1890 – 1956

On 7th July 1955, Adrian and Angela Flowers visited the artist Nina Hamnett in her London flat. The photographs Adrian took that evening are among the last visual records of this legendary ‘Queen of Bohemia’. Seated on her bed, Hamnett held forth for her visitors, recounting tales of her life as an artist in Edwardian London and Paris. Cheerful, ravaged, her face like that of an weather-beaten mariner, Hamnett sat, her crutches on the bed beside her. Also on the bed sat a man wearing a vest and smoking a cigarette, his expression thoughtful and pensive. Angela remembers him as a merchant seaman, a friend of Nina’s. There was also a young woman, a journalist. The photographs capture details of Hamnett’s home life, and her love of books and art; above the fireplace were stacked shelves of books, with paintings propped against the wall. A framed drawing of a classical head may have been the same student work for which Hamnett had been awarded a prize, half a century before, at the Portsmouth School of Art. A single candle, on a small footstool beside the fireplace, was likely the only source of illumination when the electricity meter ran out.

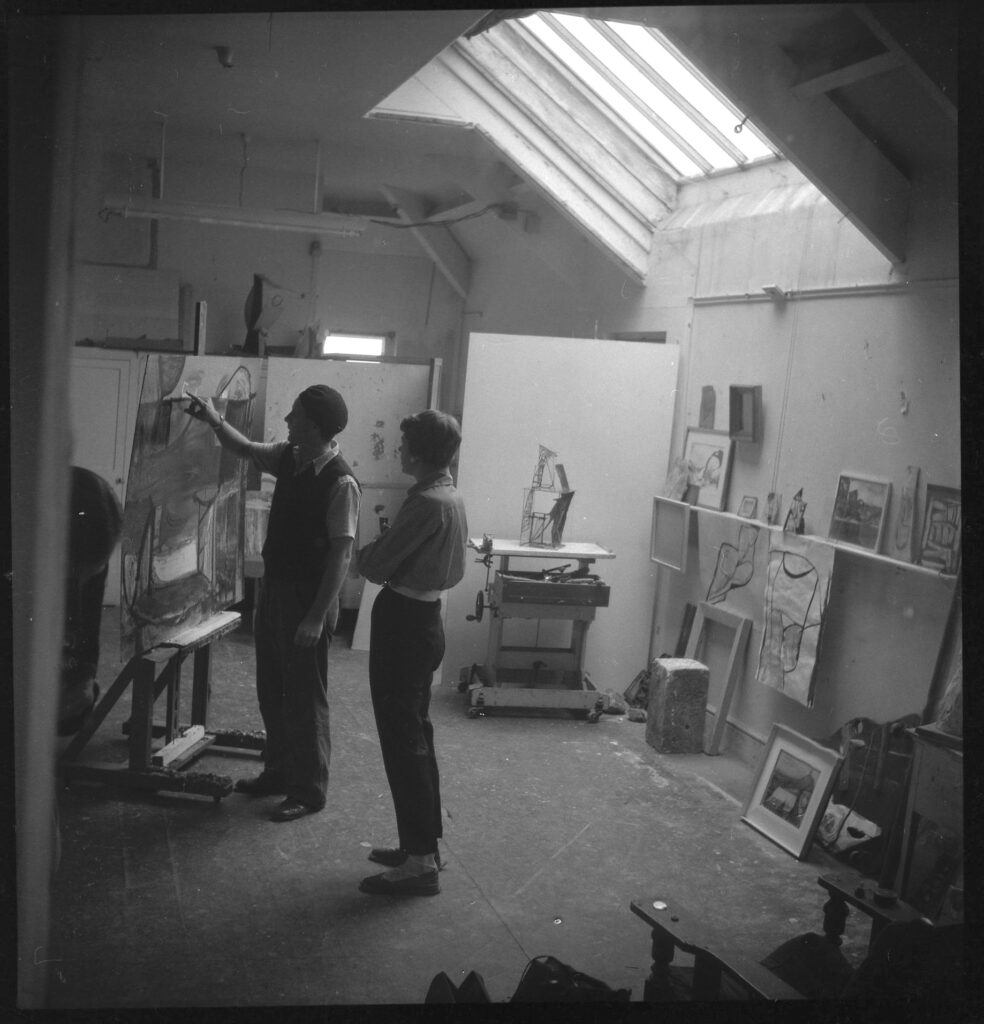

Photograph by Adrian Flowers

In 1955, Hamnett’s second book of memoirs, Is She a Lady?, had just been published, and she was enjoying her time in the limelight. Other photographs taken by Flowers, either on that day or close to it, show her sitting at a bar, with Angela, and also talking to others around her. However, Hamnett’s recollections of her own life were often embellished for literary effect. She told different versions of the same story, and invented episodes, to increase the dramatic effect. She was clearly delighted with the photography session, and dressed up for the occasion.

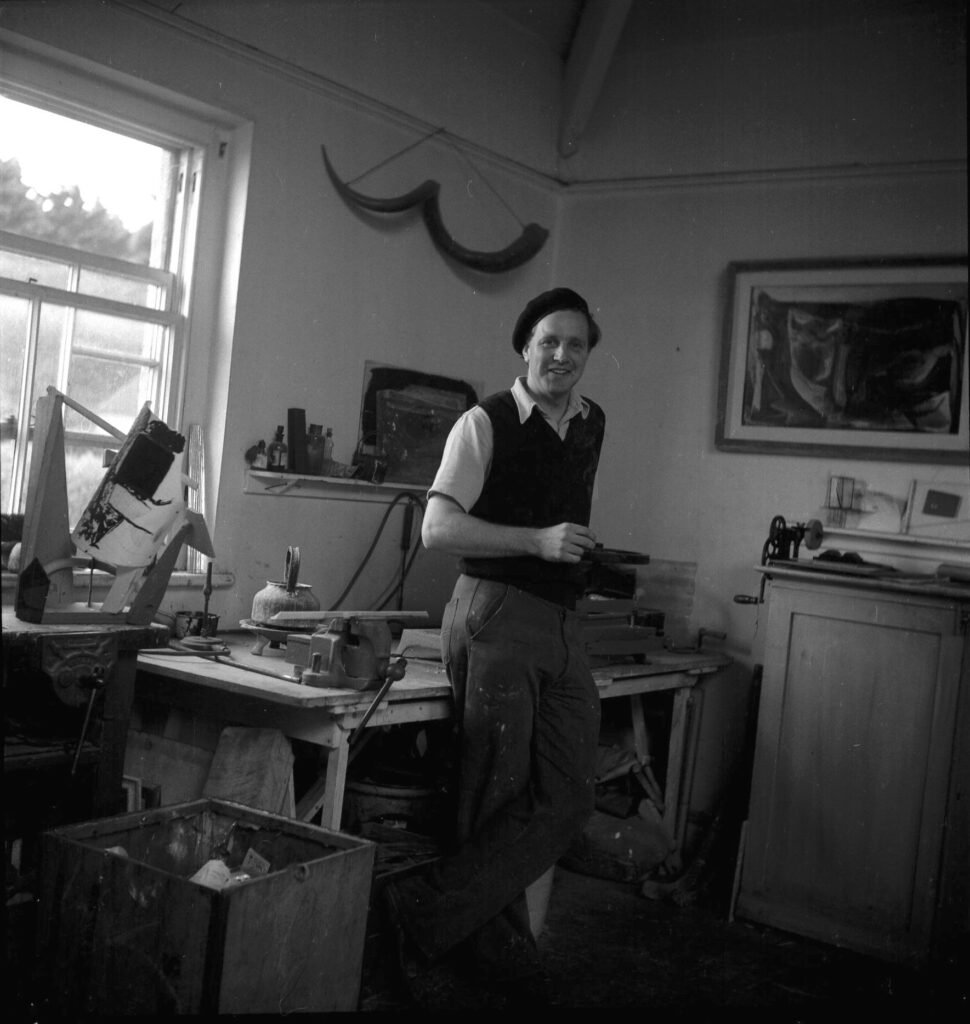

Photograph by Adrian Flowers

Angela recalls the visit to the bar as having taken place at Little Venice, just north of Paddington Station. The bar was probably in the Bridge House, at Delamere Terrace, close to the Regent’s Canal bridge, an ironwork structure that appears in a 1947 watercolour by Hamnett. In 2019, Kate Thorogood curated an exhibition of Nina Hamnet’s work at the Fitzrovia Chapel, in the course of which she debunked some mythologies, principally the story that Hamnett died in a fall from her flat in Fitzrovia. In fact, Hamnett appears to have moved to Paddington some years earlier: “It is understood that in 1947, there was a fire in her block of flats from which a girl tried to escape by leaping out of the window, only to be impaled on the railings below. Later, Nina would hear this story being told as if she were the one who tragically died. Having been made homeless by the fire and by all accounts refused a place in Marylebone Workhouse, Nina was rehoused in Paddington, not Fitzrovia. It was here she died, also from a fall out of a window. There are many versions of the story of her death, including some in which she dies impaled on the railings. Some claim there was a drunken stumble; others a suicide attempt.” At the time of the Flowers’ visit, Hamnett was just sixty-five, but she was destined to live for just one more year. In 1956, several days after the fall—which was probably accidental—she died in hospital.

Although her death took place in tragic circumstances, Hamnett remains alive in the minds and memories of many, both as a cultural inspiration and a cautionary tale. The story of her life has a stellar quality, but a desire to be the centre of attention led her to forego her own talents as an artist, and to instead become model, dancer, companion, and lover and muse to others, while neglecting her own creative work. Born in 1890, a rackety childhood in Tenby with a grandmother, a couple of years in Ireland with an improvident military father, and teenage forays into London’s bohemia had ill-prepared Hamnett for the conventional career expected of her, of completing a secretarial course, becoming a typist, and settling into suburban life. Having studied at the Metropolitan School in Dublin, then Portsmouth, then the London School of Art, she far preferred the company of sculptors, painters and writers, and, with her hair cut page-boy style and wearing brightly-patterned clothes, enjoyed being stared at by passers-by on the Tottenham Court Road.

In 1914, at the outset of the First World War, Hamnett was in Paris, hard up, but contriving to remain at the heart of the artistic world that revolved around Montparnasse and La Rotonde. She drank with Zadkine and modelled for Modigliani, in much the same way as, while in London, she had modelled for Roger Fry, Walter Sickert and Henri Gaudier-Brzeska. In Paris, she took off her clothes at parties and, in the manner of Isadora Duncan, danced with a veil, applauded as much by the older women present as by the young avant-garde artists who delighted in this expression of artistic freedom. Although she had male lovers, Hamnett’s friendships with women were often more important to her. She married the Norwegian artist Edgar de Bergen (Roald Kristian) in 1914, but having brought him to England found he was a bore, and was not overly dismayed when he failed to register and was deported back to the Continent as an ‘undesirable alien’. Hamnett then threw herself into the artistic life of London with gusto, dining with Augustus John at the Tour Eiffel restaurant, sketching George Moore and Lord Alfred Douglas at the Café Royal, and working with Roger Fry at the Omega Workshops. In 1917-18 she taught at the Westminster School of Art, and her portraits from these years are among her best. In the 1920’s she moved back to Paris and re-joined the avant-garde, counting Cocteau, Stravinsky and Eric Satie among her friends. These were Hamnett’s most productive years, and she travelled back to London several times to attend openings of exhibitions of her paintings. Two volumes of autobiography preserve the outline, if not the emotional form, of these intense years; published in 1932, Laughing Torso is a window into the avant-garde art worlds of Paris and London, while twenty-three years later, Is She a Lady? brought readers up to date on her spiced-up adventures. Like many of her generation, the First World War had cast a long shadow over Hamnett’s life, and the onset of a second war in 1939 meant that again she could not travel to Paris, and so, over the following two decades, she continued with her bohemian life, holding court at the Fitzroy Tavern in Soho. With alcohol gradually replacing painting, she acquired notoriety, while her friends, in time, disappeared, to be replaced by drinking companions, who to a greater or lesser degree abetted her in this fall from grace. In her formative years, Hamnett’s father, an army officer, had been an overbearing and negative influence, fully expecting his daughter to fail in her determination to live an artistic life. After his death, she went some way towards making up for that disappointment, but remains nonetheless a compelling figure in the world of British avant-garde art.

Text: Peter Murray

Editor: Francesca Flowers

All images subject to copyright.

Adrian Flowers Archive ©