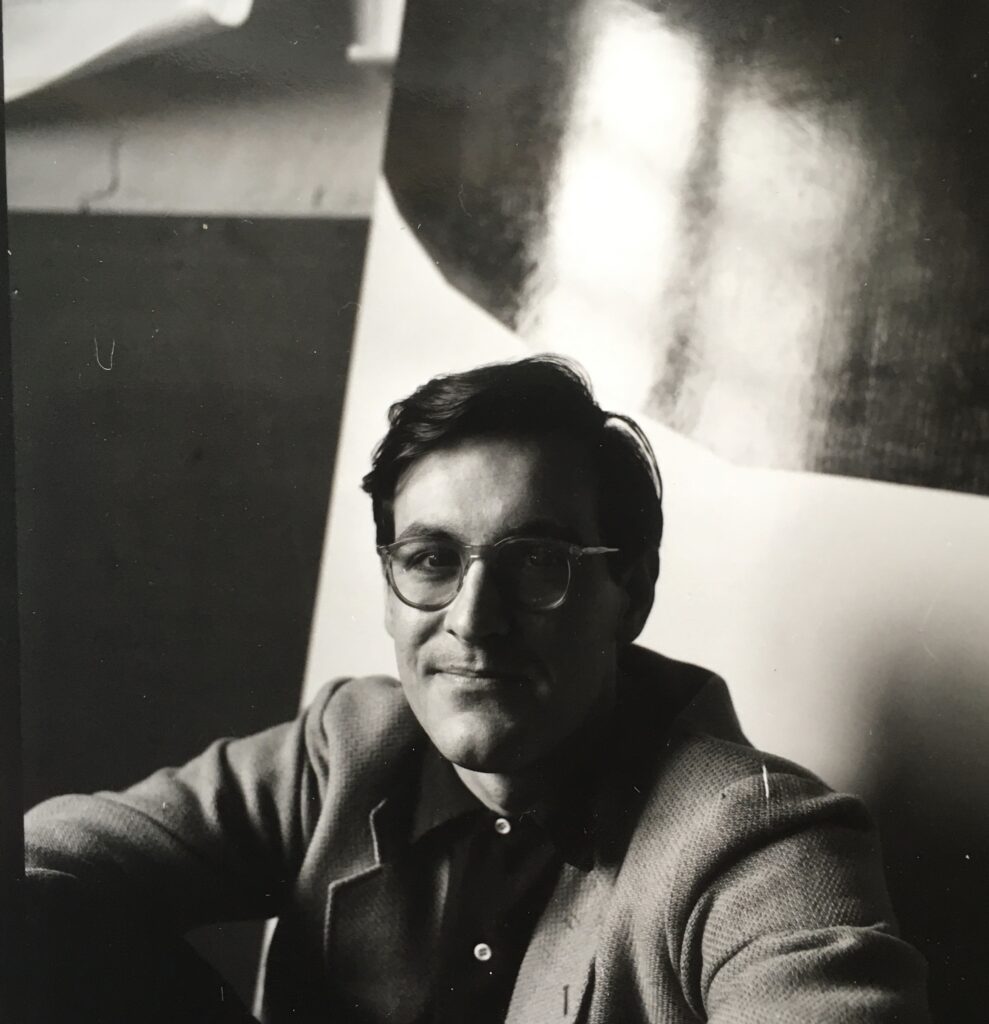

Constructionist artist

April 1930 – October 2020

Photograph: Adrian Flowers

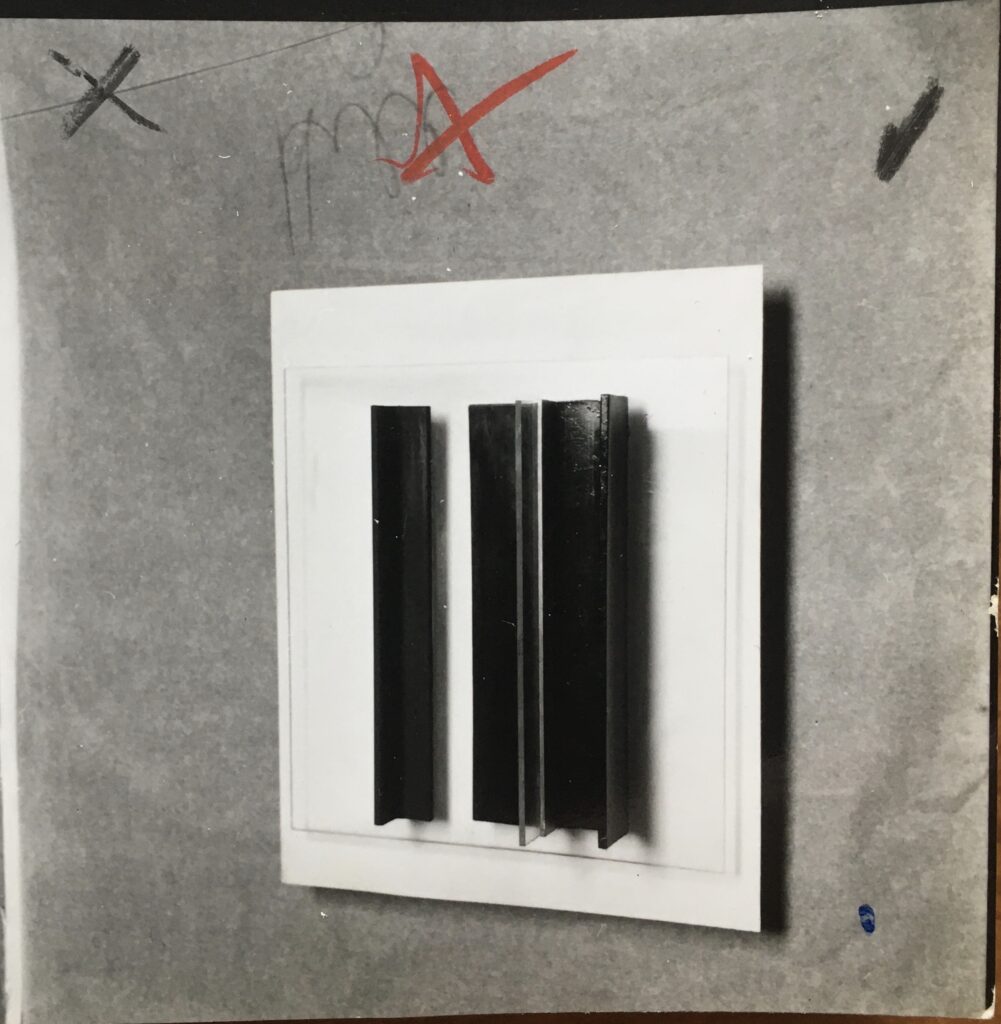

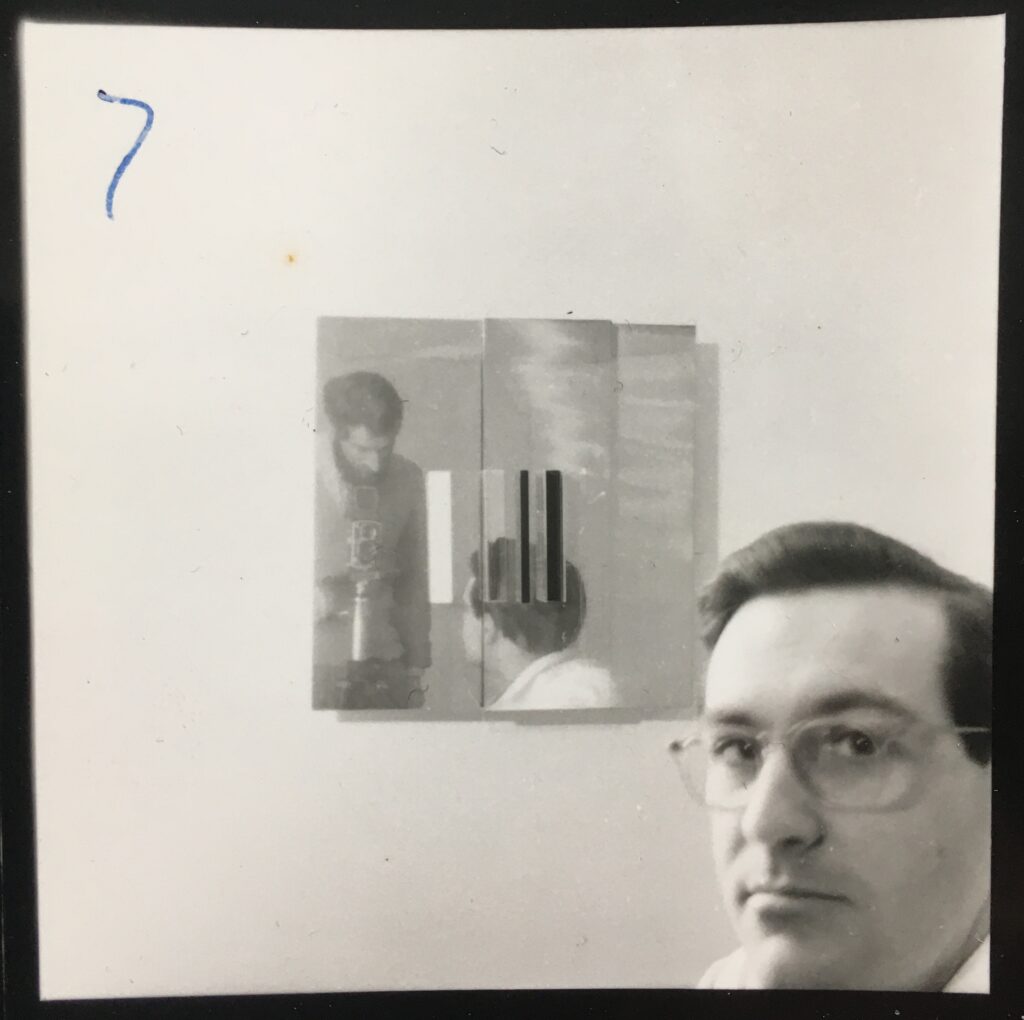

Adrian Flowers: job no. 2025 June 1956 Anthony Hill (1930-2020), artist

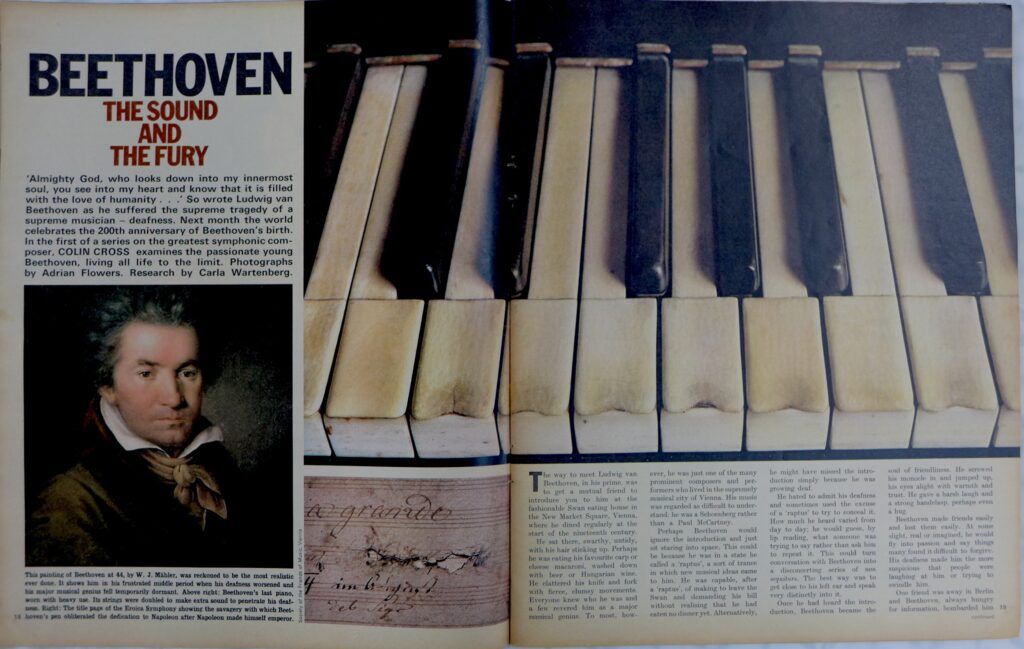

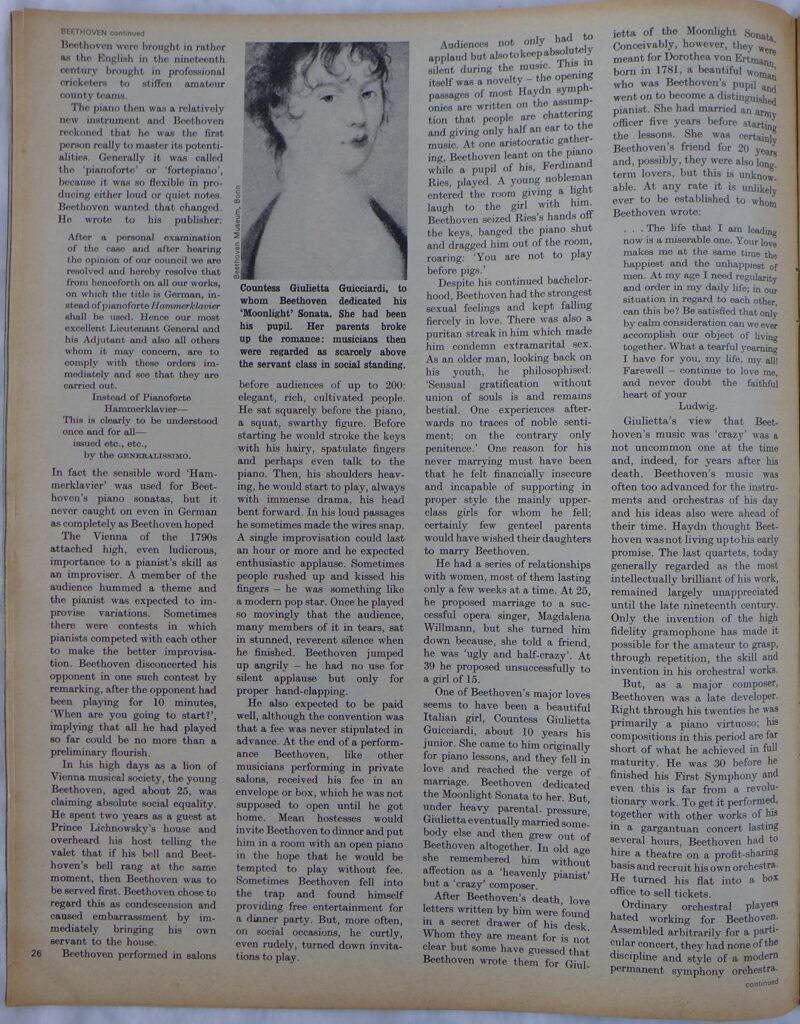

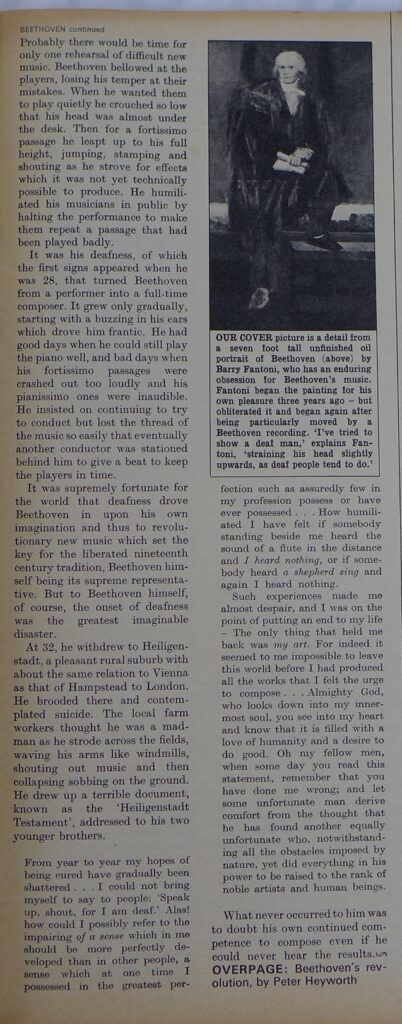

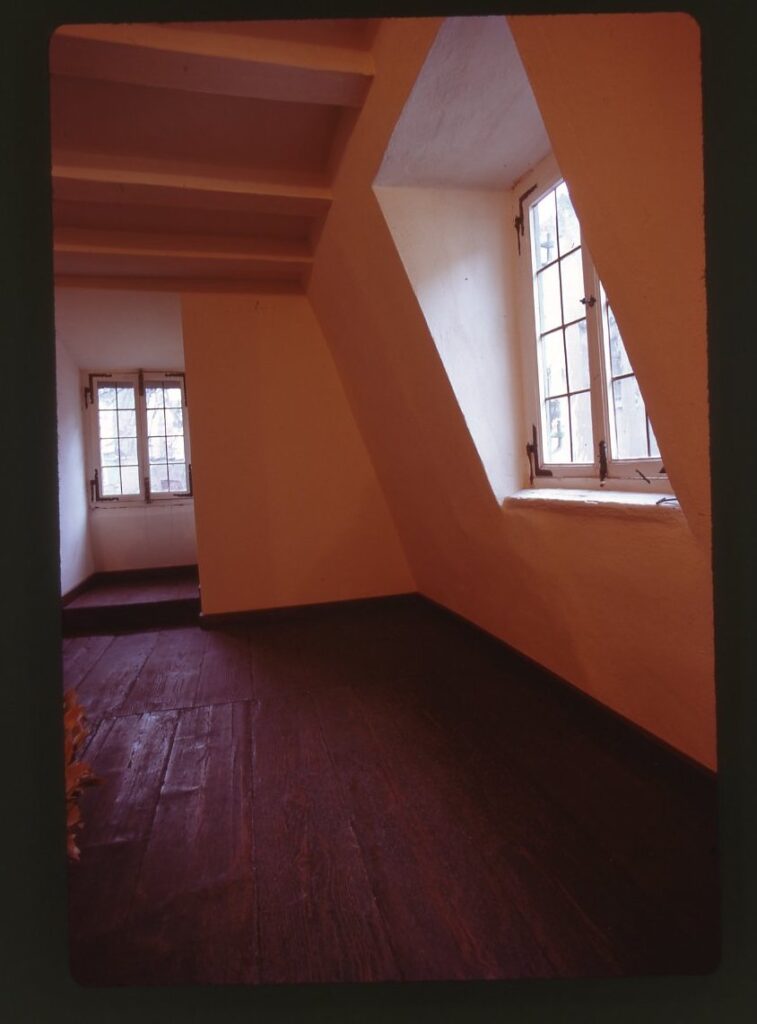

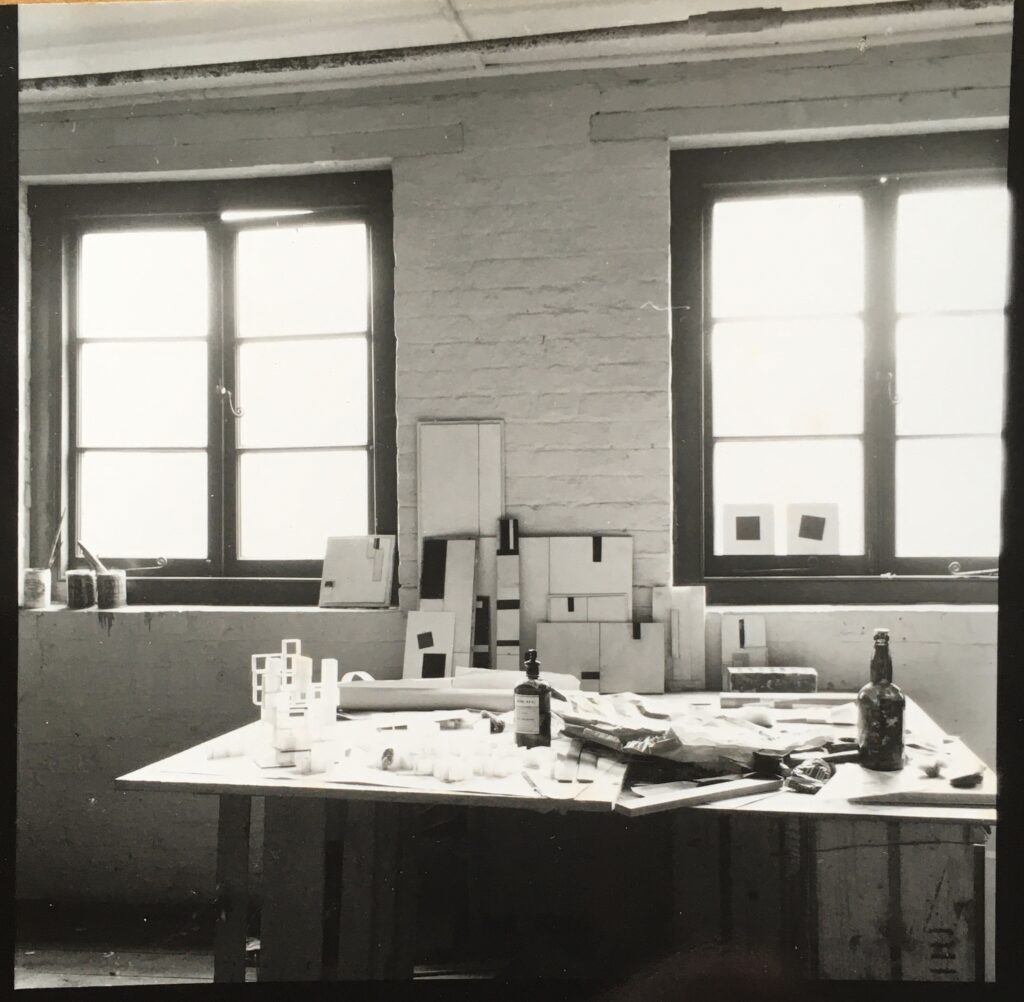

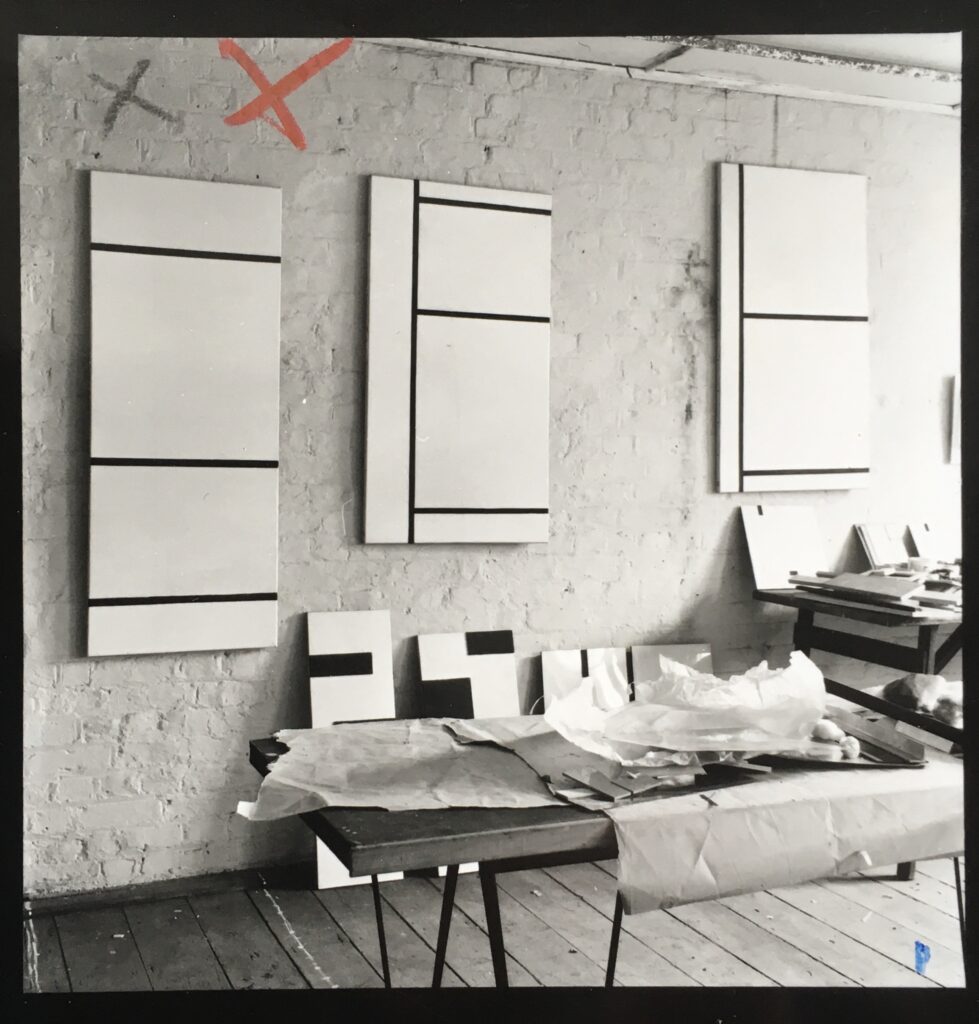

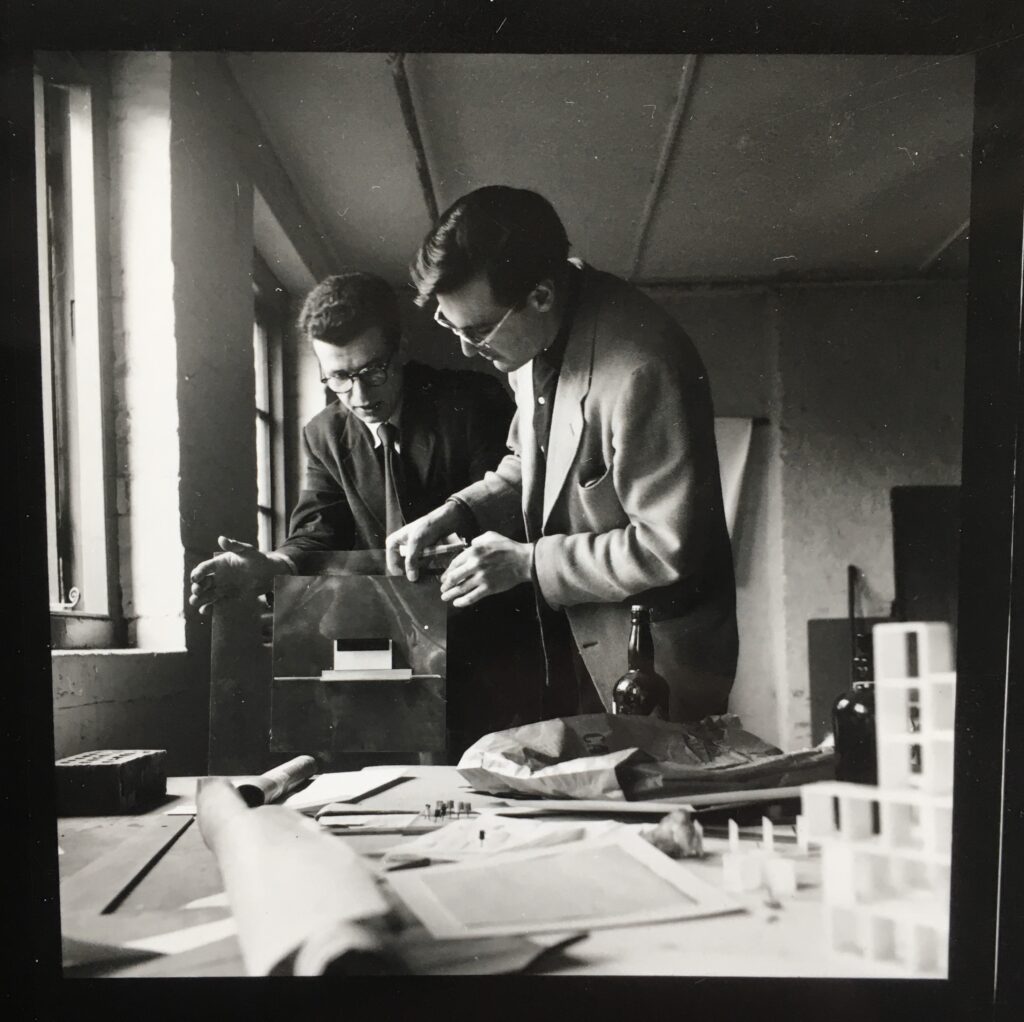

Famed for its spielers, houses of ill-repute and establishments such as the Coach and Horses and l’Escargot, Greek Street is still today the centre of London’s bohemian quarter. Extending from Soho Square to Shaftesbury Avenue, over the centuries the street had been home to many artists, including Canaletto, Peter Turnerelli, Thomas Lawrence, Richard Westall and William Etty. In 1956, the artist Anthony Hill had a studio on Greek Street, where he was completing a series of abstract ‘concrete’ paintings and wall-mounted reliefs, in preparation for the forthcoming This is Tomorrow exhibition at the Whitechapel Art Gallery. (The term ‘concrete’ describing abstract works that refer to themselves rather than to external reality). In June of that year Adrian Flowers visited Hill’s studio, to photograph the artist and his work. The shots taken that day show that Hill was moving away from conventional oil paintings, preferring instead to make three-dimensional relief paintings/sculptures, using modern materials such as Perspex and aluminium. One of the works that appears in a Flowers’ photograph, Painting 55-56 (Tate collection) was among the last oil paintings made by the artist. Hill described this work as a study in texture and reductionism, with horizontal lines suggesting the canvas was bound by bands. However the photographs taken in 1956 by Flowers inadvertently—or perhaps deliberately—provide a gentle critique of the concept of ‘concrete’ paintings, in that one shot on the contact sheet shows two square windows of the Greek Street studio, with simple astragals, while the next is of Hill’s geometric abstract paintings with their slender cross-bars motifs. Not only did Flowers photograph the paintings, he also took a series of shots of Hill and his collaborator, sculptor John Ernest, standing over a set of free-standing modular cube-like structures. Hill and Ernest were both keen mathematicians, and worked together on ‘crossing number’ in graph theory, an area of research that directly informed Hill’s art.

Concrete paintings by Anthony Hill in his studio, 1956.

Photograph: Adrian Flowers

Born in 1930 in London, from an early age Hill was fascinated, and indeed obsessed, by mathematics. At the age of seventeen he enrolled as a student at St. Martin’s School of Art, moving on two years later to the Central School. Initially working in a Dada and Surrealist style, his interest in mathematics led him to become interested in geometric abstraction, which he felt represented a more rational aesthetic. Visiting Paris in early 1950, he met Sonia Delaunay, George Vantongerloo (a founder member of De Stijl) and Francis Picabia. Another artist who influenced him was Frantisek Kupka, of the Orphic Cubism movement. Hill was particularly inspired by Piet Mondrian’s work and the following year joined the “Constructionist Group”, a late offshoot of the Constructivist movement associated with revolutionary Russia. Other members included Kenneth and Mary Martin, Adrian Heath, Roger Hilton, William Scott, Victor Pasmore and Robert Adams—the latter two were at the Central School at the same time as Hill. Publishing a manifesto-like Broadsheet that same year, the group showed their work both at Gimpel Fils and the AIA Gallery, in exhibitions entitled British Abstract Arts and Abstract Paintings Sculptures Mobiles respectively. The Constructionists were not working in a vacuum, but were in touch with artists on the Continent, including Marcel Duchamp, the Swiss abstractionist Max Bill, and the American abstract painter Charles Biederman. They avidly read Biederman’s 1948 treatise, Art as the Evolution of Visual Knowledge.

Photograph: Adrian Flowers

The Constructionists epitomised the search for a Modernism that would be viable within the complex aesthetics of post-war Britain. Although he had been making geometrically-based collages for some time, in 1952 Hill made his first abstract relief. By 1953, he had abandoned colour, and was making stark black and white paintings, in which geometry and free-form drawing were held in tension. A large painting (now lost) Catenary Rhythms was included in the exhibition Artist versus Machine held at the Building Centre, London, in 1954. That same year, along with Stephen Gilbert and others, Hill featured in Lawrence Alloway’s Nine Abstract Artists, a book which sought to distinguish between ‘genuine’ abstract art, and the more or less random styles adopted by those who had rejected figurative art, but who Alloway felt followed no coherent aesthetic. Alloway’s preference for ‘structural’ artists such as Hill, William Scott, Terry Frost and Kenneth and Mary Martin, was based on a conscious opposition to the expressive abstraction epitomised by Peter Lanyon and other St. Ives artists. The group showed at the Redfern Gallery in 1955, with a catalogue written by Hill and the following year were given prominence in the Whitechapel exhibition This is Tomorrow. Adrian Flowers was a steady presence at the centre of this ferment of creativity, photographing the artists in their studios as they prepared their work for exhibition.

Photograph: Adrian Flowers

After the Whitechapel exhibition, Hill gave up painting entirely, concentrating instead on three-dimensional work. In 1958 his reliefs were shown at the ICA, by which time he was incorporating sheet copper, brass, zinc and stainless steel in these wall-mounted works. The following year Hill and Gillian Wise, another graduate of the Central School of Art, became partners, and in 1962, Hill organised the exhibition Construction: England: 1950-60 at the Drian Gallery, a space founded by the Lithuanian Halima Nalecz, to represent artists excluded from West End Galleries. This was to be the last group exhibition of the Constructionists, and apart from the support of a small band of loyal curators and collectors, they faded from view. Hill and Wise went on to collaborate on works, including Metal Relief with Horizontal Elements (1962) now in the National Galleries of Scotland. In 1963 the couple showed in the exhibition Reliefs/Structures at the ICA.

Based on a high-minded aspiration towards an art that was self-referential and bore no relationship to the world of visible reality, Hill’s aesthetic was intellectual and personal. His often dogmatic assertion of the primacy of this approach led him to write theoretical essays, to explain his approach to making art. However, even within the rarefied world of mathematics, assertions of neutrality were not possible, and Hill’s art and writings can be read today as polemical, personal and even combative assertions regarding society, aesthetics, and the politics of his time. In 1968 Faber and Faber published Data: Directions in Art, Theory, and Aesthetics, a compilation of essays edited by Hill that consciously echoed the 1938 publication Circle, which had featured Naum Gabo, Ben Nicholson and others. Hill’s introductory essay, reflecting his own rigorous approach to making art, was entitled “Programme, Paradigm and Structure”. The following year, led by Jeffrey Steele, a number of UK artists working in this mode formed the “Systems Group”. Less committed to Marxist ideologies, Kenneth and Mary Martin, along with Hill, preferred not to become involved. However Wise, who had been researching Russian Constructivism in the Soviet Union, did join, and eventually this led to her breaking with Hill, who went on to pursue his own career. He subsequently married the Japanese ceramic artist Yuriko Kaetsu (1953-2013). In 1983 he had a retrospective exhibition at the Hayward Gallery and by the early 1970’s was making free-standing geometric constructions. In 1973-4 he adopted the name Achill Redo, under which moniker he exhibited at the Mayor Gallery and Angela Flowers Gallery, and wrote texts that pay homage to the Dadaists and Surrealists. In 1994 his Duchamp anthology Duchamp: Passim was published by Gordon and Breach. In 2012, he was included in the exhibition Concrete Parallels in Sao Paulo, Brazil. By this time, Hill was suffering from bouts of depression that sometimes made it impossible for him to welcome visitors to his studio, and was retreating into an intellectual and personal universe not unlike that of Humphrey Earwicker in James Joyce’s Finnegan’s Wake.

“I asked LSC for a kick-start idea for do it. He gave me his take, but insisted I don’t credit him or refer to him by name. But I have done it. Lafcadio Svensen Carner, he said the short auteur’s cut was not to do it, to do nothing, i.e., it is not a thing you can overtly do. (How do they do it, these megamind pscientists?) They will never finally, really succeed in doing it when it = the grand theory about every it/thing. Best to switch to art, especially abstract art or pure absolutart—that’s where to aim (or aim to miss, as several stratagists convey). Re: doing it right, LSC said, “I could only come up with, you can either do it right or wrong, there is no tertium whatshit. (i.e. excluturd middleterm), there is the theologic of it. That and O’Kamm’s shaver, to the restcu.” (Achill Redo 2012)

Although characterised as an artist who championed rational intellect over emotional feeling, and methodical planning over spontaneous expression, Anthony Hill’s work reveals not only a love of mathematics, but also an appreciation of the intuitive nature of art making. His work was informed by the development of computer language, with its emphasis on logic and patterns of connectivity, and he was equally immersed in the ebb and flow of 20th century art movements, such as De Stijl and the Russian Constructivists, but ultimately there is a personal introspective quality in his art that reveals the extent to which he was on an increasingly solitary quest, exploring philosophical questions on the nature of human consciousness and apprehension of the world.

Anthony Hill died in October 2020

Text by Peter Murray

Editor: Francesca Flowers

All images subject to copyright

Adrian Flowers Archive ©