1908 – 1998

On 7th January 1956, on the first floor of a house in Blackheath in south London, Adrian Flowers set up his studio lights and large-format Sinar camera, to photograph works by the artist Victor Pasmore. Facing the heath, the three-storey Georgian house was large enough to accommodate both the artist’s studio and family living space. Victor and Wendy Pasmore (née Blood) had moved into this bomb-damaged but elegant house in 1947; their son John was born there in 1953. On this day, and during at least one subsequent visit, using 35mm and 120 film, as well as large-scale colour transparencies, Flowers photographed Pasmore, his studio and artworks.

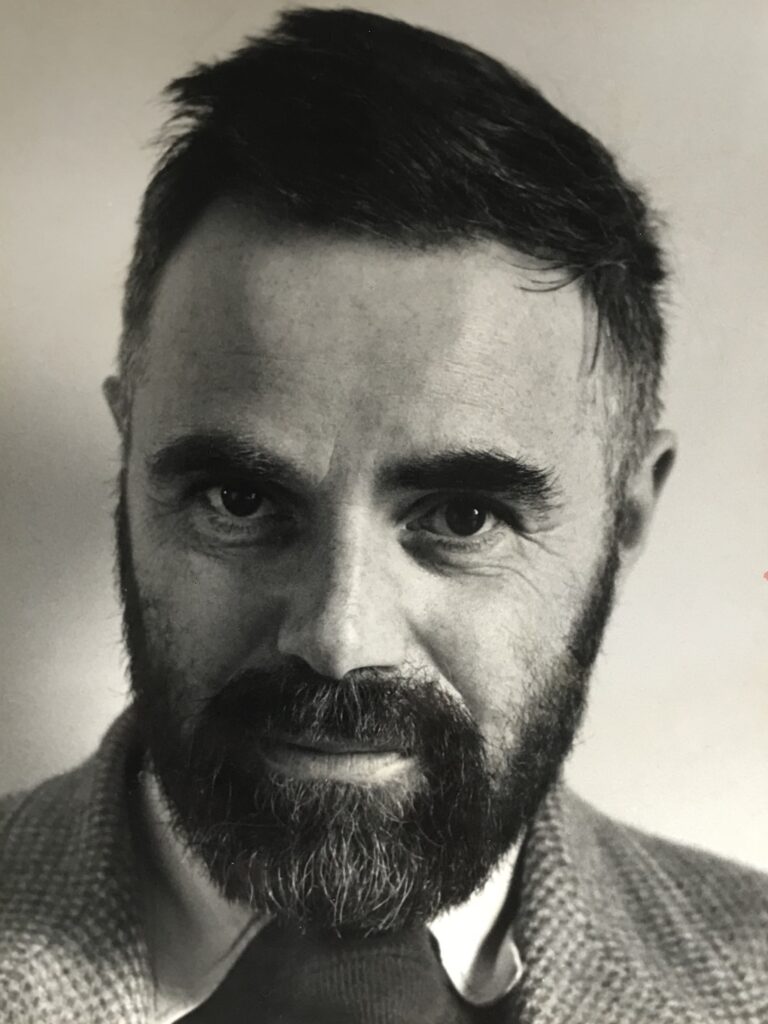

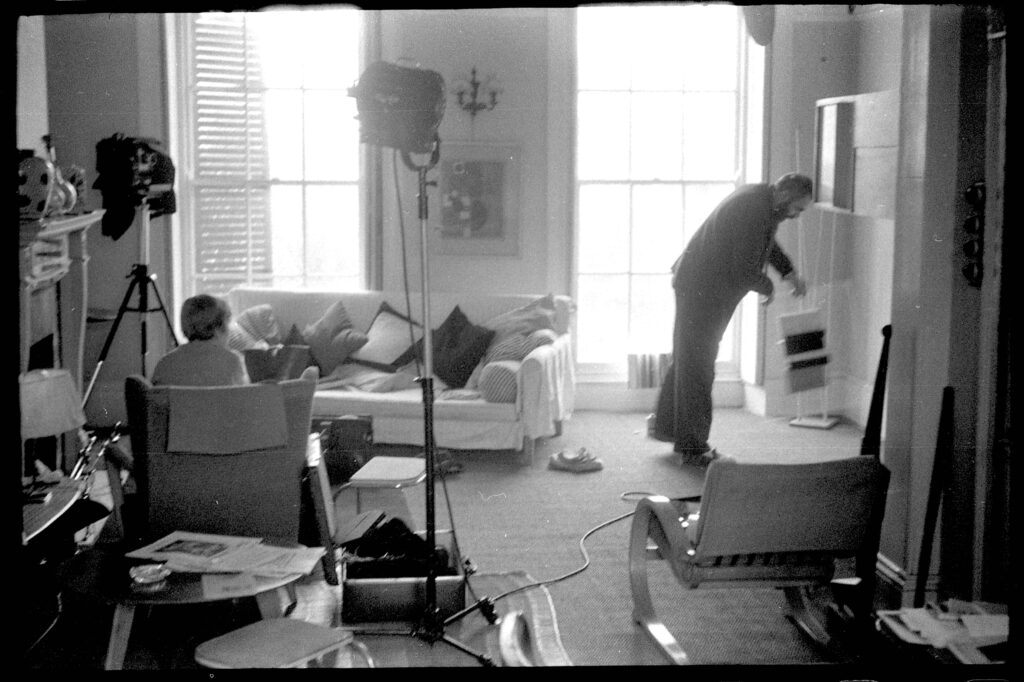

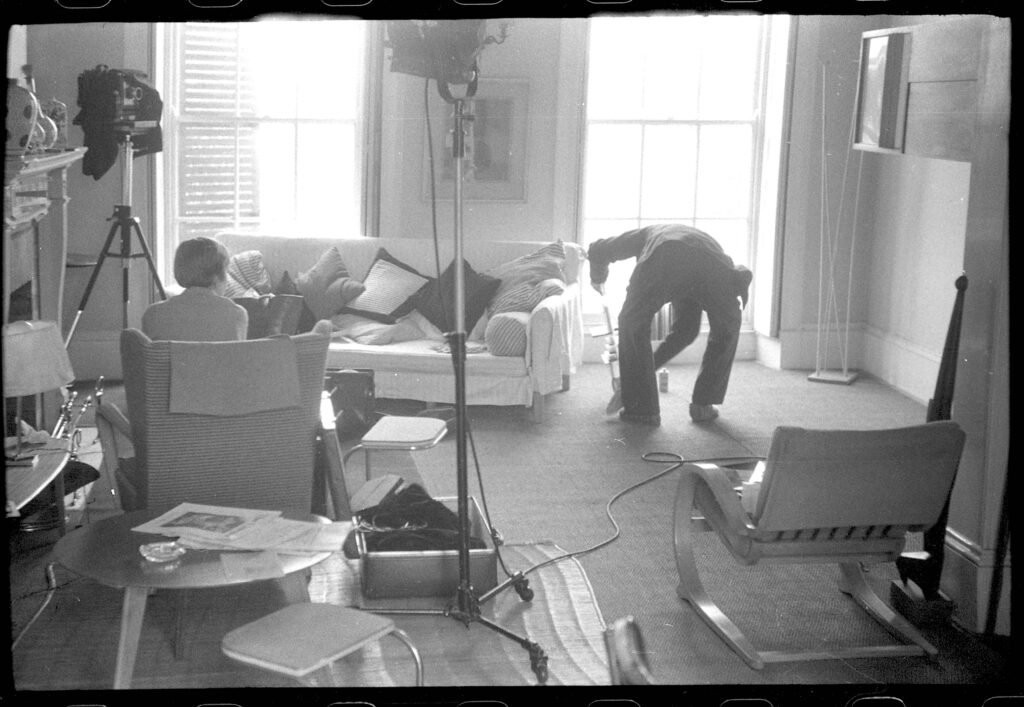

One transparency shows Pasmore, dark-haired, bearded and wearing a grey suit, seated in an armchair, with three plates on a bookcase behind him. Decorated with bold abstract patterns by the artist, the plates evoke a Japanese aesthetic, as does the accompanying branch of cherry blossom, in a glass vase. [The flowering blossom suggests this photograph was taken in March.] Although a picture rail is visible in some of these photographs, Pasmore subsequently removed this architectural feature, to create more of a white cube. The sitting room was furnished with a white couch, vases on the chimneypiece and louvered shutters outside the windows.

Three weeks after Flowers’ first visit, Pasmore wrote to him from Newcastle, requesting a photograph for a forthcoming article in Art and Architecture magazine. [Victor Pasmore, 46 Eldon Place, Newcastle on Tyne, to Adrian Flowers, 25 Jan 1956 (AF archive)].

By 1956, Pasmore had been head of fine art at Newcastle on Tyne for two years, but commuted regularly back to his Blackheath home and studio. In another Flowers photograph, he looks through a transparent section in one of his abstract reliefs. Suspended from a piano wire, this work cantilevered out from the wall. Behind it is the relief Abstract in White, Black, Indian and Lilac, a work now in the Tate (where it is dated 1957, but may date from the previous year). As the photography progressed, Pasmore hung a selection of Perspex and wood reliefs in different combinations on the sitting room wall.

Photograph by Adrian Flowers

The room was on its way to becoming a gesamkunstwerk, with abstract constructions, painted chimneypiece, striped cushions, and hanging mobile sculptures. The furniture is mid-twentieth century Modernist, including what appears to be an early Poang chair, and a wingback armchair. The modernist couch is a Hille design, from Heals. Like Pasmore, Hille’s principal designer, Robin Day, had worked on the 1951 Festival of Britain; his seating in the Royal Festival Hall was a triumph of modernist design.

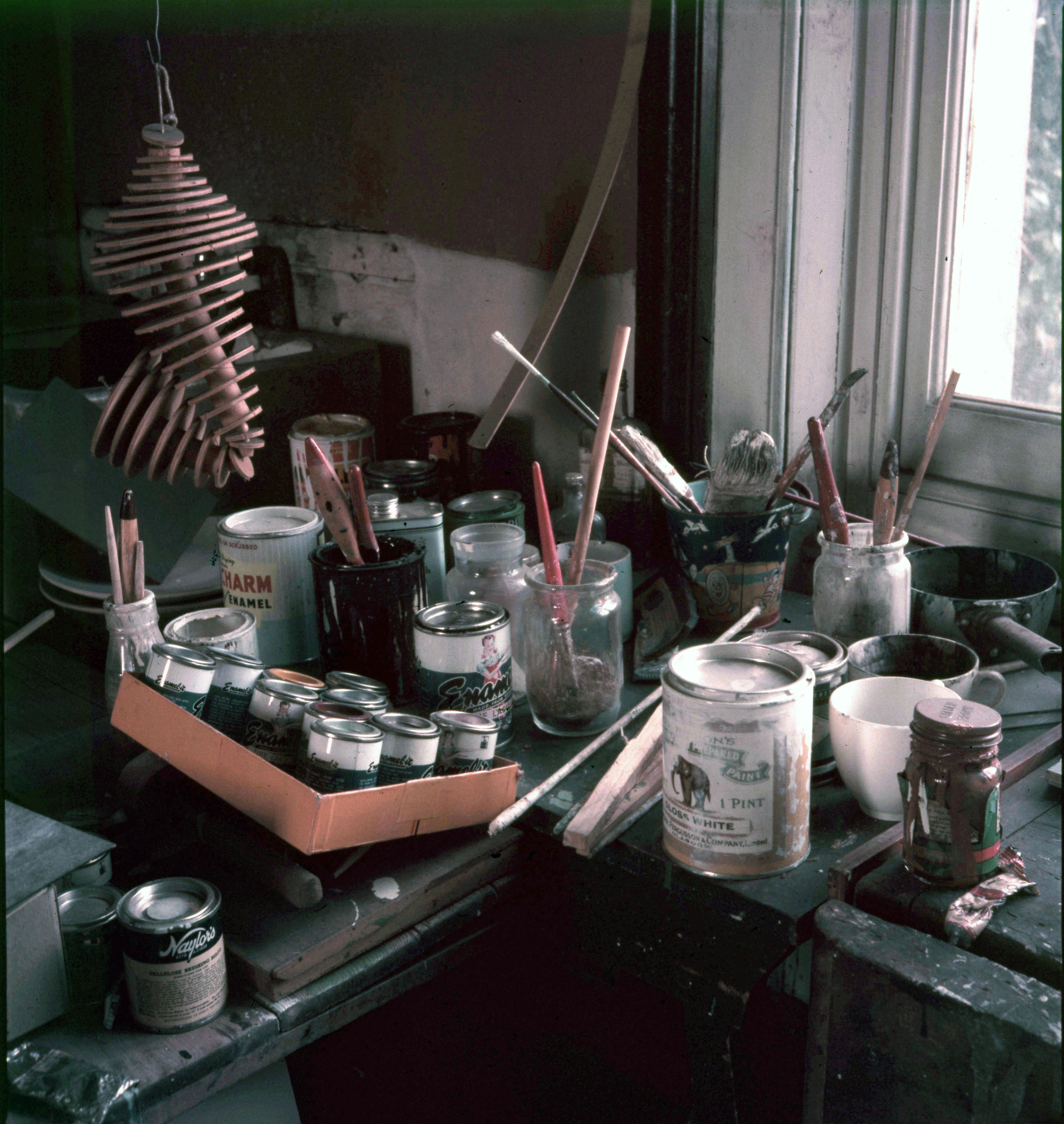

Flowers’ photograph of the studio work table at Blackheath reveals that Pasmore used household enamels to paint his perspex and wood abstract relief constructions, his preferred brand being Enamel-it. According to the label on the tin, this lacquer paint was made ‘from bakelite’. There was also Fergusson’s gloss enamel, some pigments and oil colours, and a tin of Naylor’s cellulose, used as a thinner. The brushes were a mixture of those used by fine artists and house decorators. A sculpture made of wooden spools and discs threaded onto a cord, hung over the studio work table.

Photograph by Adrian Flowers

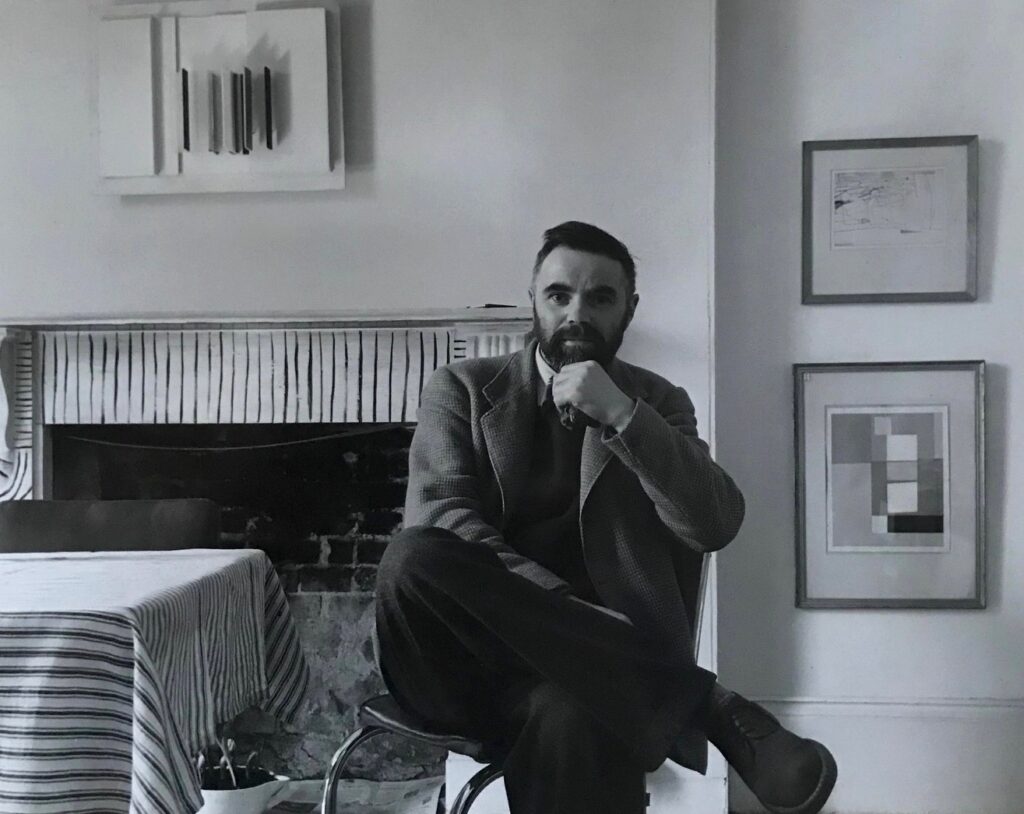

In another image, Pasmore is sitting on a metal chair, in front of a fireplace, above which hangs an abstract relief. Other geometric artworks hang on the wall alongside the fireplace. In making these works Pasmore had been influenced by American artist Charles Biederman’s book Letters on the New Art (1951) which advocated the use of industrial materials. The photographs show Pasmore during a period when he was at the peak of his career, a confident artist, thoughtful and reflective.

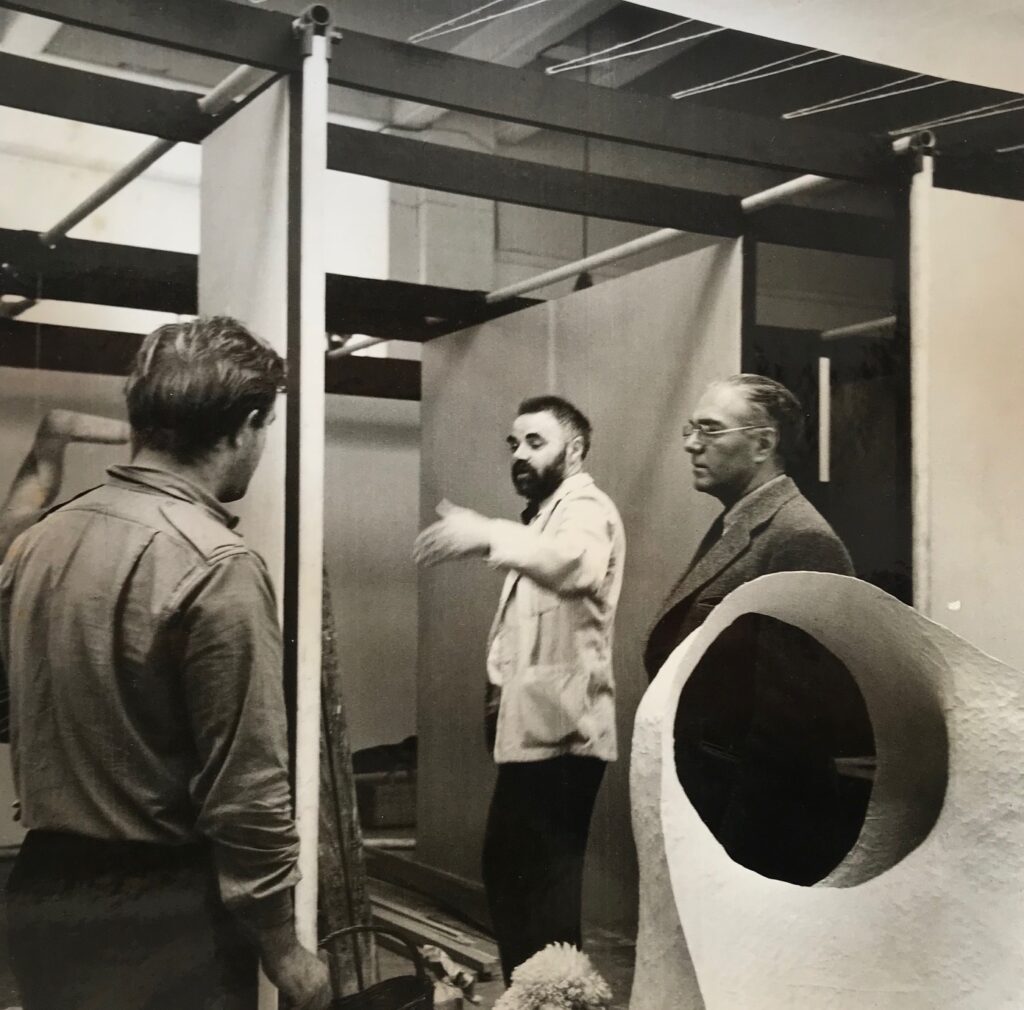

Other photographs taken by Flowers at a later date, black and white this time, show Pasmore supervising the construction of a temporary exhibition pavilion at the Whitechapel Art Gallery for the exhibition This is Tomorrow in 1956, a collaboration with Helen Phillips and Ernö Goldfinger, in which temporary walls were constructed within the gallery space using a framework of metal tubing and wood, to create an ‘environment’.

The foreground of this photograph features a section of the ‘bubble sculpture’ by

Group Eight: James Stirling, Michael Pine, Richard Matthews.

Adrian Heath on the left and Ernö Goldfinger on the right.

Photograph by Adrian Flowers

Through a lifetime of teaching, designing structures and making art, Victor Pasmore was responsible for leading a wider popular acceptance of Modernist art and architecture in mid-twentieth century Britain. Born in Surrey, he grew up in a middle class household, his mother being a painter, while his father, the medical superintendent at Croydon Mental Hospital, was a keen art collector. Pasmore attended Harrow School, where he was taught by Maurice Clarke and, three years in succession, won the Yates Thompson Prize for art. However the death of his father in 1927 resulted in Pasmore having to secure a job with London County Council. Employed as a clerk in the Public Health Department for ten years, he maintained his art education, taking evening classes at the Central School of Art. Pasmore’s work during this period was sensitive, naturalistic, and inspired by a feeling for nature and respect for artists such as Cézanne and JMW Turner. In 1934 his first exhibition took place, at the Zwemmer Gallery in London. Three years later, along with William Coldstream and Claude Rogers, he founded an independent School of Drawing and Painting at Fitzroy Street. With support and encouragement from the art historian Kenneth Clark and philanthropist Samuel Courtauld, this enterprise later became the Euston Road School. Aided by Clark, Pasmore retired from his job with LCC and became a full-time artist. During the Second World War, Pasmore was a conscientious objector, and with some difficulty succeeded, again with help from Clark and Coldstream, in obtaining exemption from military service. In 1943 he took up a teaching post at Camberwell School of Art, where he taught for six years, and was tutor to Terry Frost. During this time, while living at Chiswick, and later at Hammersmith Terrace, and inspired by Turner’s atmospheric paintings, he produced lyrical views of the river Thames.

In 1948, shortly after moving to the house at Blackheath, Pasmore shifted from painting in a lyrical representational style to one of pure abstraction. He described these works in terms suited to music—as motifs or variations—and was not afraid of what he called ‘arbitrary invention’, although his approach to creativity was in fact highly-skilled and far from arbitrary. A visit to St. Ives in 1950 and meeting with Ben Nicholson were critical to his change in approach, and the following year Pasmore was elected to the Penwith Society of Arts. As with many of his generation, he was idealistic, seeing in art a way towards a better future for society, and actively sought to share his aesthetic feelings with a wider public. In 1950 he was commissioned to create a mural for a bus station in Kingston Upon Thames, and the following year was one of the artists selected by the Arts Council to create works for the Festival of Britain. He also took up a post at the Central School of Art, where he taught for four years. In 1954 Pasmore became head of painting at the Department of Fine Art in Durham University in Newcastle, a position he held for seven years. Teaching at Newcastle provided him with the opportunity of introducing a fine art course modelled on Bauhaus teaching. This course led to a BA degree, one of the earliest in Britain or Ireland. In spite of differing approaches to art, Pasmore and Richard Hamilton worked well together. Pasmore introduced Hamilton into the school as a tutor, and in time the new arrival took over as head of department. Together, these two artists epitomise the best and most progressive art of post-war Britain, creating an energy that in every way matched that of the leading art schools of London. Commissioned to create murals for the Newcastle Civic Centre and Pilkington’s glass works, Pasmore also worked on the Peterlee development, designing a monumental Modernist concrete structure for the new town centre. In 1959, he was selected for Documenta II and two years later represented Britain at the Venice Biennale. He was also appointed a Trustee of the Tate Gallery. In 1966 Pasmore bought a house in Malta, and over the following years, until his death, spent much of his time there. His son John kept on the house at Blackheath, with the studio and other rooms virtually unchanged since the January day in 1956 when Adrian Flowers recorded his first images of Pasmore on film.

Text: Peter Murray

Editor: Francesca Flowers

All images subject to copyright

Adrian Flowers Archive ©