©