In late November 2022, we visited the photographer Neil Selkirk in his house and studio, a stone’s throw from the David Zwirner Gallery on W.19th Street. Opening a little iron gate with a latch, we descended three steps from street level, to an oak door. Selkirk greeted us and led us through a little courtyard to his home at the rear of the building.

Inside, a lit wood-burning stove added a warm glow to the arts and crafts interior, with its dark roof beams and wooden kitchen presses. On a large wooden table, a scattering of autumn leaves and branches made a colourful display. Mounted on the wall, an ornate silver tray bore an engraved testimonial to a Selkirk forebear from the congregation of a Free Presbyterian Church in Glasgow. Even after decades of living and working in the United States, Selkirk, a cheerful conversationalist, retained his English accent. As he prepared coffee, he described his years in New York, his pride in his two children, now grown adults and working in the city, evident. Although divorced from his wife Susan, he radiated confidence and a contentment with life. “I’ve been lucky”, he commented, although this underestimates his achievements gained through skill, hard work and dedication to photography. He made coffee with the same attention to detail as though he were in a photo lab, grinding the coffee beans, and carefully preparing the steamer for warming milk.

Selkirk’s own photographs have featured in Esquire, The New Yorker, The New York Times Magazine, Interview and Vanity Fair. For over a decade he also worked in the corporate world, taking photographs for annual reports. His exhibition of portraits Certain Women was held at the Howard Greenberg Gallery in 2015. At the time of our visit, he was working on a series of close-up still life photos of bar-room toilet door locks entitled Security Matters. Printed in a large scale, several of these decorated the walls of his studio in the basement of the building. It was formerly a fully-fledged darkroom, complete with water filters and sinks, but no longer used for darkroom printing.

Best-known in the art world for his work printing the photographs of Diane Arbus since her death, Selkirk was born in London in 1947. After initial studies at Chiswick Polytechnic, he graduated from the London College of Printing, and aged twenty-one, embarked on a life-long career as a photographer. From the outset, he demonstrated a deep understanding of the science of the process; developing and fixing film, and utilising advanced printing techniques. Keen to work with the best photographers, even as a student he travelled to France and the United States. In March 1968 he was in New York, visiting the studios of leading photographers and offering his services as an assistant. This direct approach worked, and he was offered work, not only by Richard Avedon, but also by Irving Penn, Melvin Sokolsky and Bert Stern. Fortuitously, Selkirk even found himself on 40th Street, photographing Bobby Kennedy outside the New York Press Club just after he announced his candidacy for president. Although he accepted a job offer from Penn, it transpired the studio was unable to obtain a work visa for him. In the meantime, Avedon had been asked by an English advertising agency to work on a cigarette campaign and came to London, where Selkirk worked for him as an assistant.

When Selkirk realised that getting a visa to work in the US was not going to be straightforward, he sought employment in London, and was taken on by Adrian Flowers, [on 9 September 1968] at his studio in Tite Street. In a recent interview with Elizabeth Avedon (former daughter-in-law of Richard) Selkirk recalled his time there; affirming how Flowers was ‘a big name’ in the London photography scene from the 1950’s through to the early 90’s. Flowers’ studio was ‘the place to be photographed’ for advertising and editorials, and for actors, celebrities and artists.

While working at Tite Street in 1968 and the following year, Selkirk assisted Flowers with a number of advertising jobs, including trips to France and Italy, and photographing products, even Christmas puddings. He explained how photographs taken in London were sent to New York, to be converted into dye-transfer prints, an expensive and technologically advanced method that gave high-quality reproductions for magazine advertisements. At that time there was no dye-transfer lab in London. On one occasion, when a large 15 x 12 inch duplicate transparency, made from a standard 35mm negative, was sent back to the studio, Neil was so impressed, he immediately went in search of a large-format camera capable of making large negatives. At Brunnings, the photography shop in Holborn, he found two such cameras, dating from at least the 1920’s. He bought both cameras, and still has them.

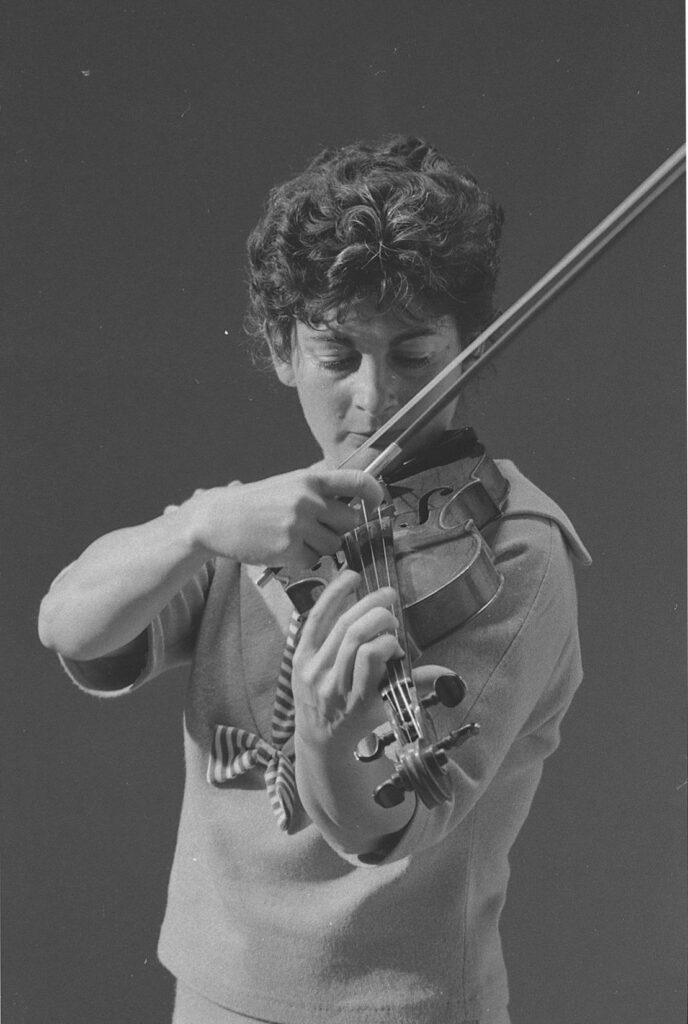

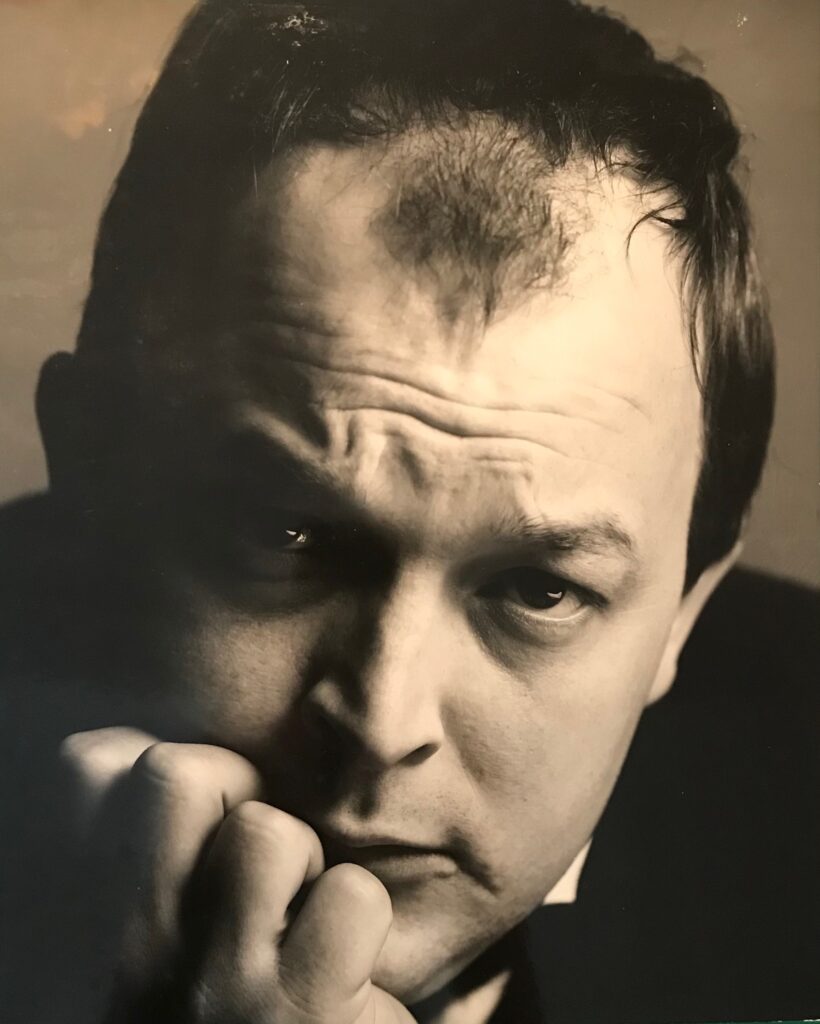

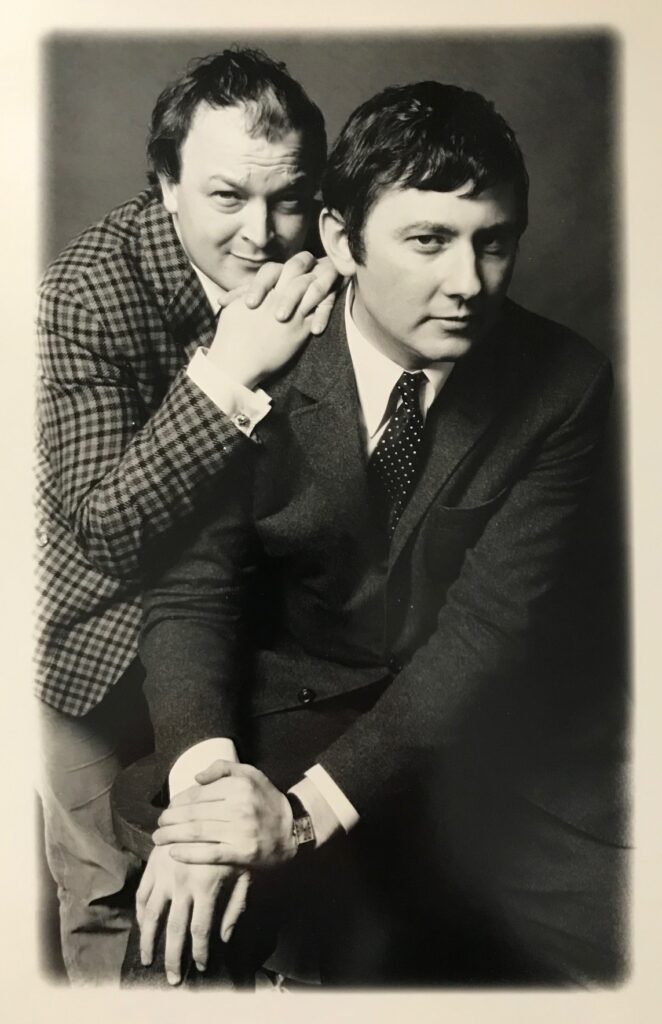

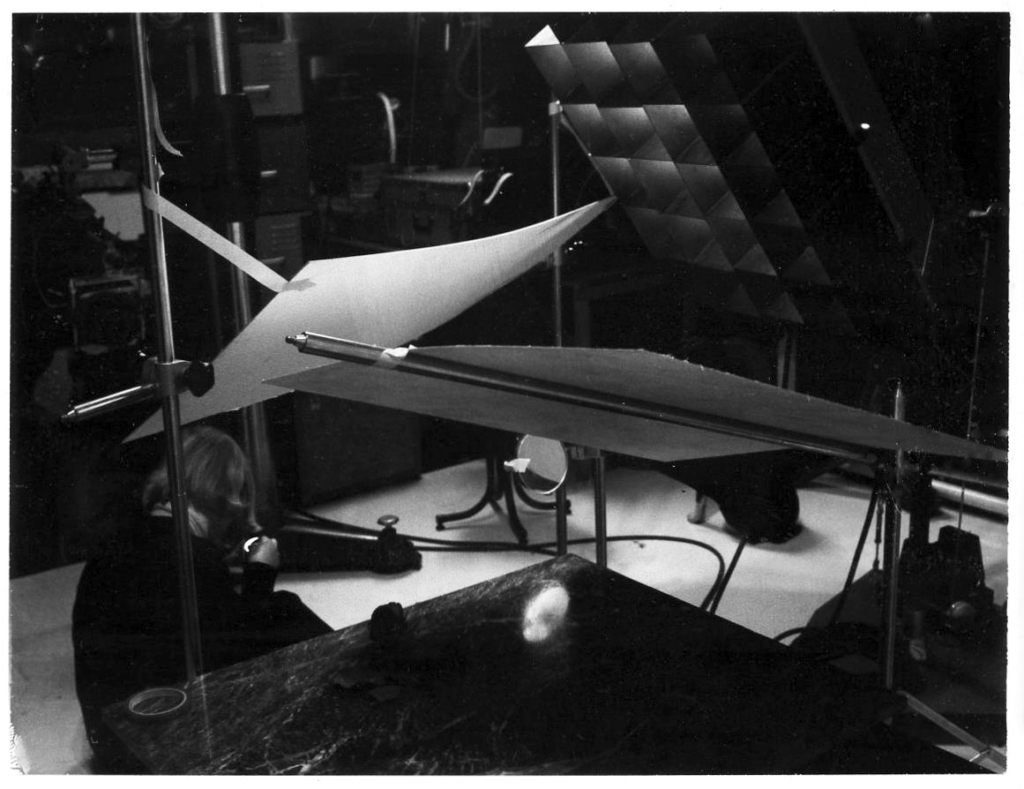

Photograph by Adrian Flowers

Selkirk recalled his time working with Flowers in London with delight and occasional chagrin. One time, the leg of a heavy tripod had unexpectedly slid down and injured his foot. In spite of the pain, and the wound taking a long time to heal, he continued to work, standing behind Adrian, ready to hand over film and equipment as needed. However, Adrian had a habit of stepping backwards when he was working and did so several times, stepping on Selkirk’s injured toe. He looked back in surprise to see his assistant bent over in agony. Selkirk laughed as he recalled this. But even at the Flowers studio, he was ambitious to move on and establish his own career. Through Avedon, he was offered a short-term contract in Paris, to assist Japanese photographer Hiro (Yasuhiro Wakabayashi). A decade earlier, Hiro had himself been an assistant to Avedon. Selkirk requested leave of absence from Tite Street, to work on this project with Hiro. Flowers responded “And what if I say no?”. “In that case”, Selkirk cheerfully replied “I’ll quit”. But Flowers relented and let him go. Back in London, Selkirk, who now admits that he must have been insufferable at the time, describes Flowers addressing him in quiet desperation “I know you’ve worked with the most famous photographers in the world, but would you mind passing the film holder”. In stories such as this, Selkirk revealed a self-awareness and self-deprecating sense of humour. “I’m sure I was impossible”, he acknowledges.

The shoots he worked on included trips to Malmaison, outside Paris, and to the Medici palazzos in Florence; both for the Observer magazine. Also for the Observer Selkirk accompanied Flowers to Bonn and Vienna to assist on the Beethoven feature [see previous blog post on this site].

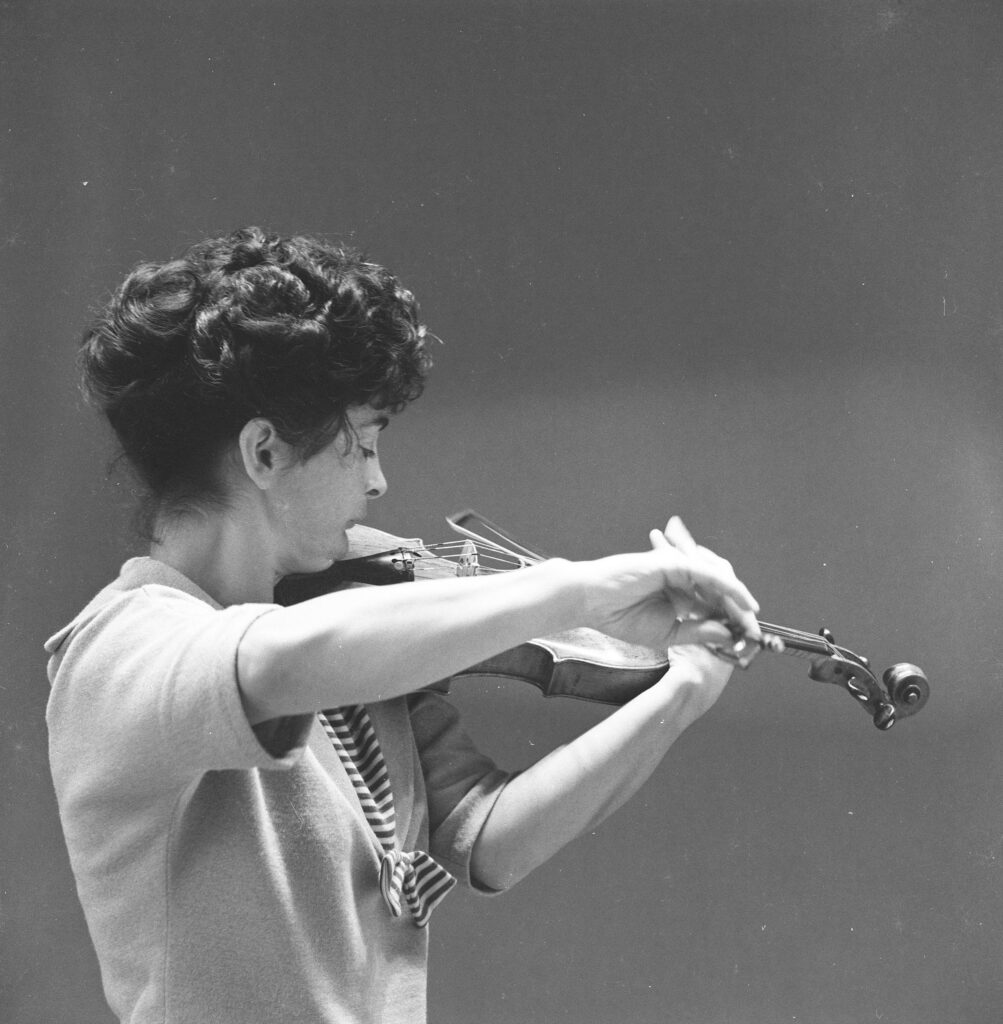

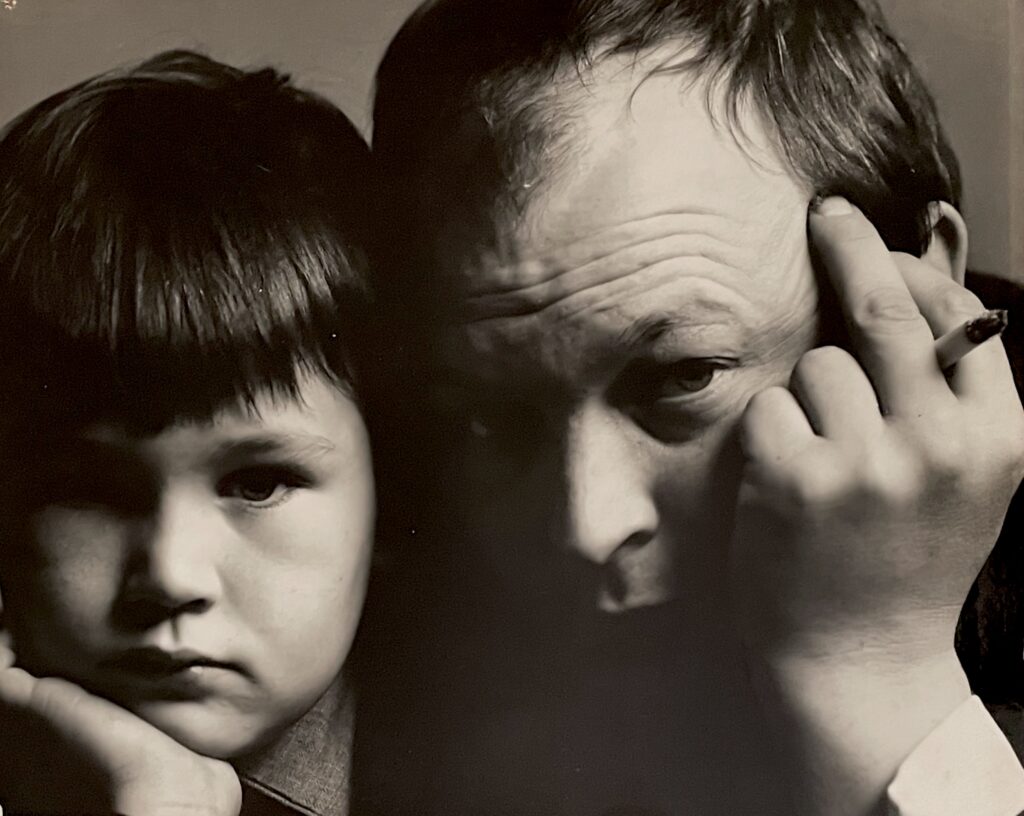

photographed by Adrian Flowers in Bonn, Nov. 1969 for the Observer magazine

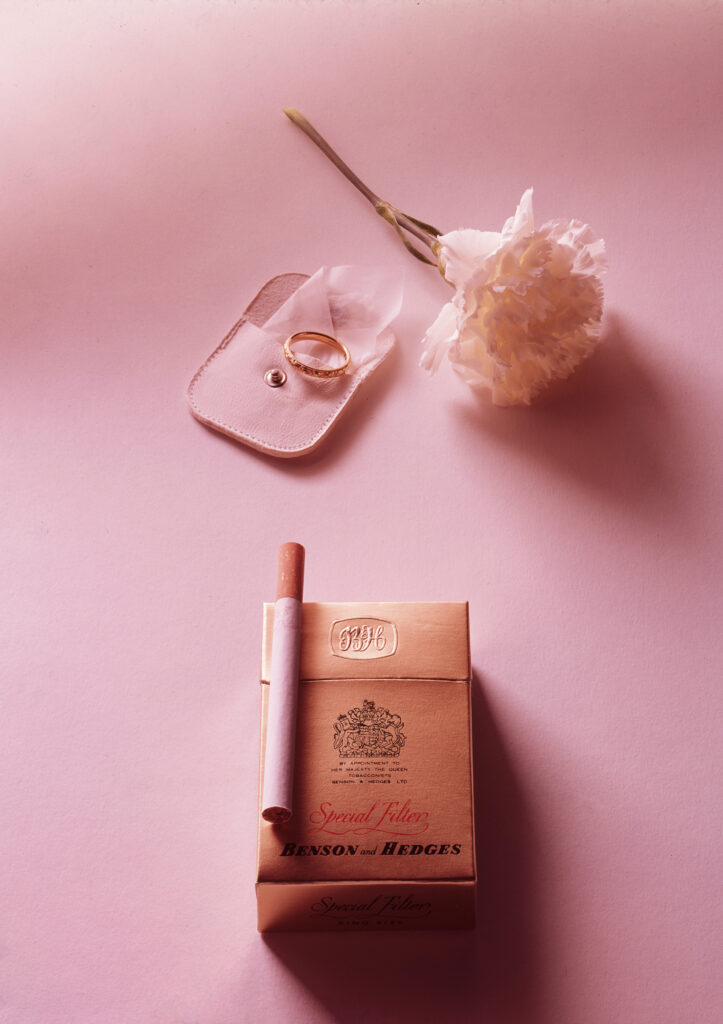

Selkirk also worked on several of the early Benson & Hedges ads, the ‘Gold Box’ years.

Collett Dickenson Pearce (CDP)

Photography: Adrian Flowers

Another memorable job was for the book cover of Len Deighton’s An Expensive Place to Die, art directed by Ray Hawkey [see previous blog posts on Deighton and Hawkey]

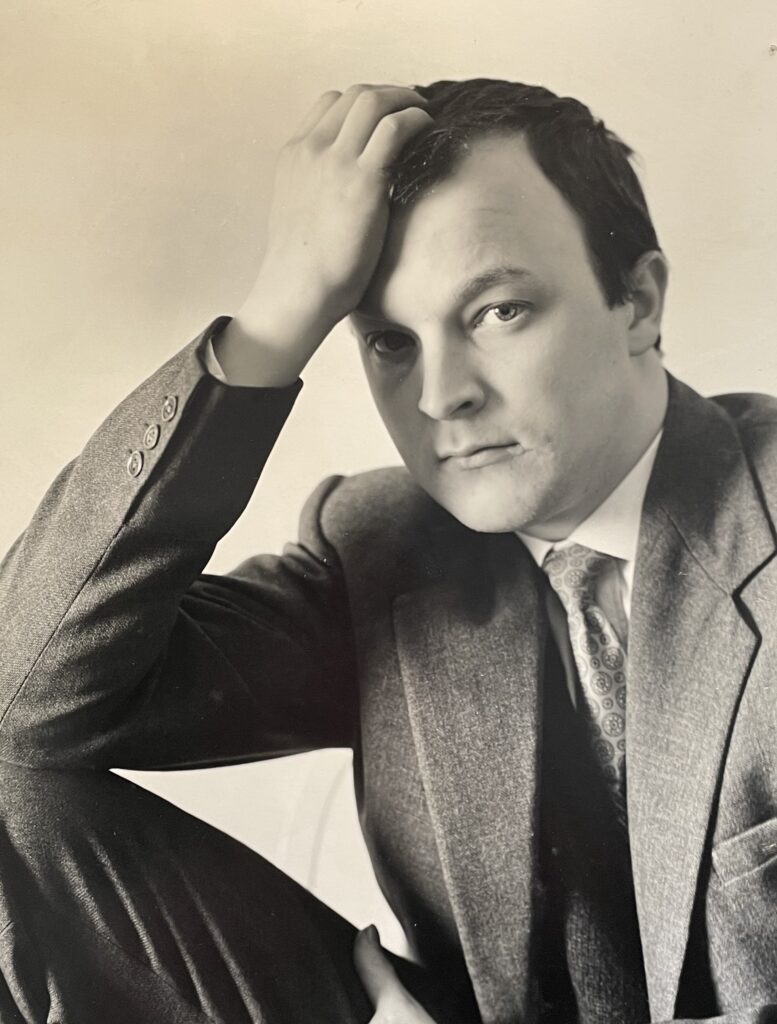

Photograph by Adrian Flowers

However, in London, Selkirk was earning just two pounds and ten shillings a week as an assistant at the Flowers studio and knew he had to move on. Working at Hiro’s studio in 1970 and ‘71 had led to further opportunities; while there, he met Diane Arbus and her friend and collaborator Marvin Israel. Arbus invited Selkirk to participate in a master class she was giving. He was more than just a student; at that time Arbus was looking to move on from working in the 2¼ square format, and was researching larger format cameras. Hiro had been using one of the first Pentax 6 x 7 cameras, which took the 120 film Arbus was experienced with, but produced larger images. Familiar with this camera, Selkirk showed her how to use it. After working at Hiro’s until July of that year, he then went to work for fashion photographer Chris Von Wangenheim. This brought him back to Europe, to Rome and Paris. While in Paris, he learned of the death of Arbus, and wrote a letter of commiseration to Marvin Israel. He also offered his services, should a book or exhibition be organised in the future.

Back in New York, Selkirk immediately was put to work by Marvin Israel, working on the forthcoming Arbus exhibition to be shown at MoMA, and on the monograph “Diane Arbus”. He jumped at the opportunity, however he was faced with an intimidating task: Arbus had never labelled or dated her prints. Selkirk was baffled as to how she found a negative. She evidently had a system, but only she knew where things were. Selkirk’s work making prints for the 1972 book and show were intended to be a one-time project, but evolved over the years into his being the only person ever authorized by the estate to make prints from Arbus’s negatives.

For many years now, Selkirk has worked with Doon, eldest daughter of Diane Arbus, who manages her mother’s estate. They periodically are involved in organising exhibitions such as the recent one, entitled “Cataclysm” at the David Zwirner Gallery, that reprised the 1972 MoMA show. The accompanying publication, Diane Arbus Documents a massive tome of several hundred pages, contains Fifty years or more of reviews and essays by Susan Sontag and others, along with an extensive bibliography. It is co-published by Zwirner and the Fraenkel Gallery, with David’s son Lucas guiding it through many stages of development. Doon is also a writer, and in addition to producing books of her mother’s work, has collaborated with Richard Avedon on many projects, including The Sixties, and has recently published her first novel, The Caretaker.

There was a pause in the conversation as Selkirk put a log in the wood-burning stove that added a bright touch and warmed the apartment. Beside the stove was a stack of split wood logs. “The difficulty”, said Neil, “is getting the logs all the way from my place in upstate New York to this room, they’re so heavy!”

In his last years at the old mill – the moulin, in France, Adrian Flowers would often photograph logs from the wood stack. He would set them up in rows outside the barn. Lit by the evening sun, each log acquired its own personality. The photographs were like distant memories of the actors, artists and celebrities who had visited the studio at Tite Street half a century before.

Neil Selkirk website: neilselkirk.com

Text: Peter Murray

Editor: Francesca Flowers

All images subject to copyright.

Adrian Flowers Archive ©