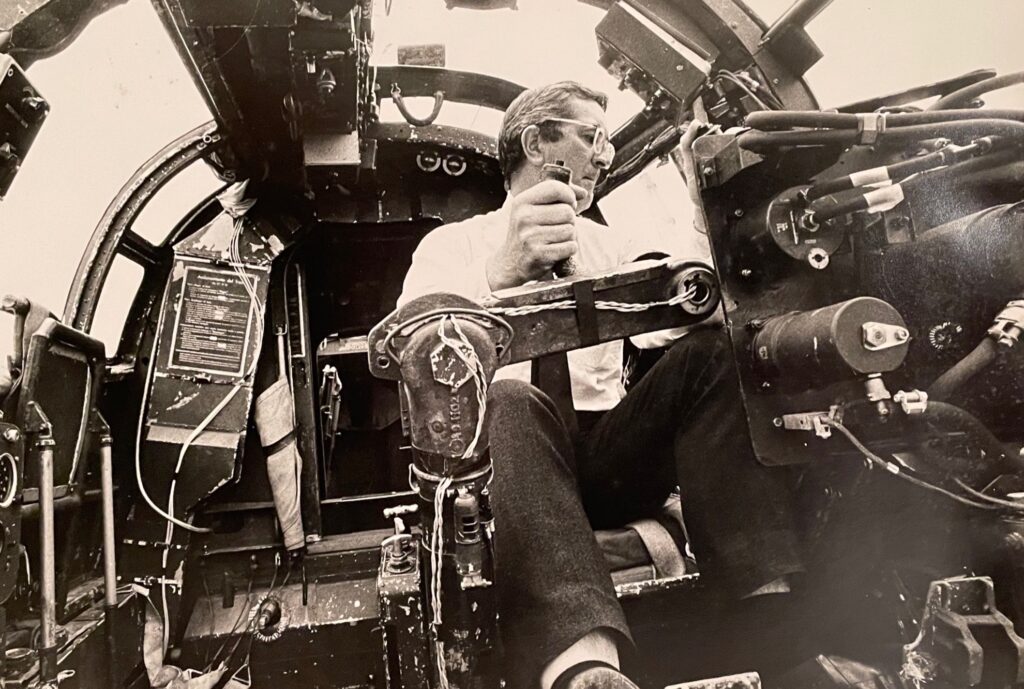

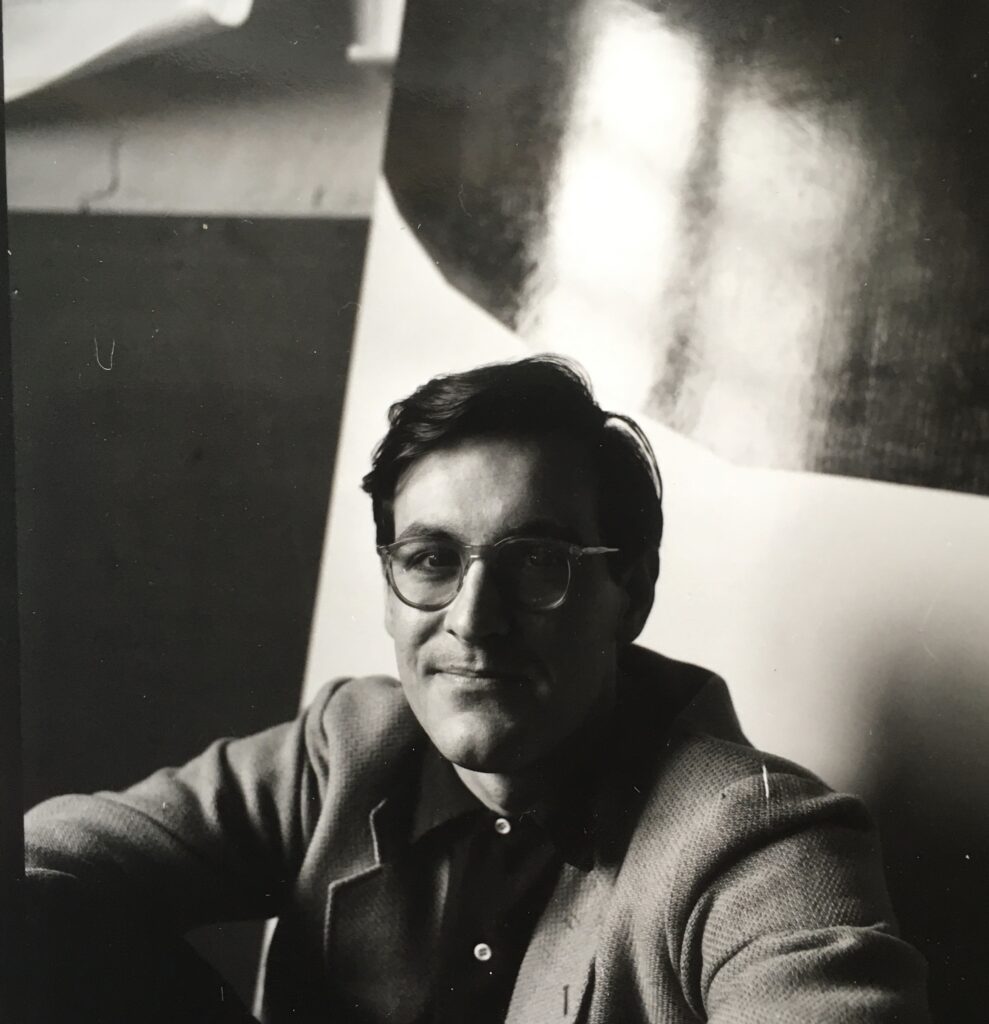

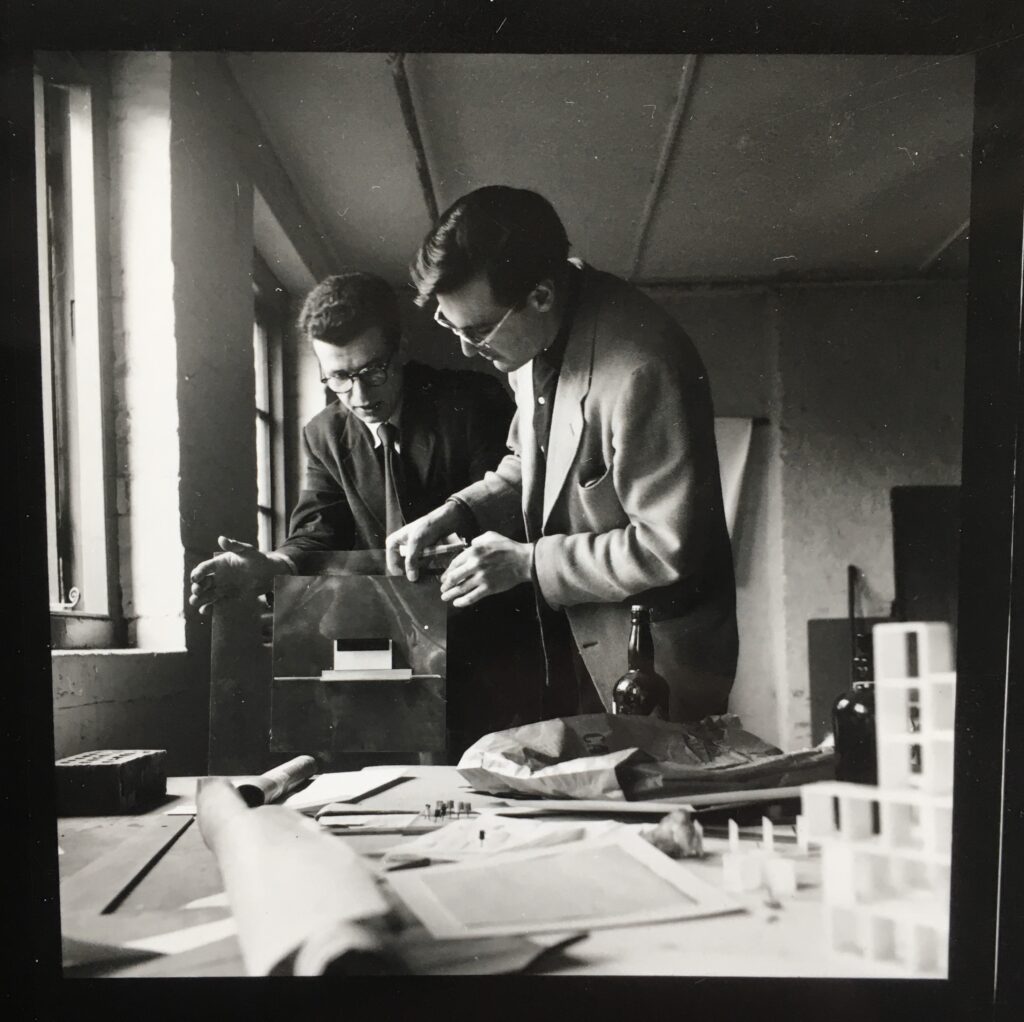

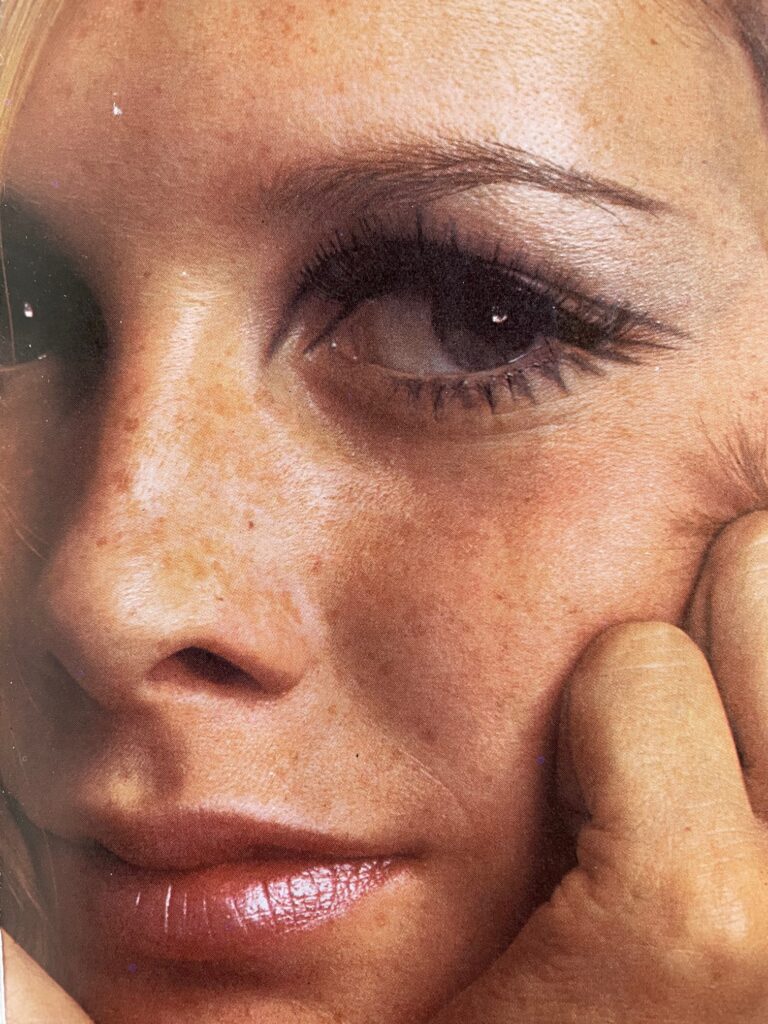

Adrian Flowers in 1966

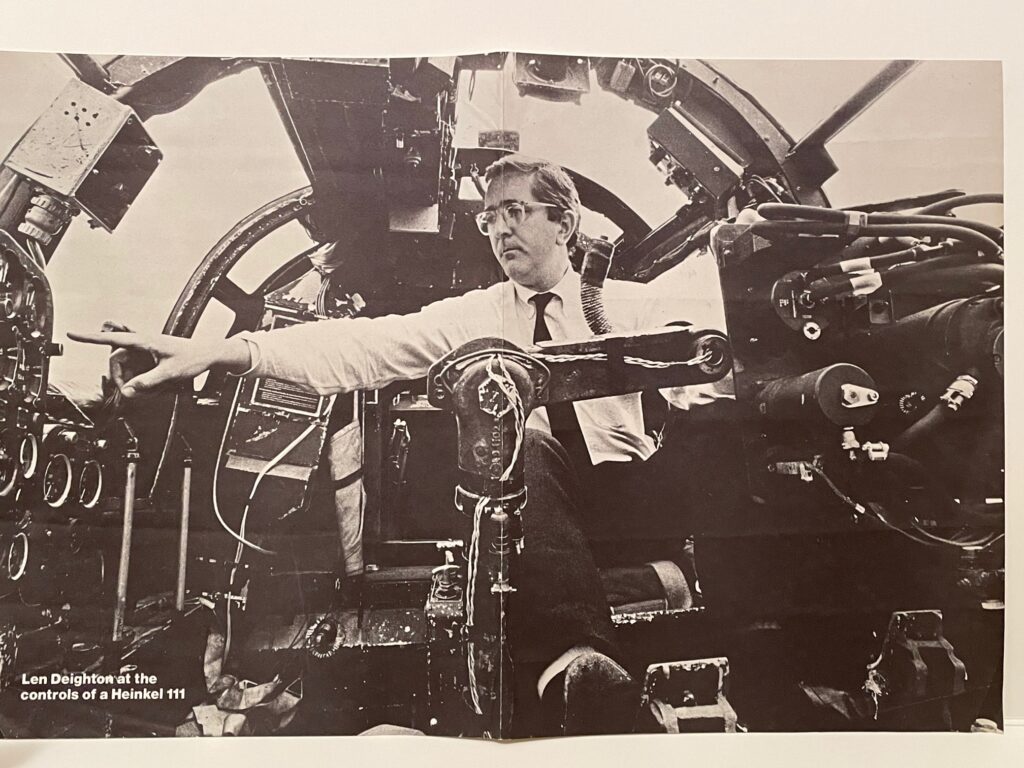

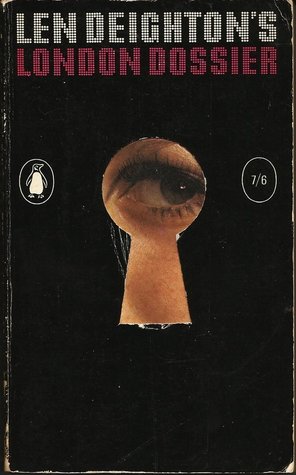

In 1967, Penguin paperbacks published the London Dossier by Len Deighton. The book comprised essays on London by people who knew the city well, including Adrian Bailey, Jane Wilson, Spike Hughes and, of course, Adrian Flowers. A brief biography, written by Deighton, introduces the chapter on photography written by Flowers, and also throws light on their friendship:

Born in the general depression, is still recovering. A typical cancerian who moves sideways out of trouble. His main occupation is advertising and editorial photography. He has taken food pictures for the Observer and took the cover photo of Twiggy for this book. His studio in Tite Street, Chelsea, is crammed full of equipment, all of which he insists is absolutely necessary. His home is in Kentish Town, where he keeps his wife, three sons, one daughter, a dog and a cat, and an au pair girl. He owns four old cars, which are shared by his assistants, and a launch for touring the Thames. Keeps fit by playing football every day with his faithful bitch, Sarah. His aim in life, apart from keeping his wife happy, is to take the picture of all time.

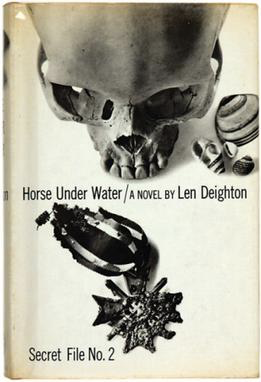

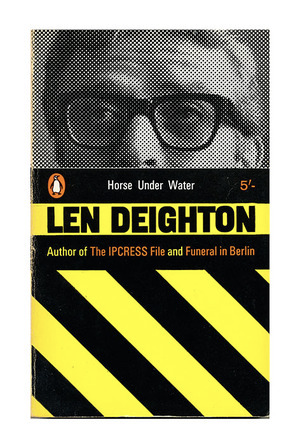

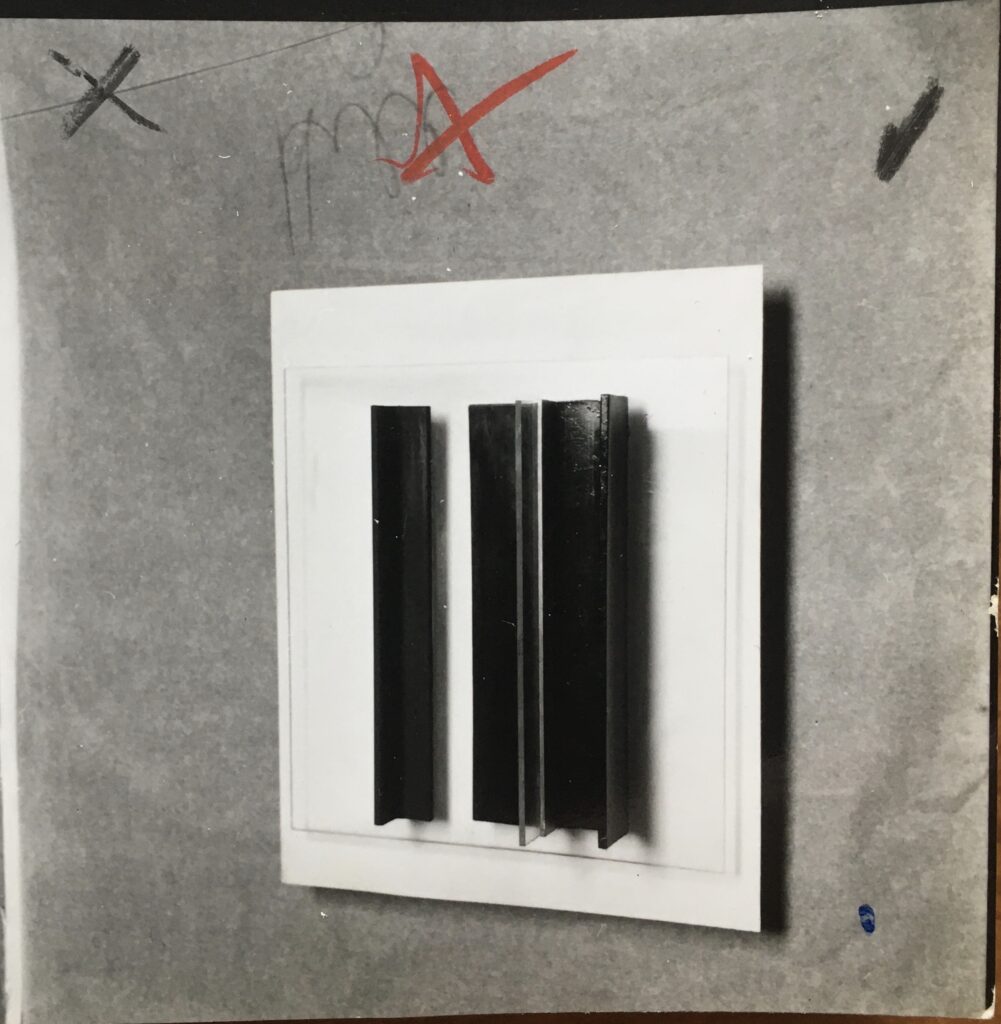

design by Raymond Hawkey, photograph by Adrian Flowers, October 1966

In his essay in London Dossier Flowers advises the aspiring photographer to first of all buy an umbrella, at James Smith & Son, 53 New Oxford Street. This landmark at the corner of New Oxford Street and Shaftesbury Avenue still sells—according to its tarnished and extravagant Edwardian window signage, dagger canes, swordsticks, tropical sunshades, Irish blackthorns and umbrellas. “Get a large one and on leaving take a picture of this changeless shop” wrote Flowers, adding that even the act of carrying an umbrella, for the superstitious, might prevent rain. Although Smith’s survives, all the independent specialist photography shops mentioned by Flowers are now gone; their place taken by chains such as Jessops and the recently-merged Wex and Calumet. Specialising in Flowers’ favourite camera, the Hasselblad, the Photo Centre in Piccadilly Arcade has long since given way to a shoe shop, while Dixons on Oxford Street is now home to a Carphone Warehouse.

At 93 Fleet Street, the venerable Wallace Heaton shop, notwithstanding its royal warrant, is now an outlet for mobile phones. Many of the early negatives in the Adrian Flowers Archive are preserved in distinctive green Wallace Heaton envelopes. The company, which also had a shop at 127 Bond Street and published the famous photographers “Blue Book”, was taken over in 1972 by Dixons.

Likewise, Pelling & Cross at 104 Baker Street, specialising in Voigtlander cameras, is gone, while Kafetz Cameras, down the road at 234 Baker Street, is now home to Vy’s Nails. Flowers identified the Kodak Instamatic and Voigtlander Bessy-K cameras as most suitable for beginners. For more serious photographers he recommended the Nikkormat, with 28, 50 and 105mm lenses, but for maximum versatility, he suggested the half-frame Olympus Pen D2 or Canon Dial. Agfa CT 18 film was good at capturing the grey London fogs, but Flowers warned that the colours red and green were inescapable, in a city full of buses, parks, guardsmen and pillar boxes. The budding photographer was invited to go to St. James’s Park at three in the afternoon, when the pelicans were fed with herring. Moving on from there, the top of Lambeth Palace would afford a panoramic view familiar to Canaletto. However if admittance to the palace proved difficult, Flowers suggested the landing stage by the river, where the Decca radar company had established its head office. Moving along, the photographer would head to the Beefeaters and ravens at the Tower of London—the latter best photographed from the top of the Port of London Authority, and from thence proceed to Tower Bridge. Flowers includes in his itinerary that ‘quarter mile of sordidness for the sinister-seeking’; the area of East London made infamous by Jack the Ripper, with Christchurch at its centre. “Ripper’s Corner in Mitre Square has only one wall remaining. This is where the body of Catherine Eddowes, his fourth victim, was found. I suppose it is like collecting pregnant silences on tape, but even so, if you are interested in Jack the Ripper and have read all about the rippings, the experience of photographing this bit of wall will have a strange effect on you. The wall is in the southerly corner and should be taken in the gloom of dusk with the aid of the gas lamps that are still there.” [Len Deighton’s London Dossier Penguin Books 1967, p. 150] After these dubious thrills, the reader was encouraged to explore Thrawl Street, and Flower and Dean Street (Flowery Dean). Commercial Road, Puma Court and Hanbury Street. Wilkes Street led to the Gilead Medical Mission, an organisation dedicated to bringing the Gospel to the Jews, not to be confused with present-day Gilead Science. Many Shoreditch slums had been cleared by then, the ‘Old Nichol’ being replaced by the splendid Arts and Crafts Boundary Estate. Flowers dwells on the area’s association with slaughter houses and butchers, singling out the Jolly Butchers pub (formerly the Turk and Slave) in Cabbage Court, 157 Brick Lane, as a good subject. The setting for an unofficial morning jewellery market in the 1960’s, the Jolly Butcher closed in 1987 and now houses a café, sandwiched between two bagel shops. “To round off the visit, not forgetting to visit some dark and sinister laneways, wend your way to the Cosy Café in Cheshire Street.” [p. 150] Famed for its egg, bacon and bubble, this establishment is also sadly no longer in business. The building survives, just about, in a boring modern streetscape utterly devoid of character. Beside the Cosy Café, an alley led to a footbridge over the railway lines.

Flowers recommended twilight as the best time of day for taking photographs in London, singling out the Victoria Embankment, and the promenade between Westminster and Lambeth bridges on the south side, as good for night shooting. “Trafalgar Square is worth taking at dusk. . . During the day Nelson can still look admirable without his column, apparently standing on a wooden box when viewed from Carlton House Terrace. At the end of this terrace is an unusually well-preserved example of bomb damage, contrasting strangely with the surroundings.” [p. 150] For explorations of Soho, Flowers recommended beginning in Compton Street, and that the photographer try to look like a tourist ‘to avoid being lynched’.

Not long after opening in 1959, at the corner of Dean Street and Romilly Street in Soho, the Trattoria Terrazza had become one of London’s most popular eating places for people from the world of theatre and advertising. Run by Franco Lagattolla and Mario Cassandro, the “Trat” had genuine Italian friendliness and style, and served good Italian food. Less formal than Le Caprice or the Ivy, more exciting than other Soho eateries such as L’Epicerie or Wheelers, nothwithstanding Francis Bacon and Lucien Freud occasionally holding court in the latter, it was a fun place to meet, attracting regulars such as David Puttnam, Raymond Hawkey, Len Deighton and Adrian and Angela Flowers. Deighton wrote passages of The Ipcress File at the Trat, including mention of its cuisine, and it was here he met Michael Caine, before the novel and film brought both fame. While Cassandro was outgoing and charming, not a little of Lagatolla’s more reserved style is captured in the persona of Harry Palmer created by Caine. Other diners included David Niven, Brian Duffy, Julie Christie, Terence Stamp, David Bailey and Jean Shrimpton. The interior was remodelled in the 1960’s by Enzo Apicella, who created a spare, white Modernist space, while retaining a rustic flavour, with tiled floor, rush-covered seats and rough-plastered walls—a style emulated by countless other trattoria that sprang up in Britain over the following years, and is still exemplified in better restaurants such as Scalini’s in Chelsea. Flowers’ night snapshot of the exterior shows the cheerful neon sun motif that reflected the Trat’s legendary charm and style. No 19 Romilly St is today occupied by Le Relais de Venise, a dull steak and chips establishment with an exterior of gothic lettering and scumbled wood that caters mainly to tourists.

Flowers also suggested hiring a taxi to tour the streets slowly ‘you can get many fascinating shots this way’. Leicester Square was best photographed from Cranbourn Street, while Lower Regent Street provided the best view of Piccadilly Circus.

Even with fast film, the photographer would need a tripod to capture flashing neon lights at night. Battersea Park, with its Henry Moore sculpture, was on the itinerary, with the nearby power station chimneys still belching out smoke. The 29th of May, Oak Apple Day, saw pensioners of the Royal Hospital Chelsea on parade, while the Chelsea Flower Show, also held in May, was a treat, particularly at 4pm on the last day, when plants were sold off cheaply. ‘If you could get a hundred viewpoints at once, you’d have the film of the year.’ observed Flowers drily. Leather Market Street south of Guy’s Hospital on Friday mornings, and the Caledonian Market on Bermondsey Street, were charming to photograph, as were Portobello Road and Petticoat Lane. Flowers was less comfortable with Victorian architecture – ‘If wild monstrosities are your passion start with the Albert Memorial’. Berkeley Square, King’s Road, Chelsea – ‘If you want to see and not be seen, a good tip is to grab a window table in the pub called the Chelsea Potter about midday.’ Horse riding at Rotten Row, Hyde Park, every morning, and the dray horses still used by Whitbread Brewery in Chiswell Street and Watney’s Mortlake brewery. St. Paul’s Cathedral was a favourite. The viewing terrace of the Shell Building could be visited for two and sixpence, but closed at four in the afternoon, which was disappointing for photographers hoping to shoot at twilight. The GPO tower was also disappointing, due to haze, but the Monument provided a good view of Tower Bridge. Flowers recommended the Tudor houses at Holborn, Chancery Lane, and Lincoln Inn Old Buildings, where barristers in their regalia could be seen at lunchtime. Other sights included the Old Curiosity Shop, and men wearing bowler hats, still a common sight at London Bridge in the morning, and at Cornhill and Lombard Street.

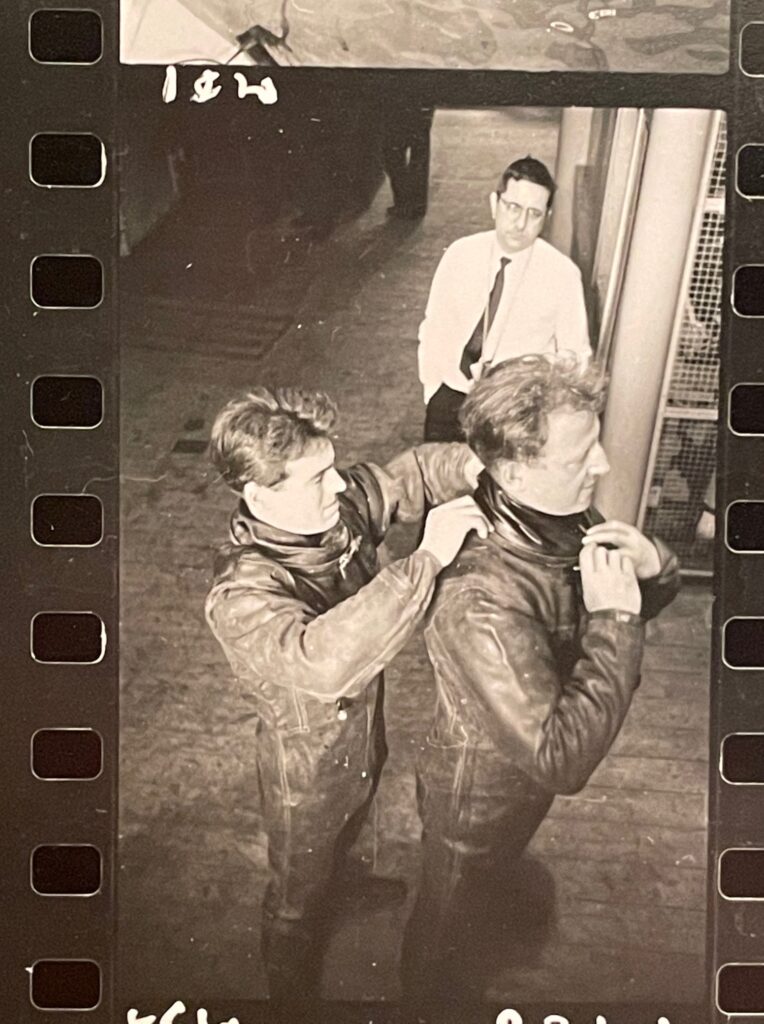

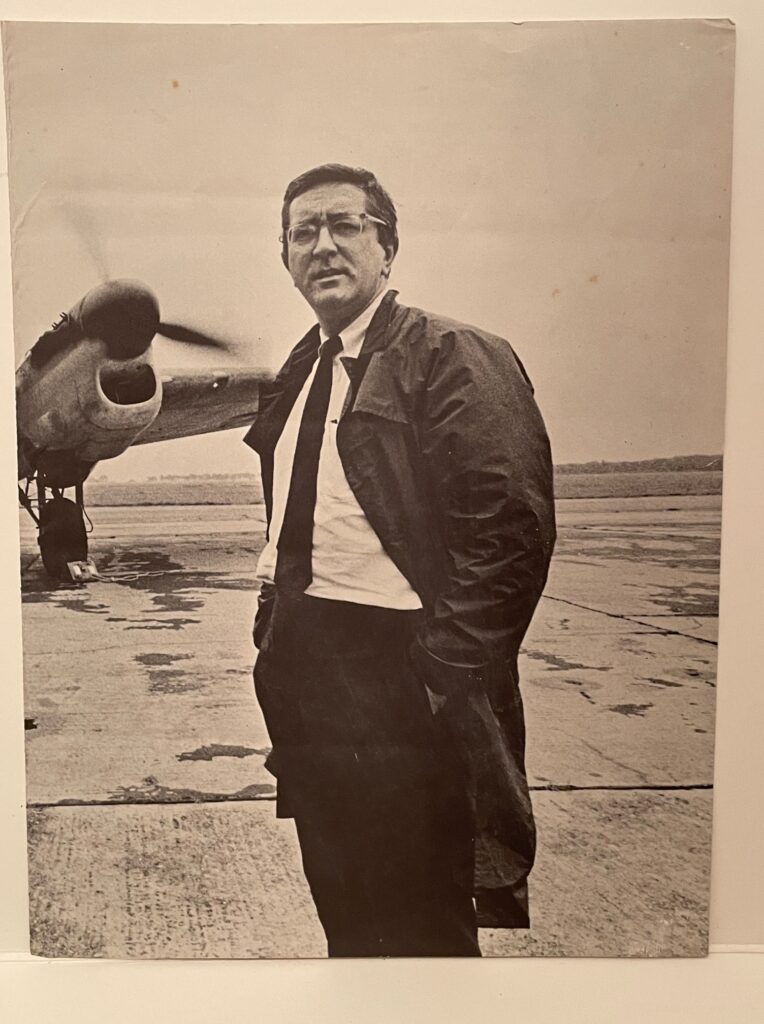

Adrian Flowers 1966

Photographers were advised to take the 214 bus from Tottenham Court Road to Highgate West Hill, and to go through Hampstead Heath, on to Kenwood House, and then to the Spaniard pub. They would then to take the 210 bus to Highgate Village, and from there walk down Swains Lane to the cemetery, for Flowers a place he held sacred as the burial place of the pioneer of photography William Friese-Greene. Regent’s Park Zoo and Tilbury Docks, the bridge on the River Thames, all received honourable mention, while Flowers recommended photographing the London Policeman ‘still proudly not carrying a gun’. The Roman wall at Cooper’s Row, off Trinity Square, the Natural History Museum, the Science Museum and London’s fire stations were all on the list. Flowers highlighted details such as cast iron railings, although many of these had been melted down during WWII. His final suggestion was to go to a theatre near Covent Garden, eat and drink into the early hours at one of the specially licenced pubs “Then, at 4 or 5 in the morning use stamina to judge, with an unjaundiced eye, the picture-making possibilities of the famous flower and fruit markets.” [p. 157]

Text: Peter Murray

Editor: Francesca Flowers

All images subject to copyright.

Adrian Flowers Archive ©