(1920 – 2018)

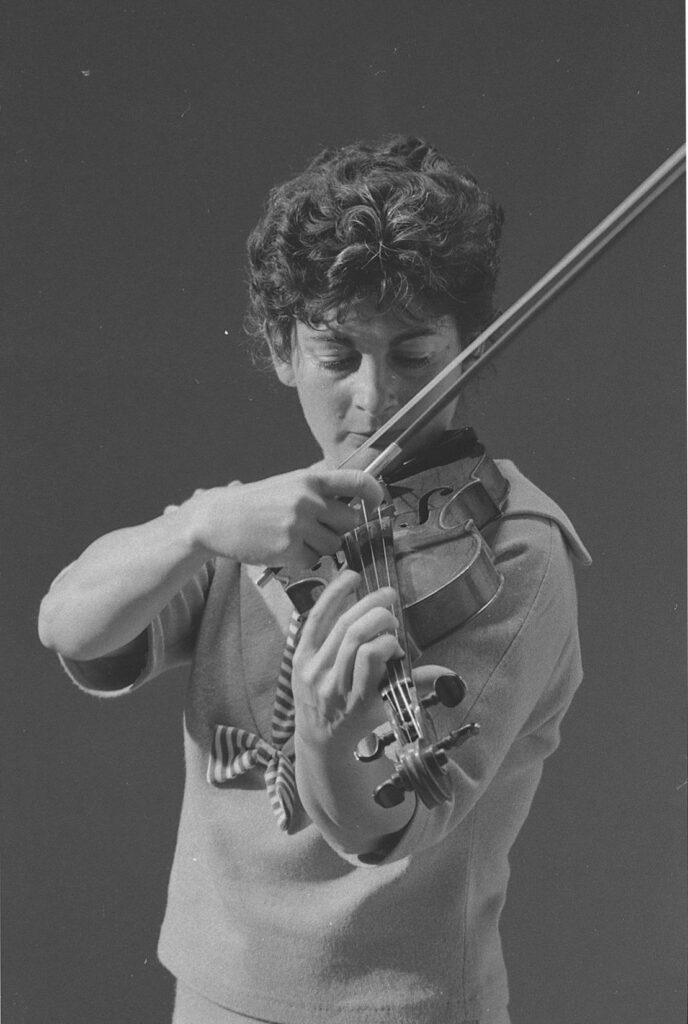

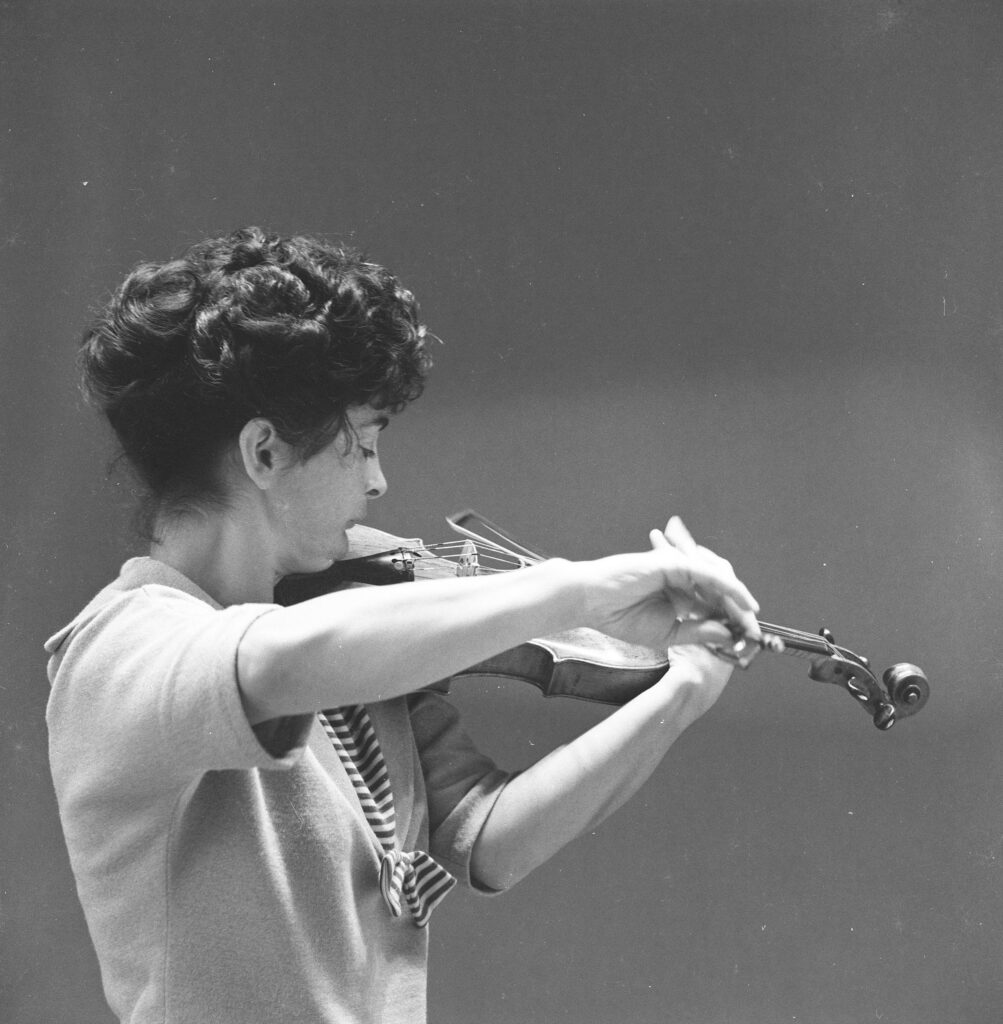

Although still in her early forties when photographed by Adrian Flowers in March 1961, Kató Havas had already gained a reputation as one of the leading violin teachers in Europe and the United States. The photographs taken by Flowers that day show Havas demonstrating her technique of playing the violin, an approach more relaxed than the traditional concert style which had carried over from the nineteenth century. In some of the portrait photographs, a dark-haired and stylishly dressed Havas, holding her violin, looks directly at the camera. Other images show her playing, bow in her right hand, and left elbow directly below the violin. This was the loose, fluid style of playing that Havas had witnessed as a child, when she saw Gypsy musicians playing in her native Carpathia, and which she developed into the technique for which she became famous.

Born in the market town of Târgu Secuiesc (Keszdivasarhely) in the Carpathian mountains, from an early age Havas’s parents, Sandor and Paula Weinberger, had encouraged her music studies, following the pedagogical system then being developed by Zoltan Kodály. In 1927, aged seven, Havas gave her first professional recital at Kolozsvár, playing works by Brahms and Schubert, and the following year enrolled at the Franz Liszt Academy in Budapest, where she studied under Imre Waldbauer. Whilst a student, she met Bartók, Kodály and Dohnányi, with all three attending her first recital at the Academy. It was during this time that the pressure of performance began to affect Havas’s playing; the rigid technique she had been taught was causing tendonitis and other physical problems. In 1939, she travelled to the United States, making her debut at Carnegie Hall, and also learning, from David Mendoza, a more natural left-hand method of violin playing.

The following year, giving her Hungarian ‘minders’ the slip, she eloped with the author William Woods. Had she returned to Hungary, she would almost certainly have been amongst the more than one hundred thousand Transylvanian Jews who were exterminated in death camps. In 1944, all the Jews of her native town Targu Sacuiesc were deported to Auschwitz. Through his writings, Woods documented a world of terror from which he had helped Kató escape: published in 1942, his debut novel Edge of Darkness documents Nazi atrocities in Norway. This was followed with Manuela (1958) a novel recounting the story of a middle-aged ship’s captain who falls in love with a young female stowaway: the film version was directed by Guy Hamilton, and starred Elsa Martinelli and Trevor Howard. Woods and Havas went on to have three daughters, Susanna, Pamela and Kate, and Havas gave up giving concert recitals, concentrating instead on developing a more natural way of playing the violin, using rhythm and song: “Hear with your eyes, and see with your left hand”, she said, emphasising that a violin player should strive to feel there was ‘no violin’ and ‘no bow hold’.

Although in 1920—the year she was born—Transylvania had been transferred from Austro-Hungarian rule to the Romanian kingdom, Havas always regarded herself as Hungarian. Unable to return to her homeland for decades because of the post-war Russian occupation, she and Woods settled in Dorset, England, where he continued his career as a screenwriter, working mainly for television. Meanwhile, Havas took up music again, teaching, writing and gaining a reputation as teacher, performer and theorist; her approach enabling many musicians to overcome stage fright, and to give more natural performances. Her first book, A New Approach to Violin Playing was published in 1961: “A warm and beautiful tone has nothing to do with talent or individual personality. It is merely the putting the right pressure, on the right pot, at the right moment.”

To achieve good results, never tell a pupil what not to do. Give her something positive to do instead. As soon as the cause of the trouble is recognized, track it down step by step with such compelling logic that there is not an atom of doubt left. Questions and discussions are to be encouraged, not only so that the pupil can work with the teacher but also to give her a chance to think things out for herself. Demonstrate: first, the incorrect way, to point out the faulty tone, and then the correct way. Results should be judged by the “degree of excellence in tone production” because the ability to listen, and listen continuously, is one of the greatest voids among young violinists (p.57).

This was followed by several publications including her 1973 Stage Fright and Freedom to Play, published in 1981. Lecturing at Oxford University and television appearances brought Havas a degree of fame. She founded and directed the Purbeck Music Festival in Dorset, as well as the Roehampton Music Festival in London, and the International Festival in Oxford. In 1971, her marriage to Woods having ended in divorce, she married Tim Millard-Tucker, a design engineer. In 1985, the “Kató Havas Association for the New Approach” was founded, and in 2002 she was invited to return to Hungary to lecture at the Academy where she had studied in the 1930’s. In 2002 she was appointed OBE. Sixteen years later, Havas died, aged 98.

She had had a worldwide influence, and among those who benefitted from her teaching were Janet Scott Hoyt, Pamela Price in Sheffield, John Ehrlich and Don Peterson in Iowa, and Claude Kenneson in the University of Alberta. For many years Claude Kenneson had taught at the Havas Summer School in Dorset, and through his writings and career he endeavoured to continue her legacy in music.

Text: Peter Murray

Editor: Francesca Flowers

All images subject to copyright.

Adrian Flowers Archive ©