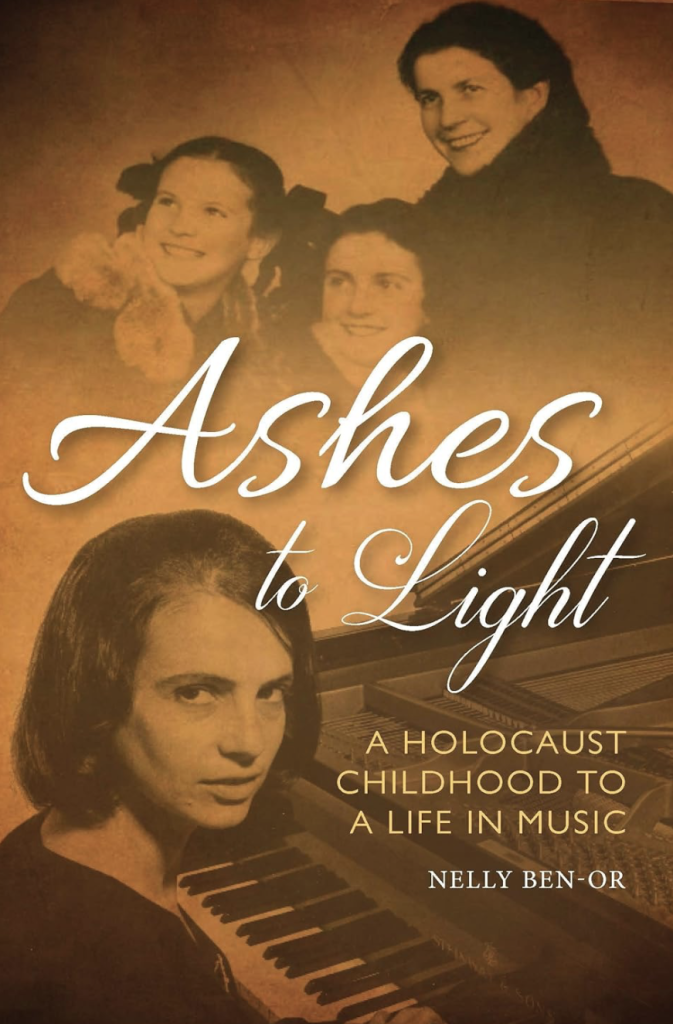

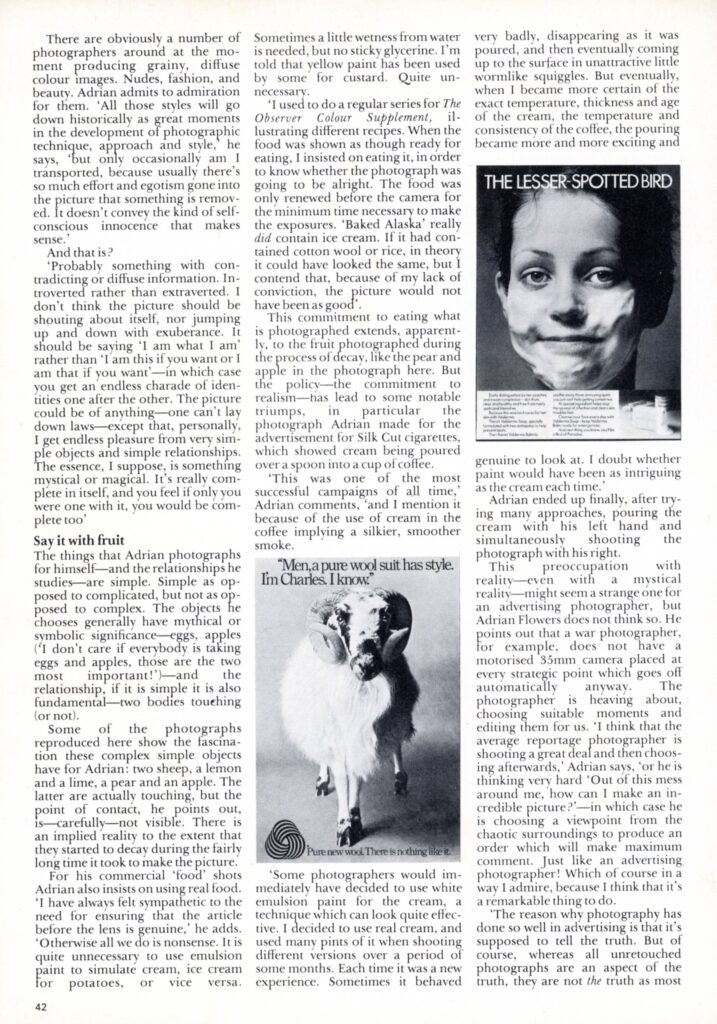

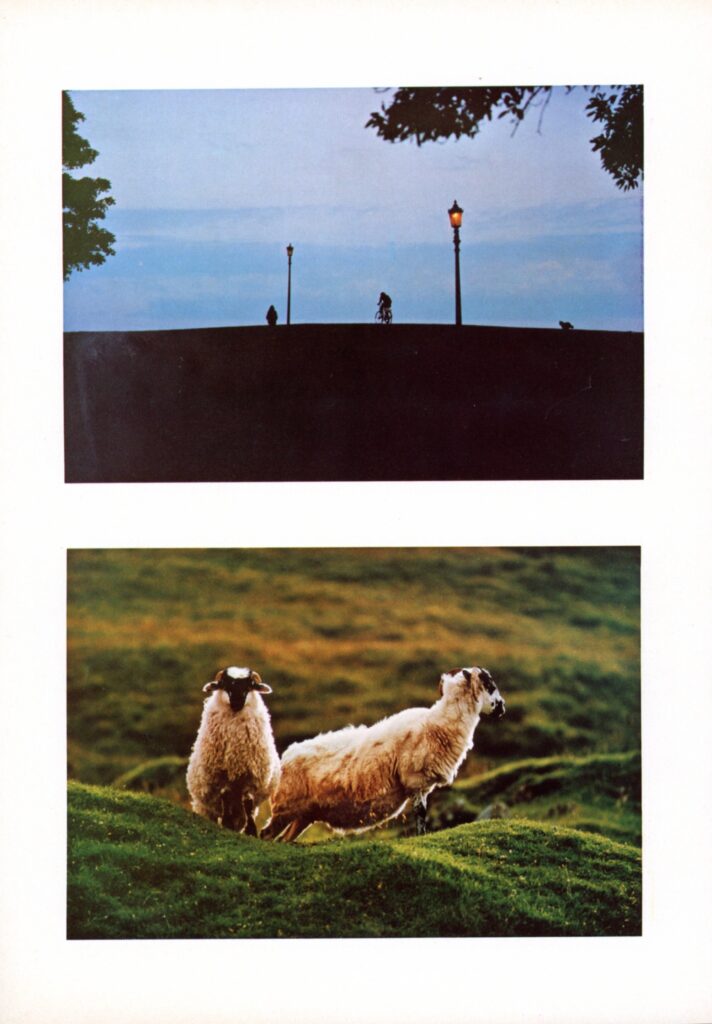

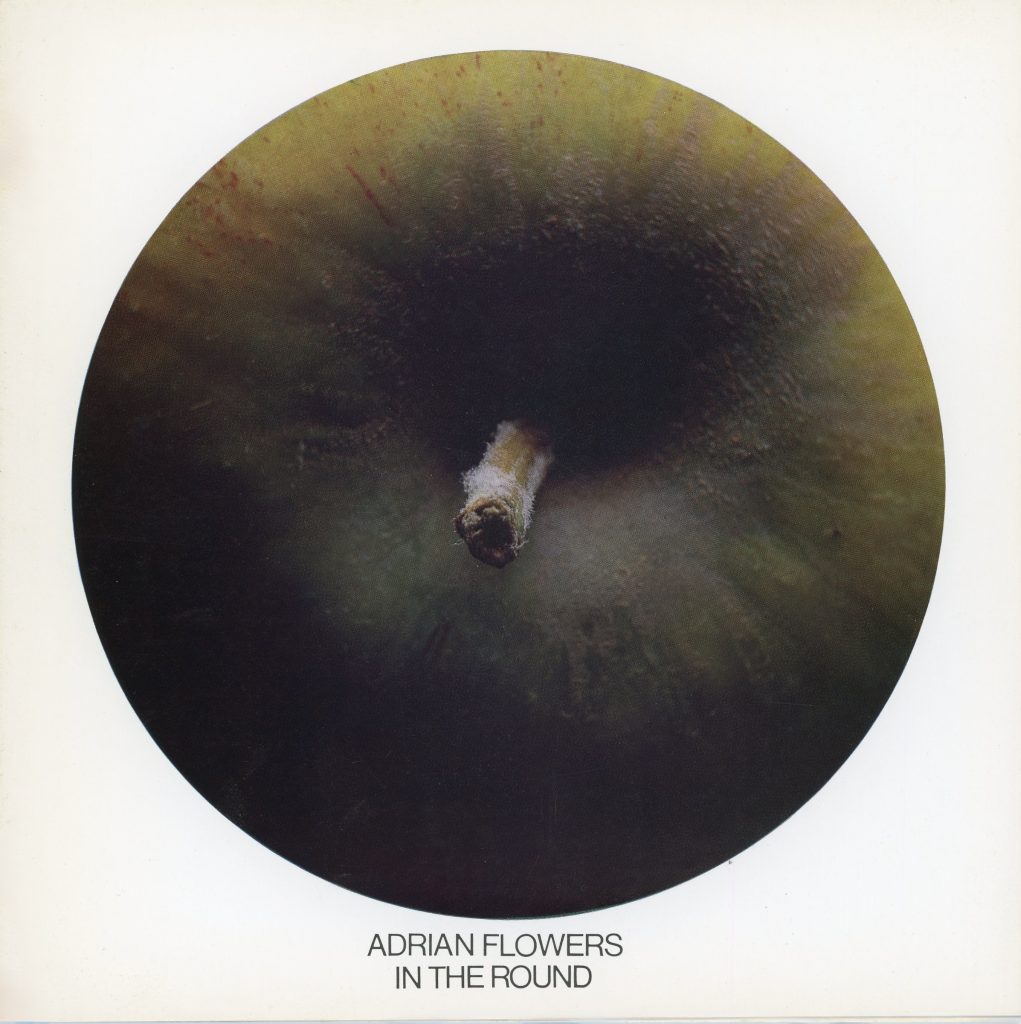

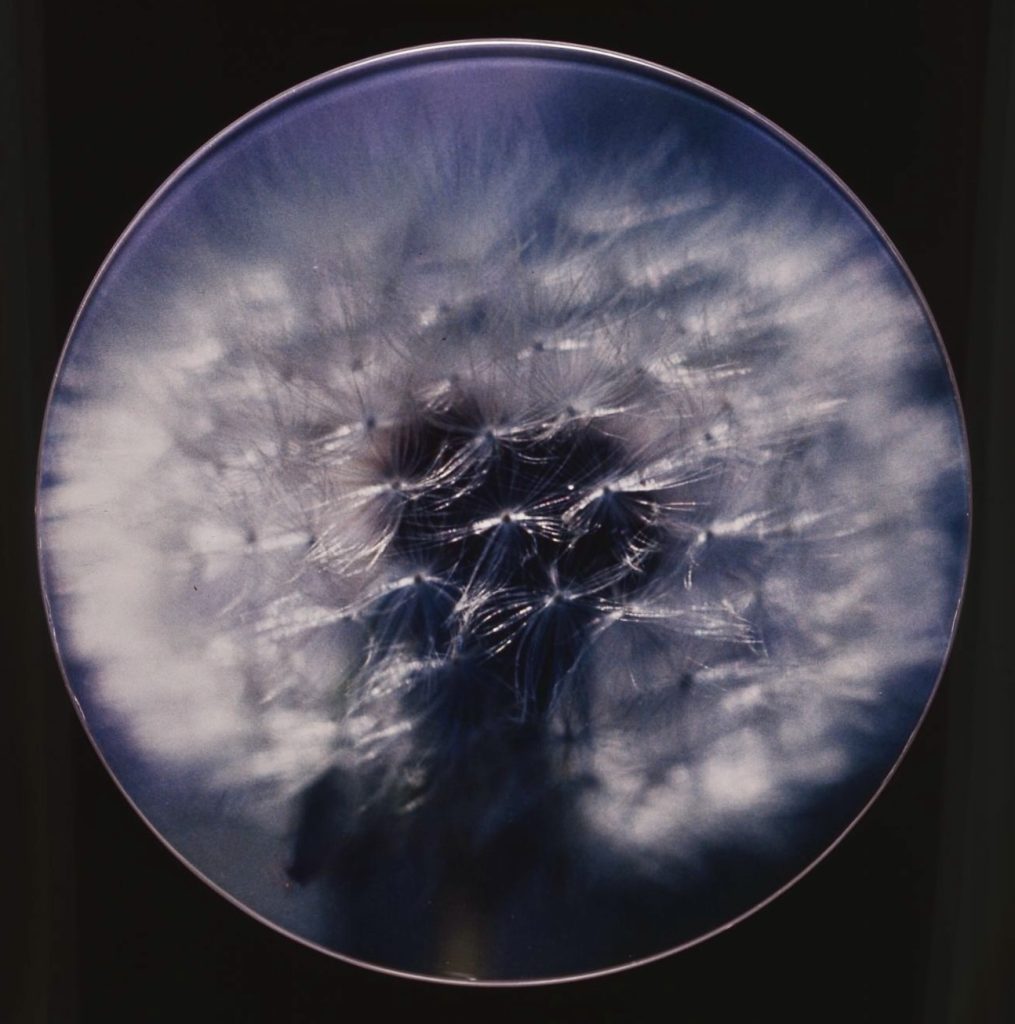

A circular tray of rubber bands, a cricket ball, the spoked wheel of an Aston Martin, a dandelion puffball—these are just a few of the images in the collection of photographs taken by Adrian Flowers and shown in July 1972 at the Angela Flowers Gallery in Portland Mews. The exhibition was titled “One Hundred Pictures In the Round” with each photograph being a circular colour print, 53 centimetres in diameter, encased within a tray frame made of clear Perspex. Although the subject matter was often everyday and down-to-earth, there were no images of plain cups, saucers, plates, or clock faces. Every object had been chosen for its eye-catching qualities, and ability to intrigue and surprise, often with a little shock of recognition. The subjects included a knotted cable, ball of twine and an inflated puffer fish.

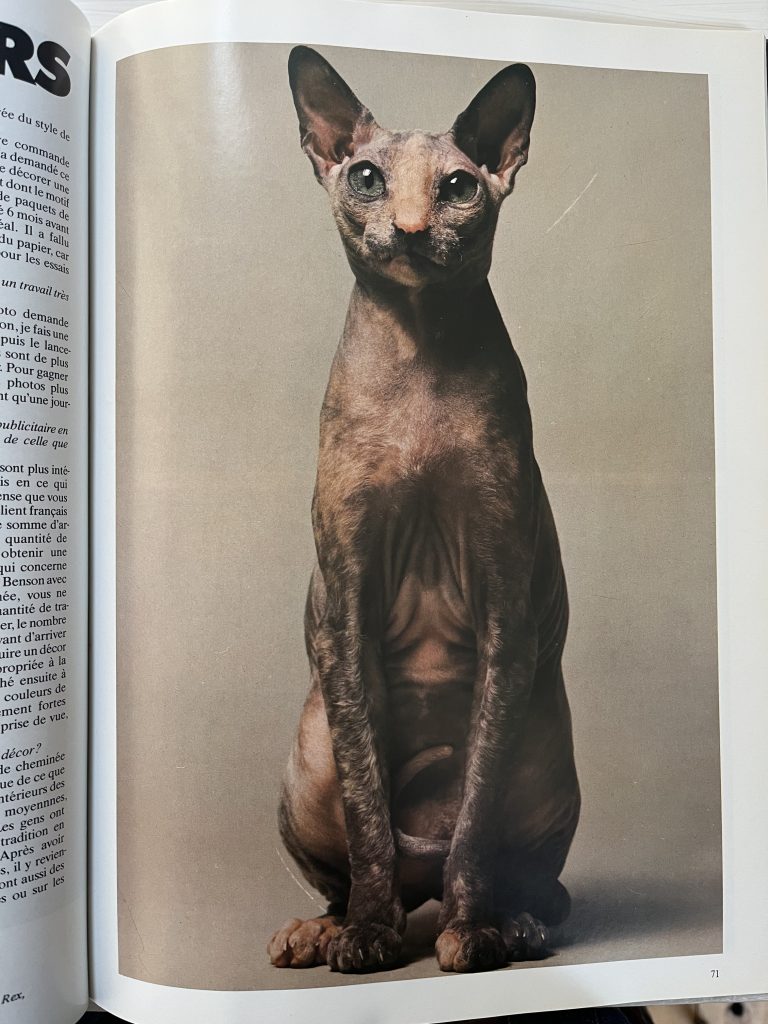

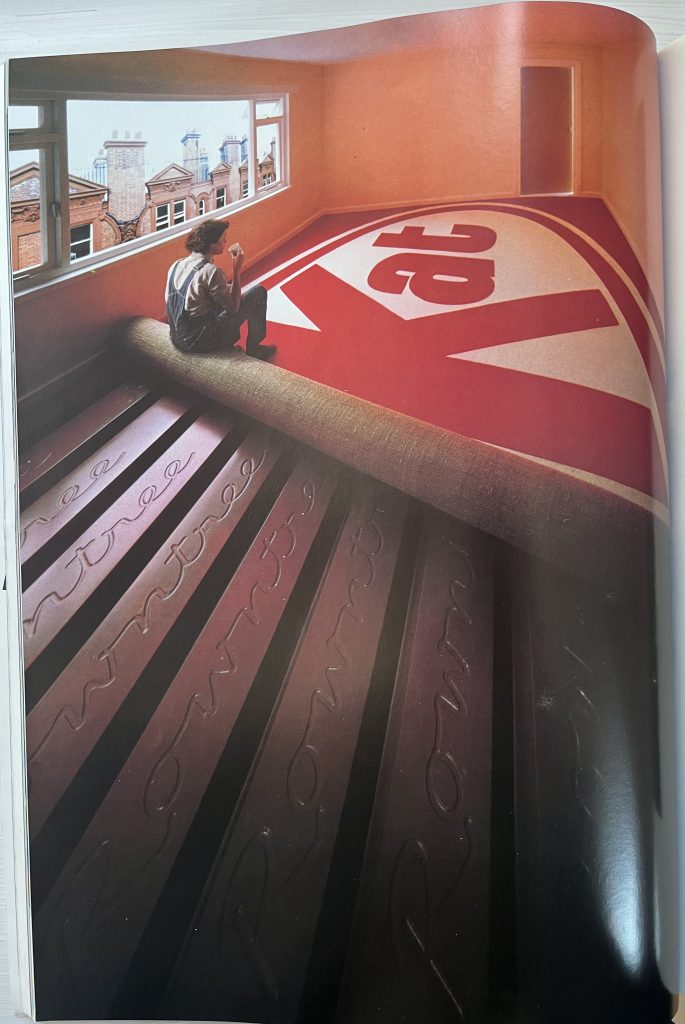

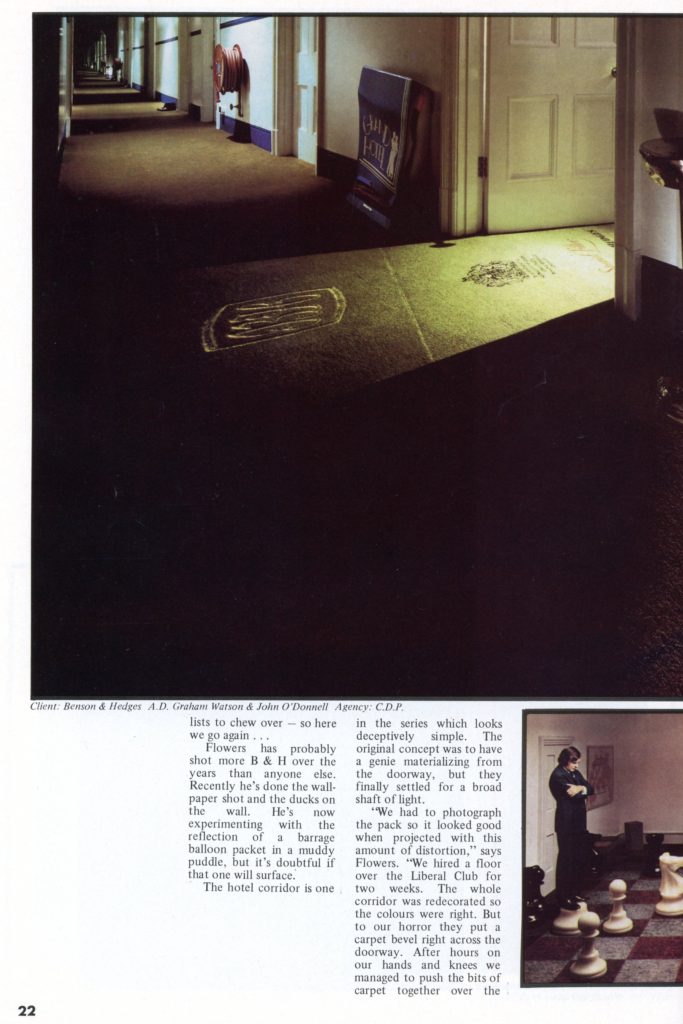

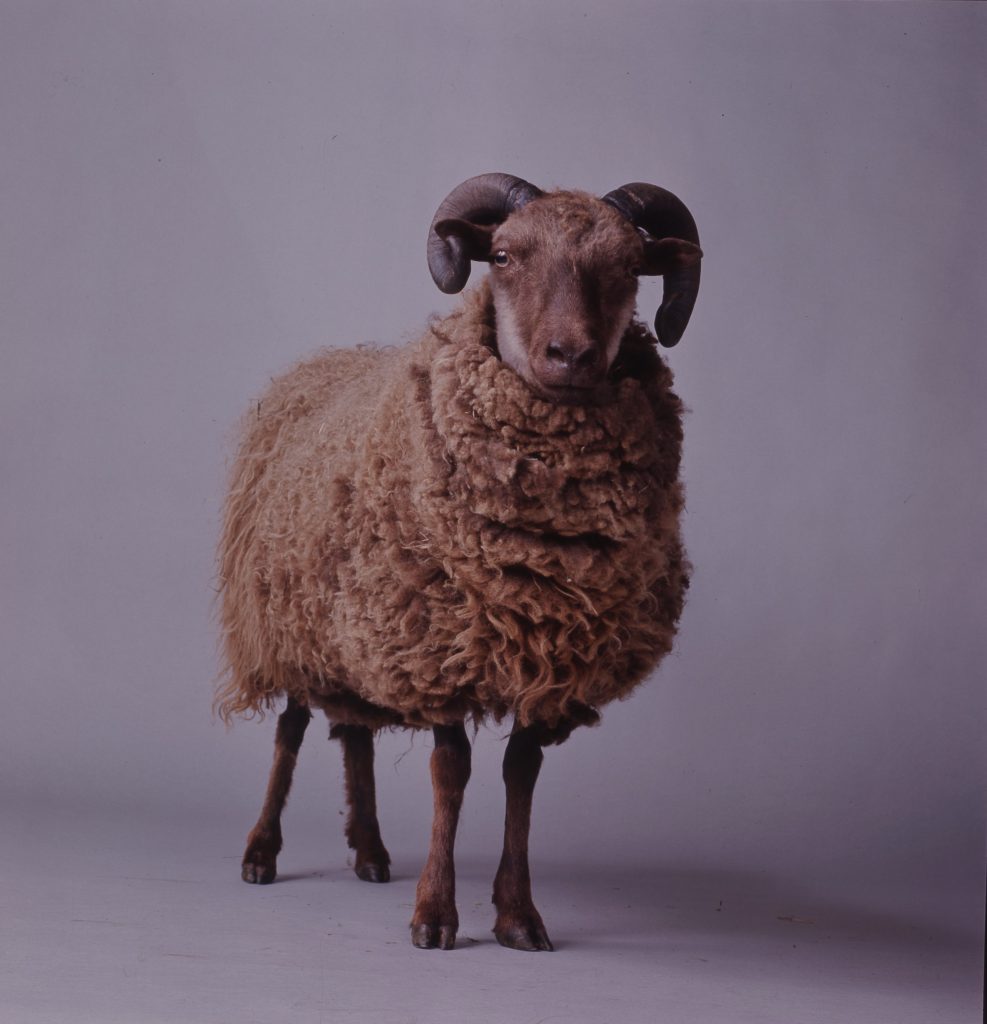

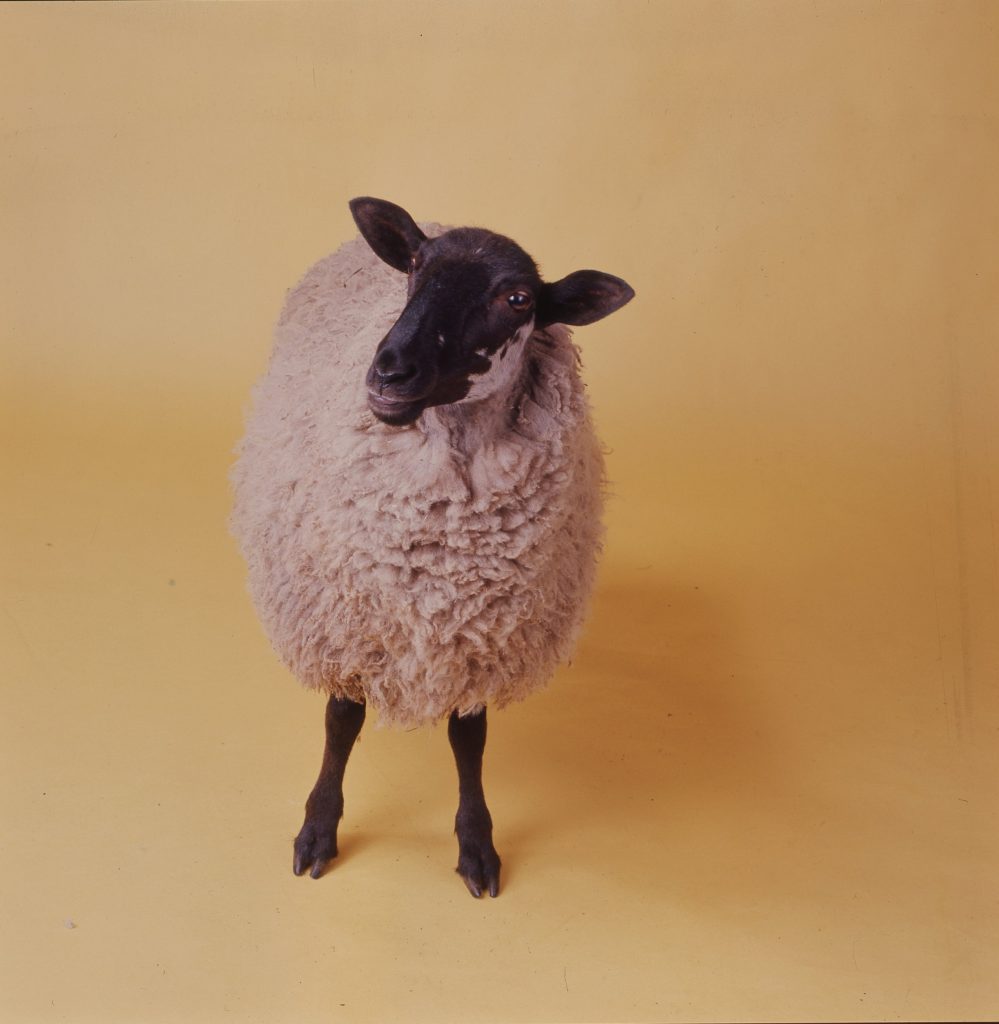

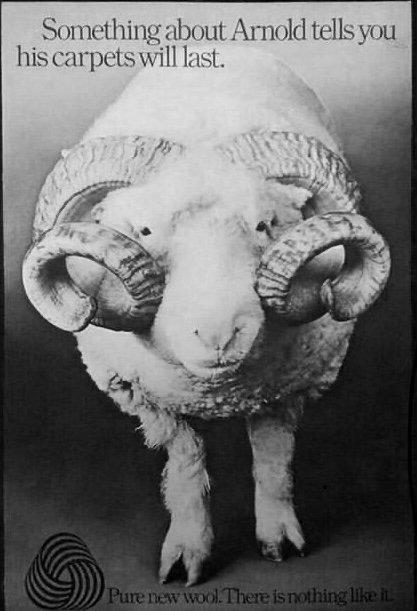

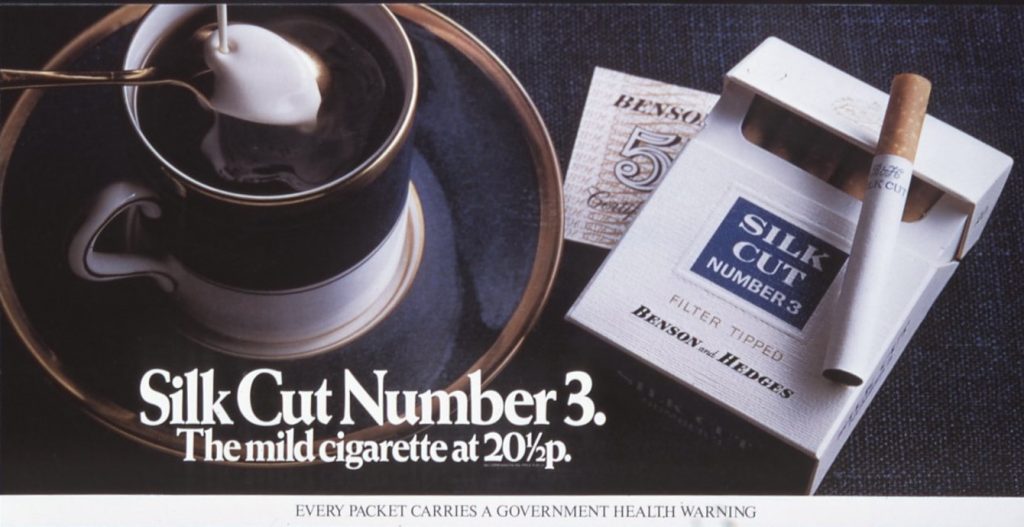

Photograph by Adrian Flowers

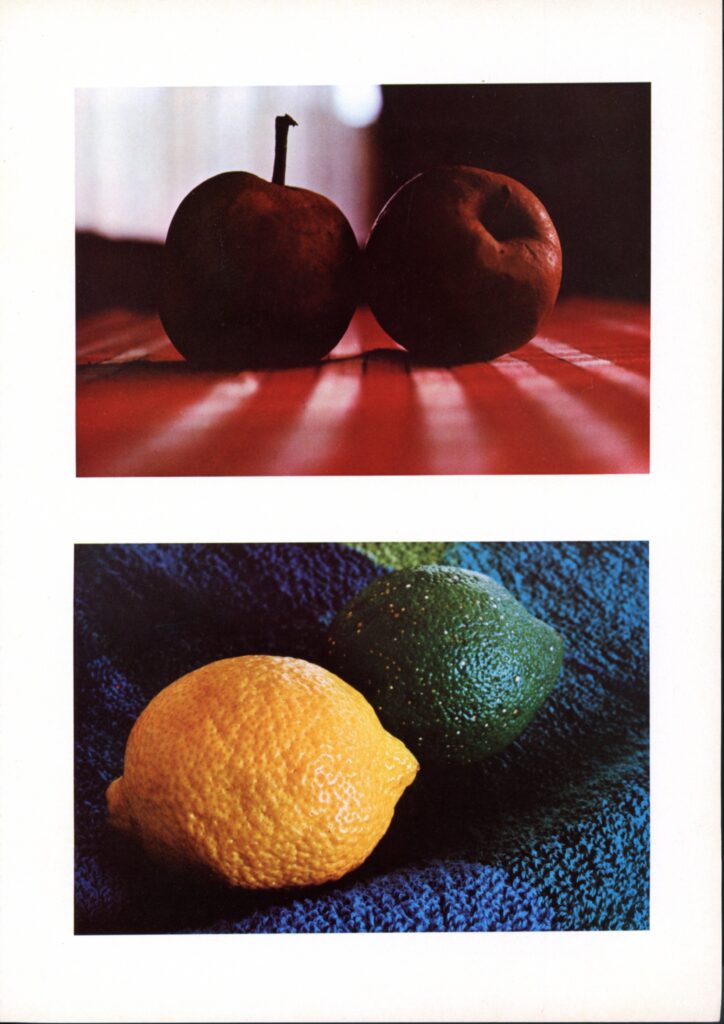

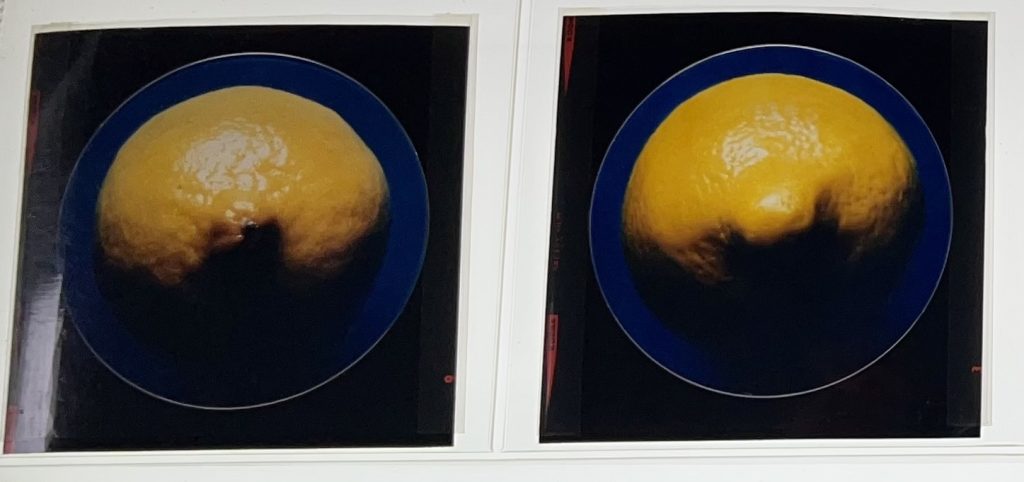

There were photographs of the tip of a pencil, a Yale cylinder lock, an old onion—and the same onion photographed two weeks later. Then there were flowers, with stamens and petals spreading out, a fern unfolding, and fruit, including lemons, apples and pears. A quasi-scientific impulse clearly lay behind Flowers’ choice of subject matter, overlaid with a sense of the surreal. His images evoke the world as seen through a microscope—in this case, the ‘microscope’ being a medium format Hasselblad, and larger format 5×4 camera, with the objects ranging from natural to man-made. Flowers was interested in the real, and the fake: a photograph of a false lemon was set alongside a real lemon. The multiplication of these images, ‘skied’ within the gallery space at Portland Mews, created a hypnotic atmosphere.

His images are fully within the canon of European art. Relishing the idea of momento mori, he would often leave an apple on a shelf, photographing it as the days passed, and the fruit slowly decayed. Two images, Gay Spaghetti and Gay Spaghetti two weeks later, also reveal his interest in mortality, as do the photographs Skull Face, Cat Face and Doll Face. There were no Fabergé eggs, pearls or gold rings in the exhibition, which was dominated by mundane objects; a bath outlet, a full sink, a sink emptying, a tap. Body parts were represented, as in Diffused Belly Button. The only artwork by another artist included was Patrick Hughes’s Vicious Circle.

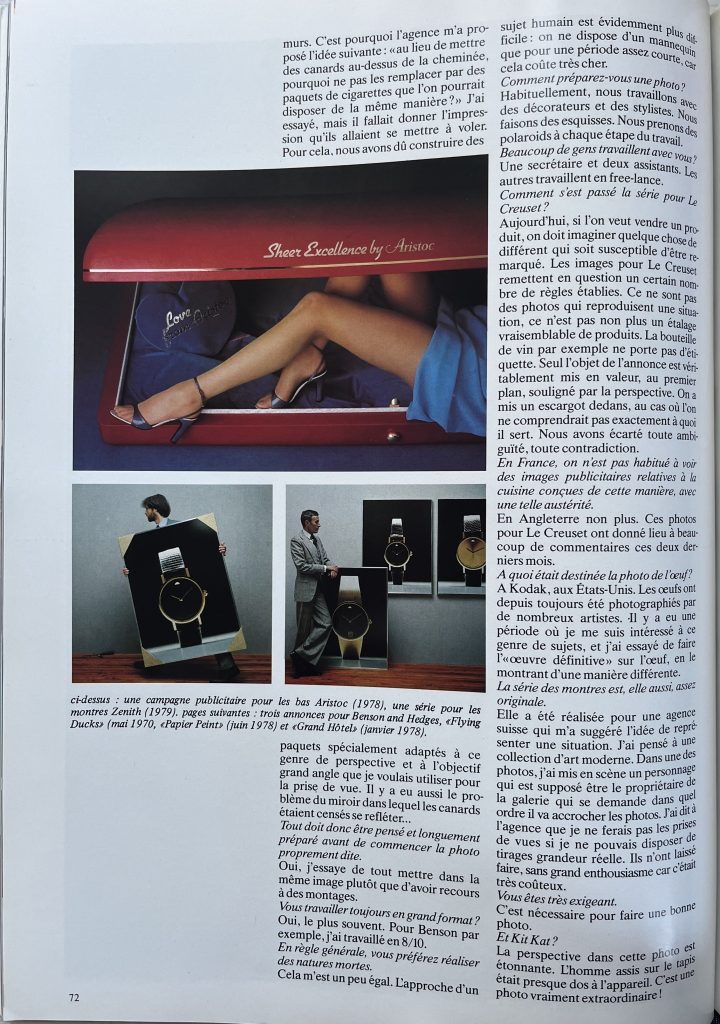

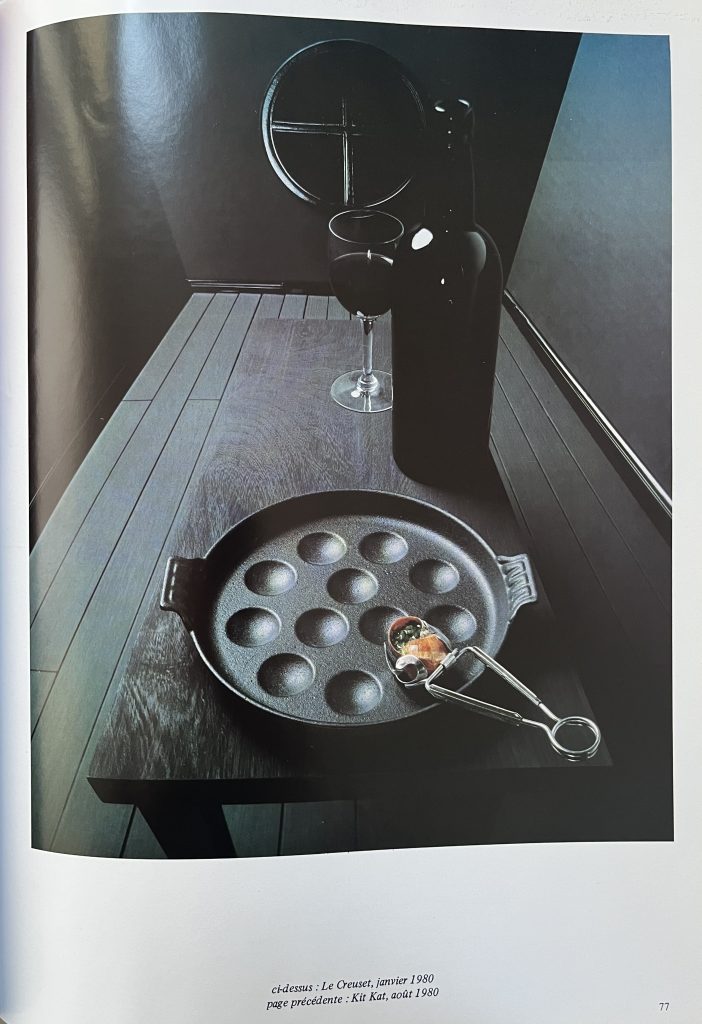

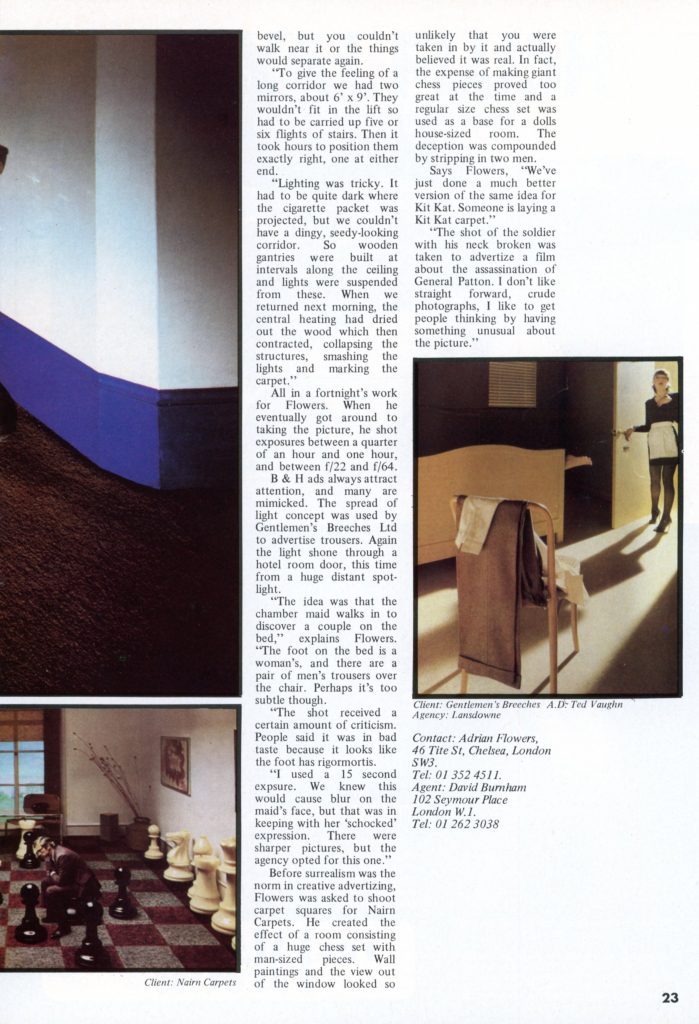

Photograph by Adrian Flowers

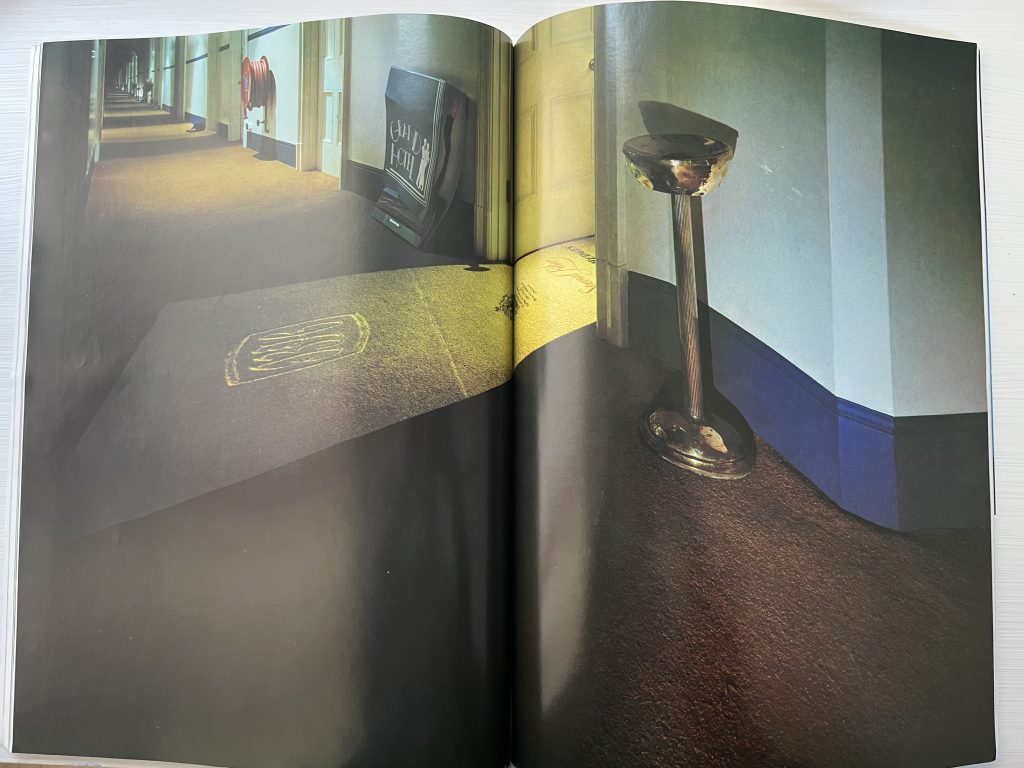

The exhibition was Adrian Flowers’ second showing at the Portland Mews gallery, the first being in November 1970. He clearly invested a considerable amount of time and money in preparing for this second show. He explained his motivation “This exhibition has to do with perspective and subtlety of form, as they can only be understood and sensibly recorded by photography. All these pictures have been confined to the round, which is the shape of the total image as seen through a lens. The content is concerned with the obvious in round objects and with the “in and outness” and secretive nature revealed in so many things.” Critics’ responses to “One Hundred Pictures in the Round” were positive. John Russell in the Sunday Times described it as ‘like a private diary that is at once droll and provocative, lyrical and wryly self-aware’, while Georgina Oliver in Arts Review appreciated how ‘domestic objects acquire an epic, magic quality in a medium completely alive and relevant’. In a more detailed review, Bill Packer of the Financial Times clearly grasped the concept that lay behind the exhibition: ‘The reproductive capacity of the medium is beside the point. It is with photography itself, and primarily with the way in which the camera is able to examine the real world, through its bleak, concentrated and unemotional state, that obsesses him.’ Packer went on to praise Flowers for stepping away from the ‘trivial’ world of advertising and into an art gallery, where his work could be seen on its own terms. While this is an accurate observation, Adrian Flowers actually loved the world of advertising, and felt he was often at his best when working as part of a team, with art directors, set builders and models milling about. “In the Round” was certainly a move to step outside this world, and to position himself as artist-photographer, but more often Flowers would reject the label of ‘artist’. ‘I’m a photographer’ he would say simply.

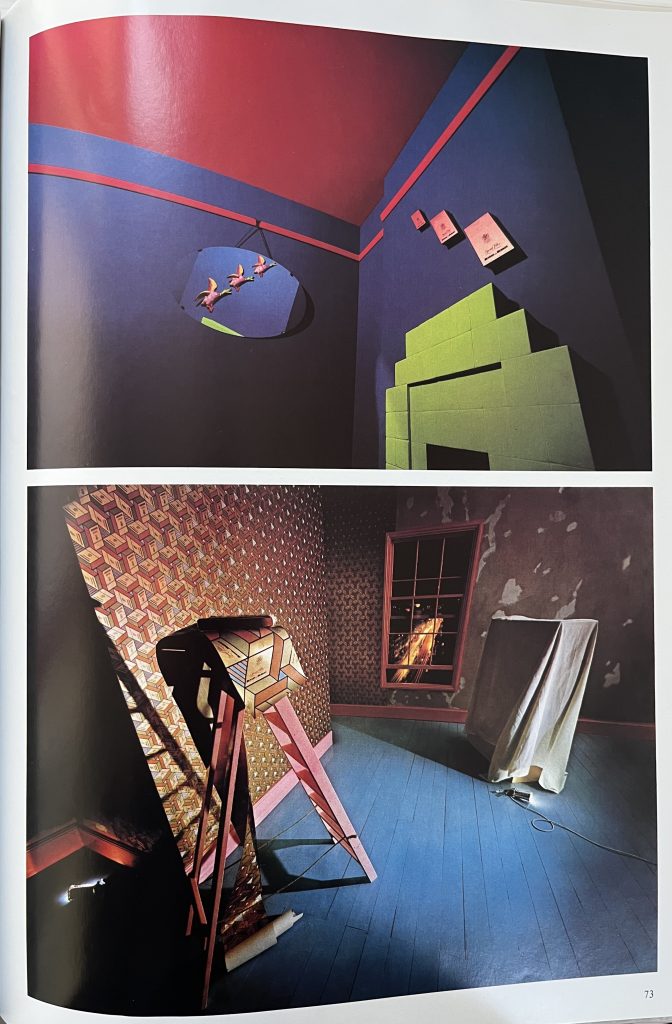

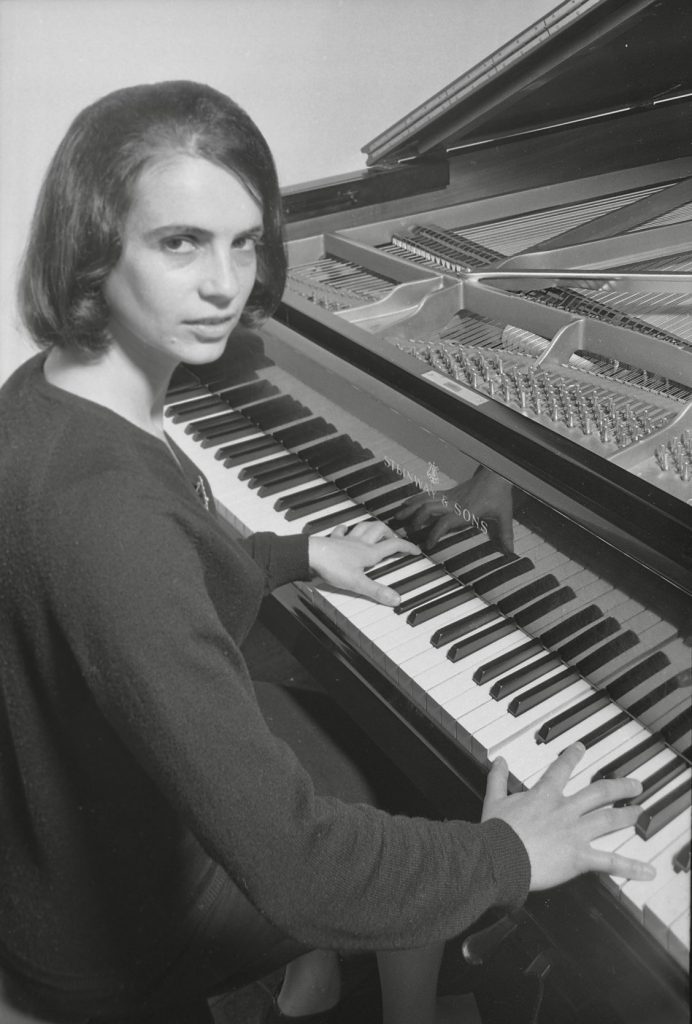

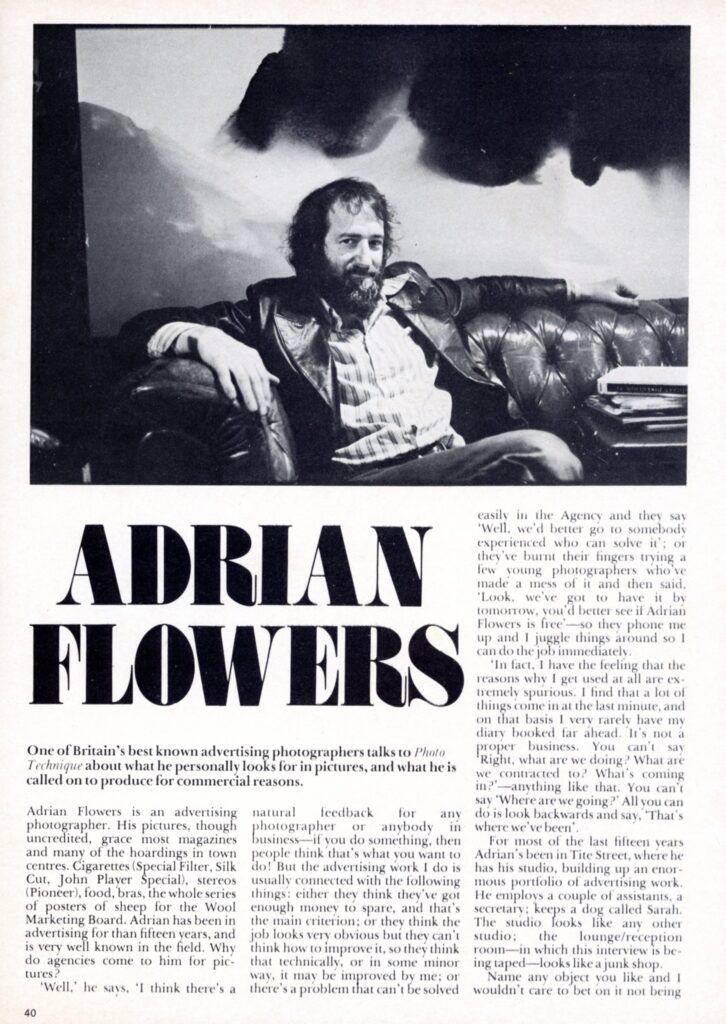

Photograph by Adrian Flowers

But Packer summed up the exhibition with his customary acumen: “And so he examines objects one at a time, baldly presenting them to us, the simplicity of each statement belying his consummate craftsmanship. He takes us through a long and discursive sequence of images, one thing leading to another, often obliquely or ironically. Starting with a perfect green apple, we are shown many aspects of many fruits, which in turn stimulate comparisons with other objects, organic and inorganic. These photographs are very beautiful things, their lack of equivocation, their artlessness, only serving to invest their subjects with an aura of strangeness and ambiguity. And they shrug off the whimsical, and sometimes arch titles and punning cross references as irrelevancies. They do not need such props. Flowers is a considerable artist, and this is a most impressive body of work. The case he makes no longer needs more work like his to demonstrate it to those who will not see it.’

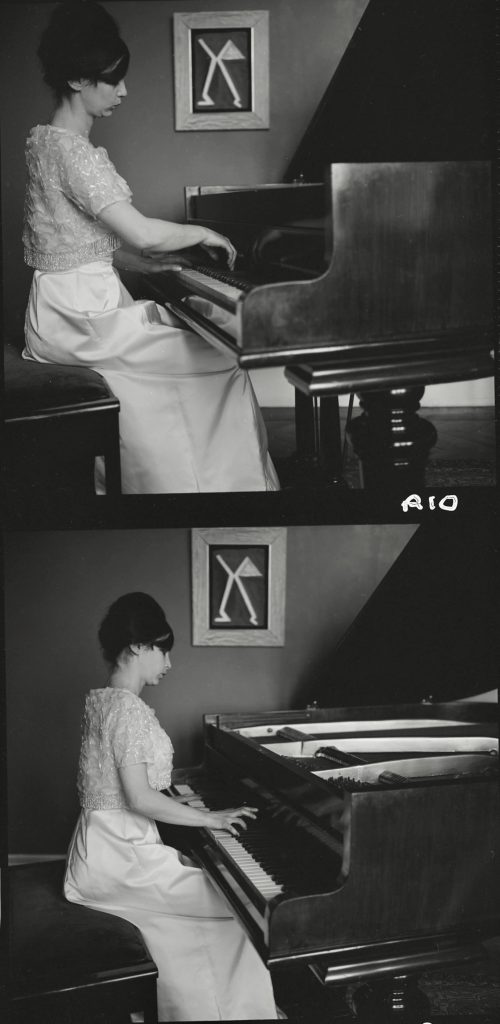

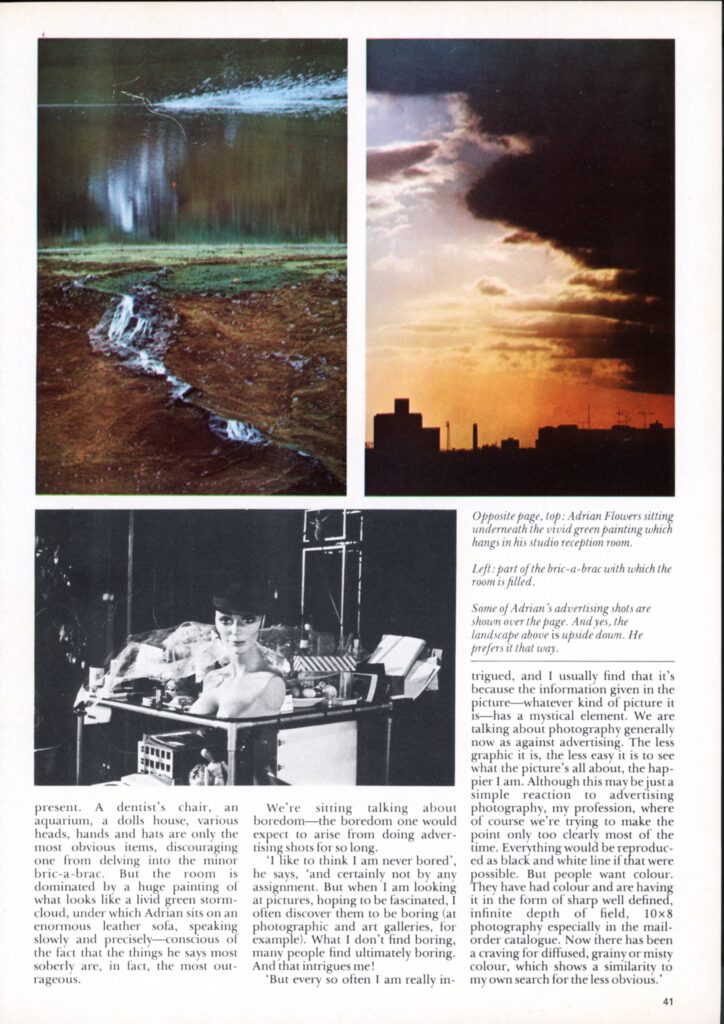

Photograph by Adrian Flowers

Leo Stable, pioneering curator at the Photographic Gallery in Southampton, also responded to the artistic quality of the show, writing to Angela Flowers in 1973 to ask if “In the Round” could be shown in his gallery. Originally from Lancashire, Stable studied in Sheffield and would go on to become a founding director of the John Hansard Gallery at Southampton, which today is one of the leading galleries in Britain specialising in photography. It was likely through Stable’s introduction that In the Round was shown at the Graves Gallery in Sheffield.

Packed in ten crates, the works were then shipped to New York, to be shown at the New York Cultural Center at Columbus Circle, in association with the Fairleigh Dickinson University. From there the exhibition went to the Hopkins Centre Art Gallery at Dartmouth College. Several works were sold during its showing at Portland Mews, with Roland Penrose, Len Deighton and Patrick Hughes being among purchasers. Penrose and Deighton acquiring Rose and Cat Face respectively. Today Rose is among the artworks on show at Farley Farm in Sussex, the home of Roland Penrose and Lee Miller.

Text: Peter Murray

Editor: Francesca Flowers

All images subject to copyright.

Adrian Flowers Archive ©

For further information, please contact Francesca – adrianflowersarchive@gmail.com