Job No. 6482

28th November – 3rd December 1969 Beethoven

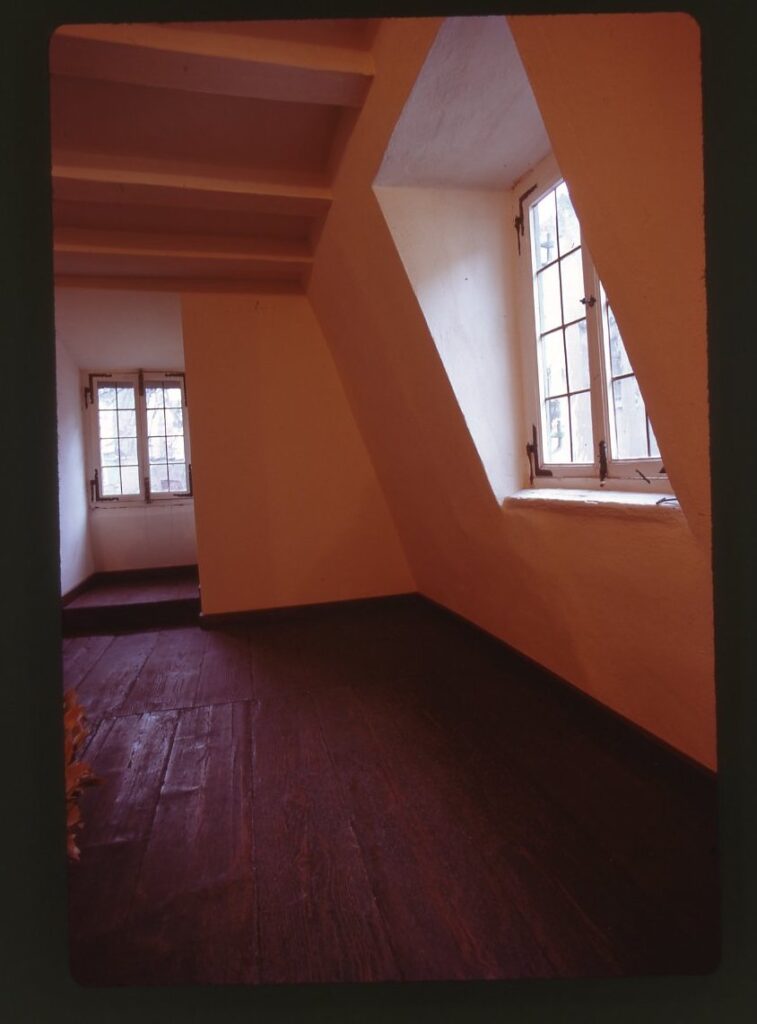

In late November 1969, at the request of the Observer magazine, Adrian Flowers travelled to Bonn, and then to Vienna, photographing places and artefacts associated with Ludwig van Beethoven, whose bi-centenary would fall the following year. In Bonn, Flowers went to the “Beethovens Gerburtshaus” at No. 20 Bonngasse, where on 16th December 1770 the composer was born. One of the few old buildings to survive in the city, this eighteenth-century Baroque house now houses a museum, the Beethoven-Haus. When Flowers visited, it was not only a photographer’s eye that drew him to some of the key exhibits, but also a sensitive response to the frustrations of Beethoven, who was forced to use ear trumpets, and to pound the piano keyboard, in an attempt to overcome his deafness. The photographs taken by him evoke in a powerful way what Beethoven must have suffered, as this condition made it almost impossible for the composer to hear his own playing of the piano or violin.

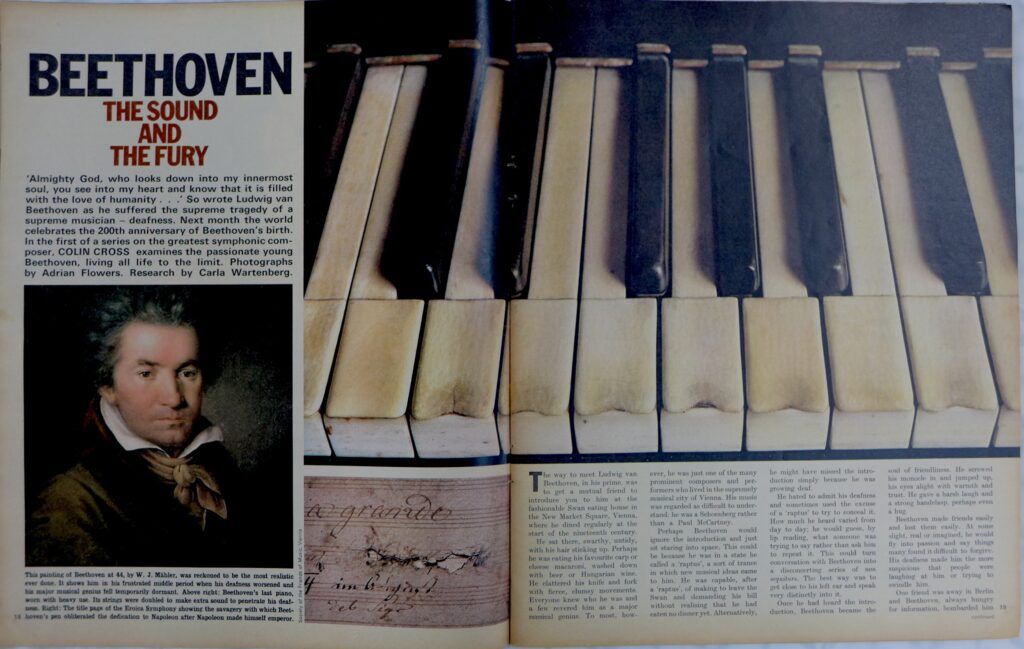

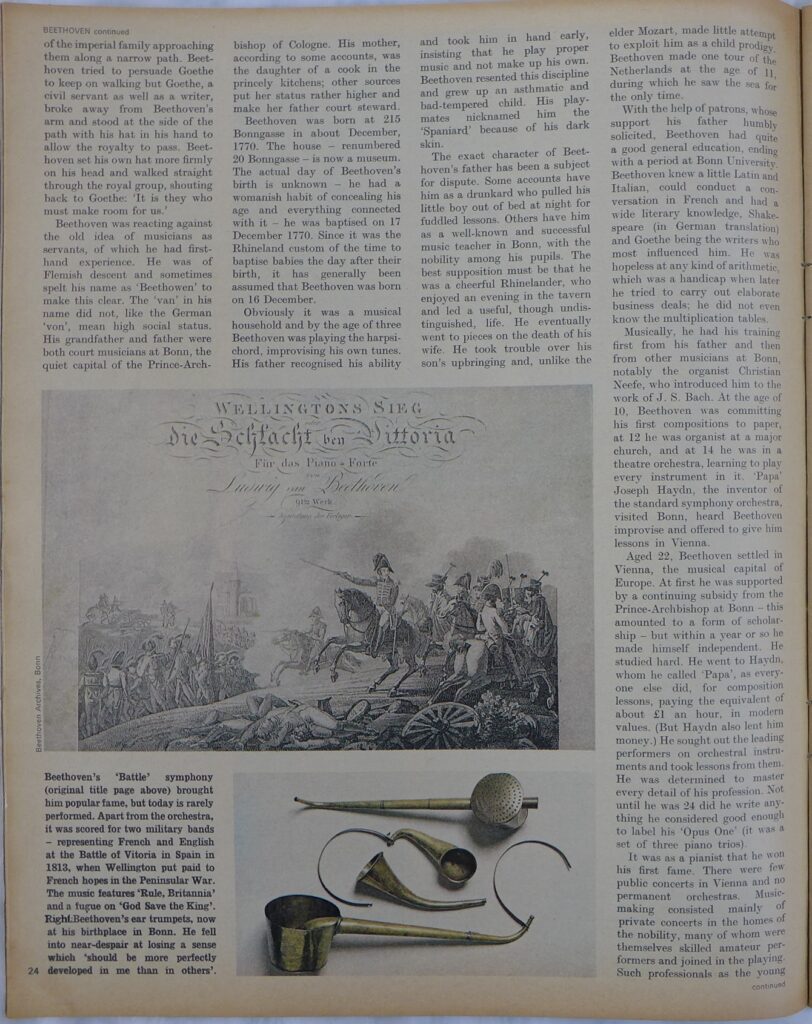

The grand piano at No. 20 Bonngasse is one of three—and the last—played by Beethoven. Made in Vienna by instrument maker Conrad Graf (1782-1851), it was loaned to the composer in 1826. Judging by the condition of the ivory keys today, it is tempting to envision Beethoven wearing them out with his heavy playing. The ivories have evidently been replaced on at least one occasion, then worn down again, like nails bitten to the quick—an image captured in one of Flowers’ most expressive photographs. With its label ‘L. van Beethofen”, the piano could be read as a testament to the frustrations experienced by the composer. However this is probably a romantic notion, as the composer died in 1827 and the Graf piano has been played many times since then, by other musicians. The ear trumpets and acoustic instruments, also photographed by Flowers, provide more telling evidence of the composer’s deafness. They were made for Beethoven by Johann Nepomunk Mälzel, a Czech inventor who also invented the metronome.

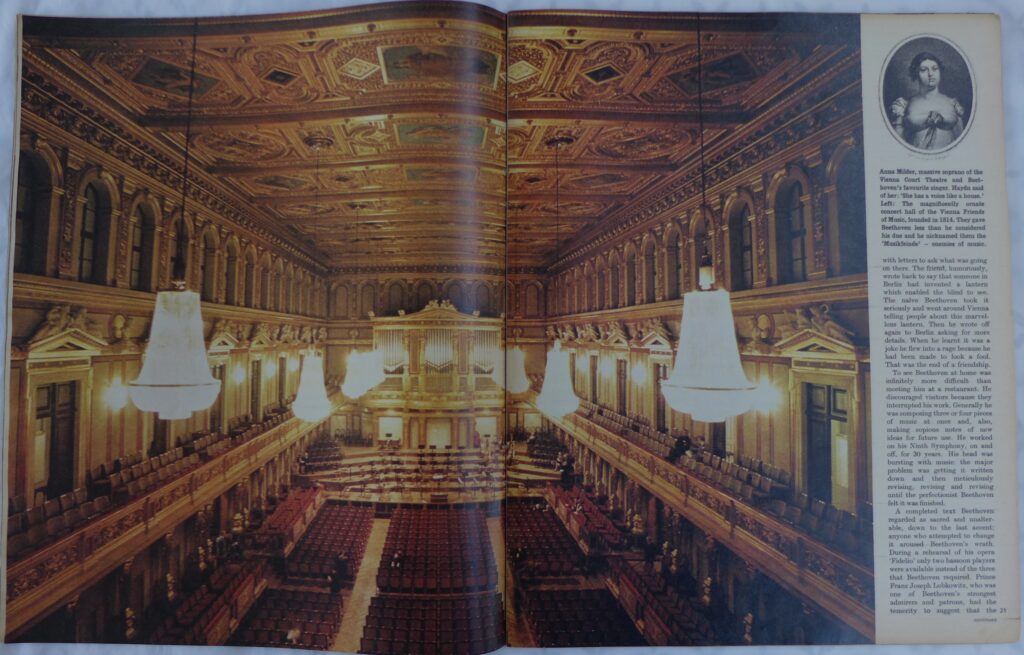

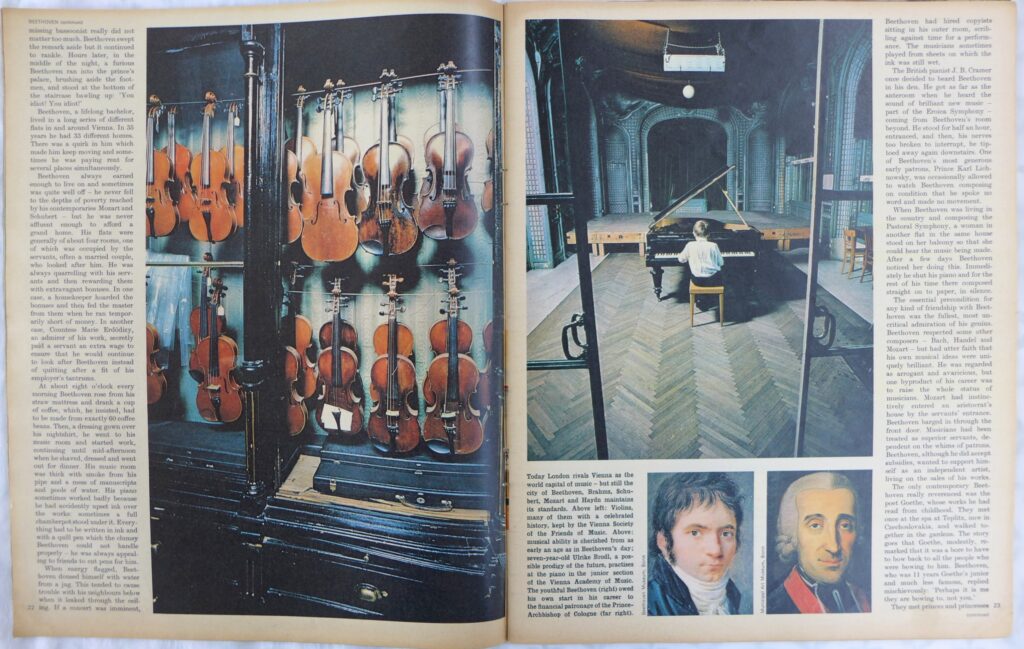

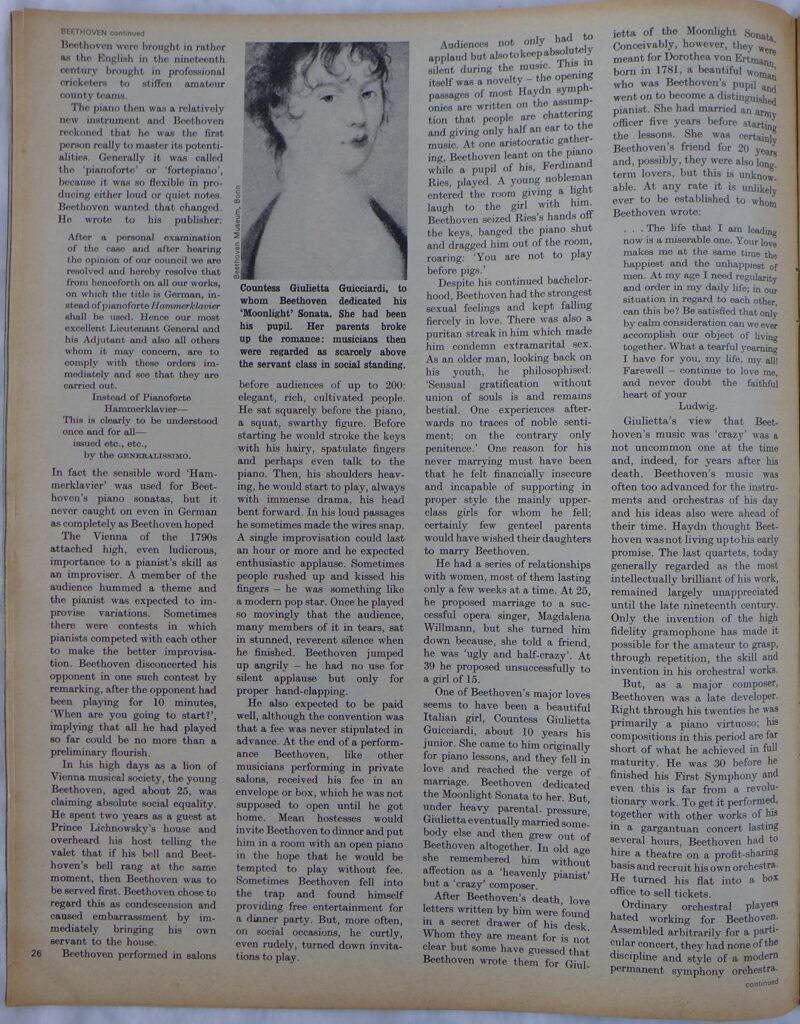

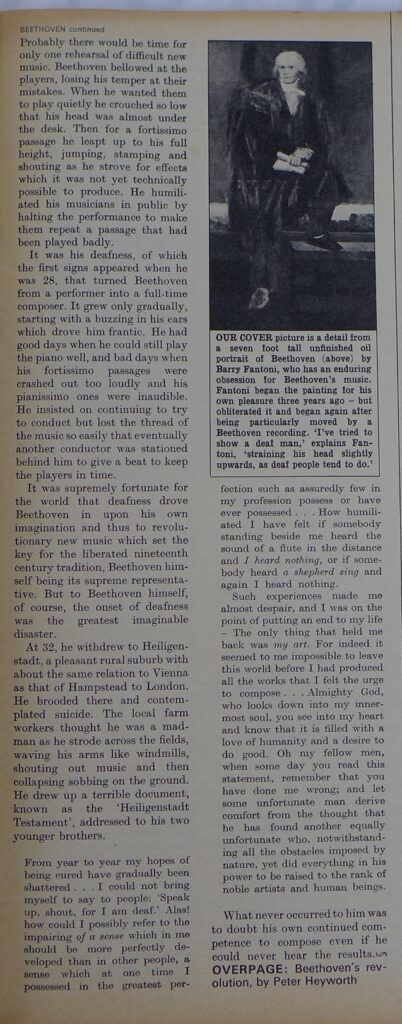

Flowers’ photographs of piano and artefacts appeared a year later, in an article written by Colin Cross and published in the Observer magazine on 29th November 1970. Other photographs by Flowers that accompanied the article include an interior view of the ornate concert hall of the Vienna Friends of Music, founded in 1814. The Friends were so mean-spirited in paying Beethoven that he nicknamed them the ‘Musikfiend’, or enemies of music. Nevertheless, they were friendly enough to allow Flowers to photograph their collection of historic violins. He also visited the Vienna Academy of Music, photographing seven year-old Ulrike Brodl practising the piano. Sadly, the hopes expressed by the Observer in 1969, that Brodl would become a prodigy, appear not to have been borne out. The article was illustrated also with a photograph by Flowers of the autograph score for Symphony No. 3, the “Eroica”. This had been dedicated in 1803 to the composer’s hero Napoleon, but when the latter crowned himself Emperor—a political act that infuriated Beethoven—the composer scratched out the dedication with the nib of his quill pen, lamenting “Is he then, too, nothing more an ordinary human being?” The repudiation seemed complete (and its mythologizing certainly was) until Napoleon’s brother Jerome, crowned king of Westphalia, asked Beethoven to become court composer, a move thwarted by patrons in Vienna, who paid him to remain in the Austrian capital.

Other photographs that are preserved in the AF Archive, but did not appear in the 1970 Observer article, include the exterior of No. 20 Bonngasse, the attic bedroom where Beethoven was born, autograph scores, a pencil sketch of the composer by August von Kloeber, a 1905 bronze bust by Russian-born sculptor Naoum Aronson, in the museum garden, and a detail of the bronze monument, sculpted by Caspar von Zumbusch in 1880, in Beethovenplatz in Vienna.

In another article in that same issue of the Observer magazine, Peter Heyworth wrote about Beethoven: “Like most men of his age (he was born the same year as Wordsworth), he was generally sympathetic to the ideals of 1789, liked to consider himself a democrat and cultivated a gruff egalitarian manner that shocked the courtier in Goethe, born a crucial 21 years earlier. . . Until disillusionment set in, he regarded Napoleon as the liberator of mankind, and if that sounds naïve, it pales before the eulogies heaped on Stalin’s head by British intellectuals in the days of the Popular Front.” In the British cultural world of the early 1970’s, Beethoven occupied an uneasy place, admired for his musical genius but suspect because of his pan-European credentials and Promethean undertones. In A Clockwork Orange (1971), a film based on Anthony Burgess’s novel, the protagonist Alex, subjected to aversion therapy, complains “I wake up. The pain and sickness all over me like an animal. Then I realised what it was. The music coming up from the floor was our old friend, Ludwig Van, and the dreaded Ninth Symphony”. In A Clockwork Orange, a direct link is drawn between Beethoven’s music and anarchic violence and terror. In 2019, for different, but perhaps related, reasons, a group of 29 British MEP’s turned their backs when his Ode to Joy, an extract from the Ninth Symphony and the anthem of the European Union, was played at the Parliament in Strasbourg. With the 250th anniversary of the composer’s birth now being celebrated, half a century after Flowers visited Bonn and Vienna, his photographs are as visually eloquent today, as they were then.

Text: Peter Murray

Editor & publisher: Francesca Flowers

All images subject to copyright

Adrian Flowers Archive ©