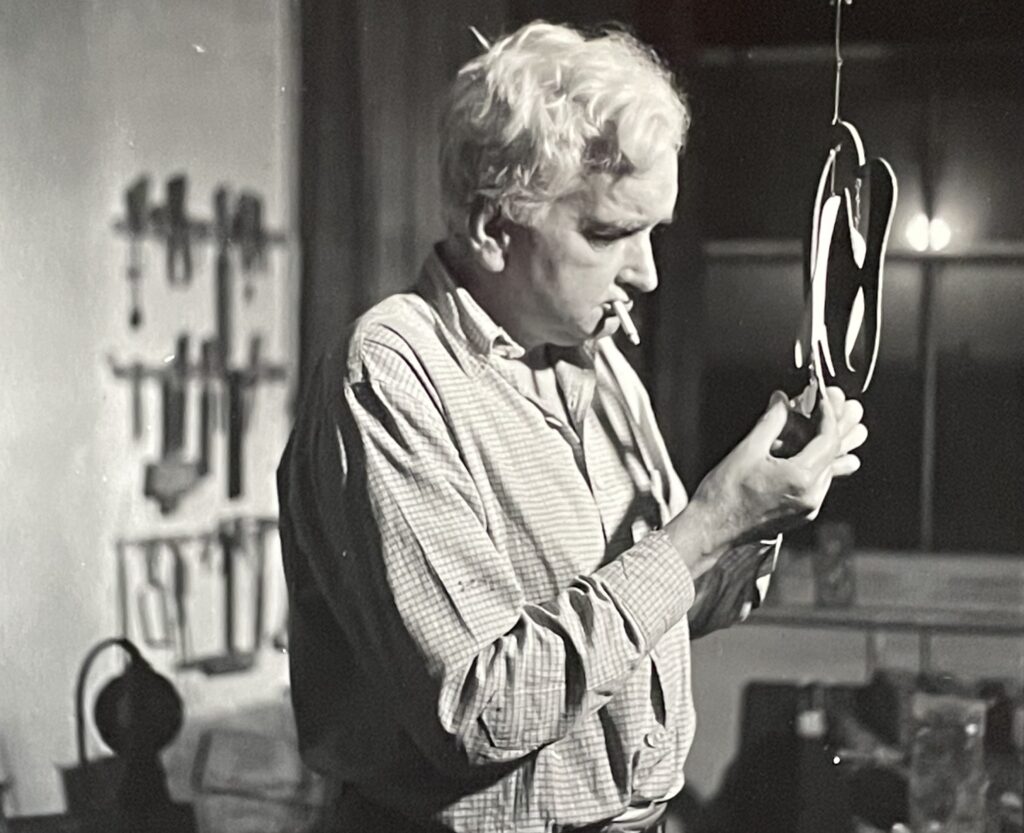

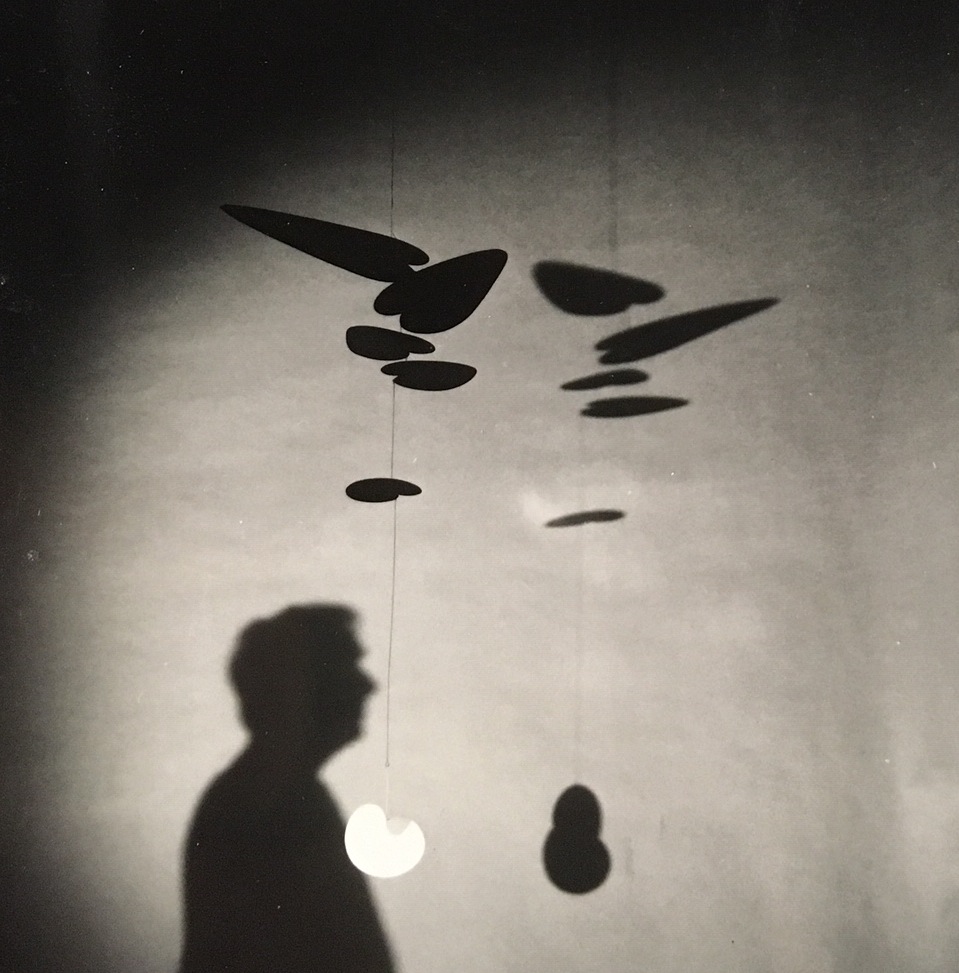

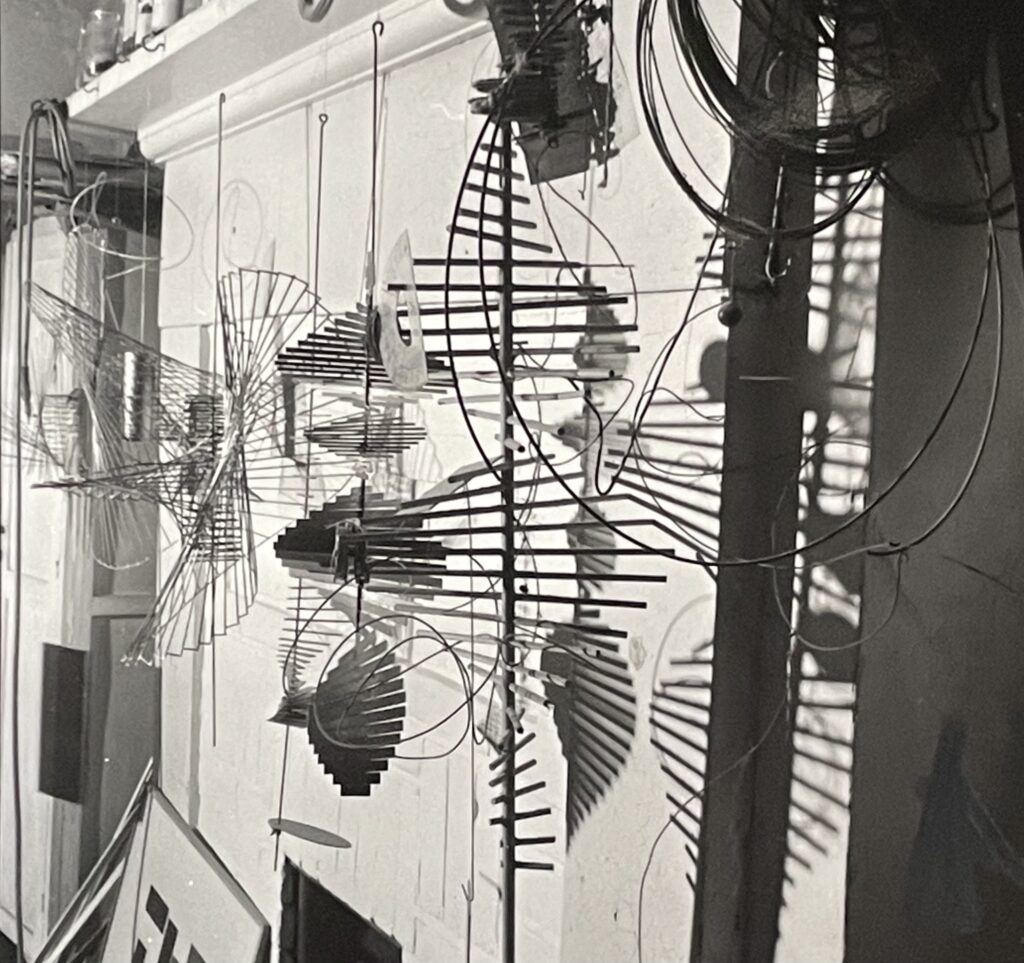

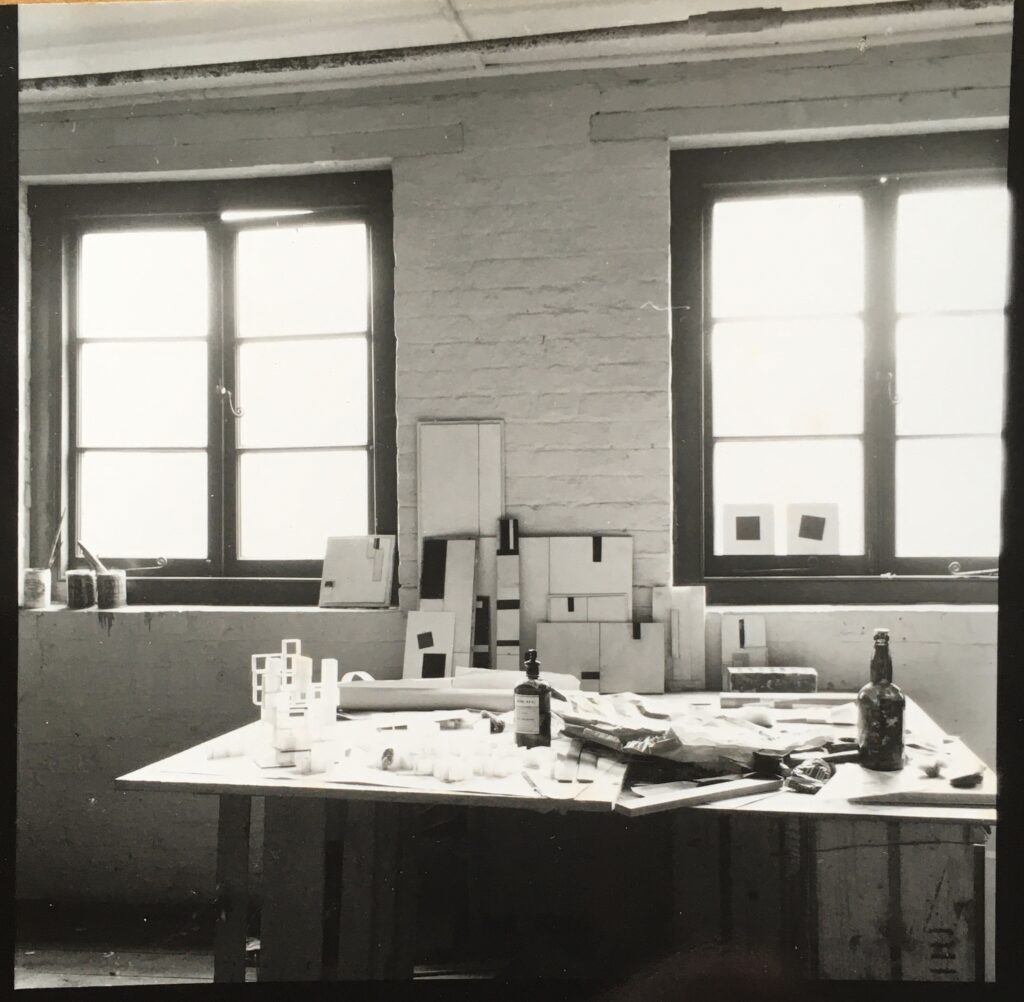

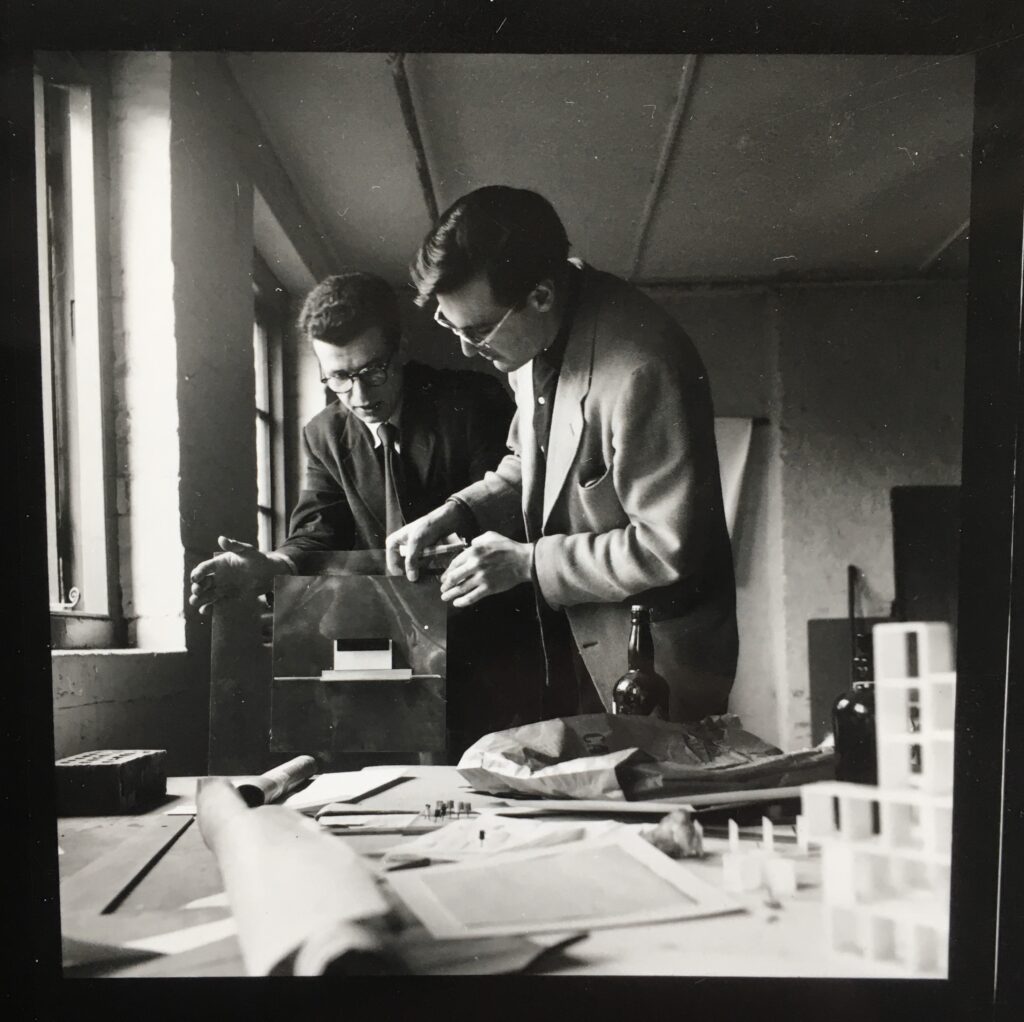

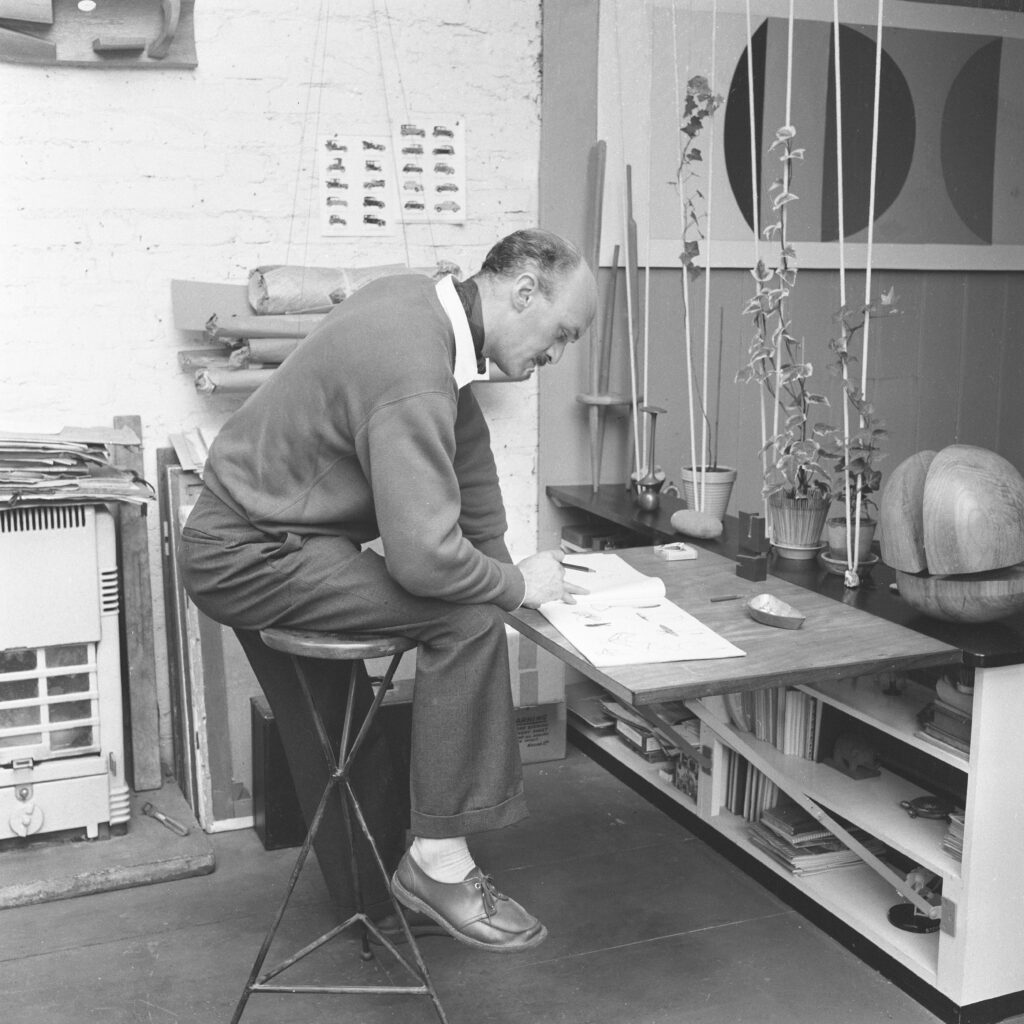

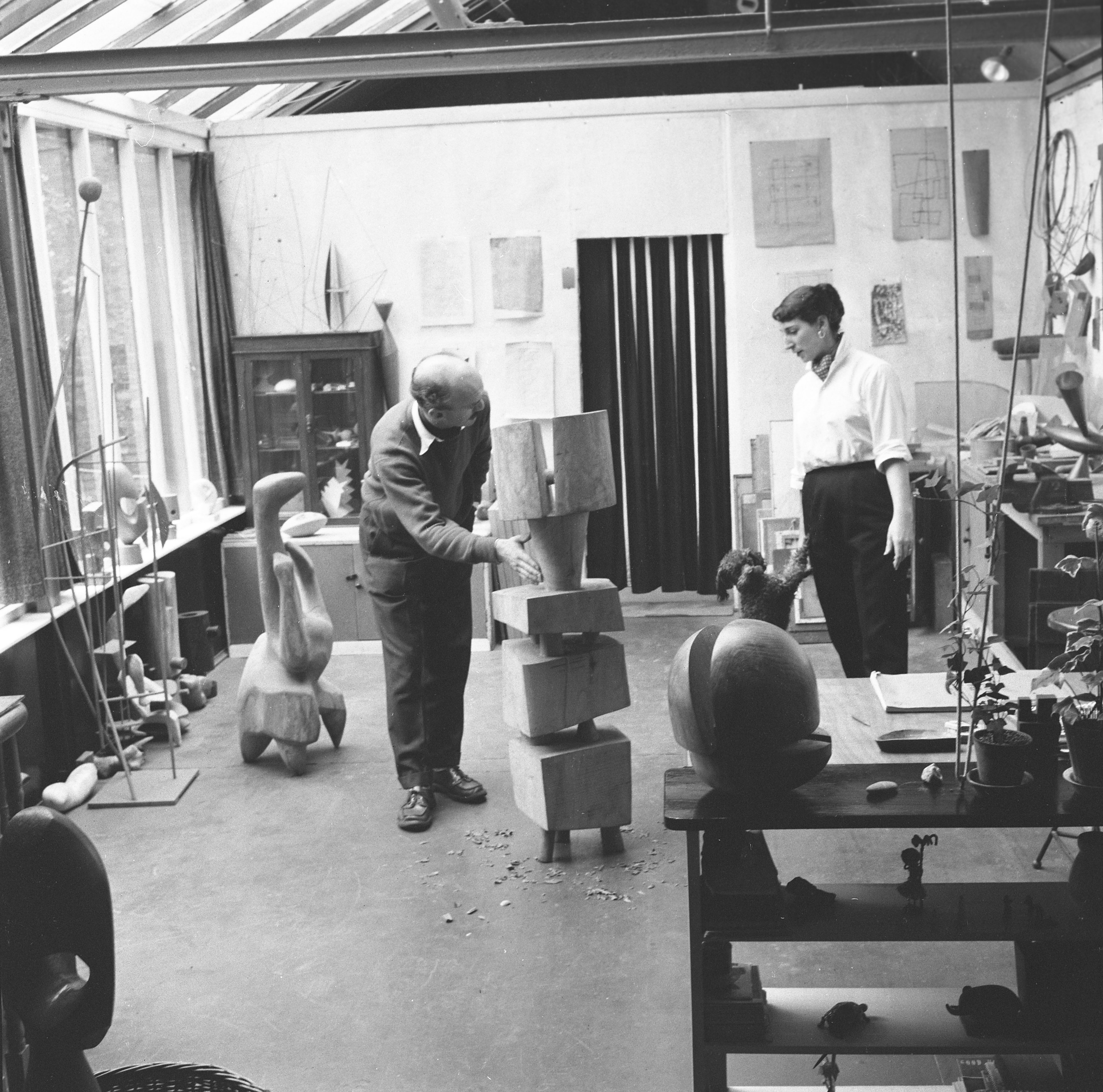

During the 1950’s and 60’s Adrian Flowers photographed the painter and sculptor Robert Adams on several occasions. One photo, taken around 1955 [AF 1750], shows Adams in his studio in London, sitting casually on a high stool made of welded metal, poring over a sketchbook on a drawing table. The form and construction of the stool suggests it was made by the artist. On a shelf are several of Adams’ sculptures. One, a small bronze work, part of the Growing Form series, dates from around 1953. Another relates to the ‘Penwith Forms’ series, and dates from 1955. Adams has dressed elegantly for the occasion of Flowers’ visit, and is wearing a white shirt and cravat. Behind the artist are rolls of drawings, cleverly suspended in loops of string. The drawing table is a fold-out affair, part of a room divider that also contains bookshelves. A large abstract painting can be glimpsed in the background. Another photograph taken on that same visit shows Adams working on a tall wooden sculpture. The sculpture stands on a workbench in the same studio, with its white-painted brick walls and overhead girders. On the walls are T-squares, a brace, saws and loops of wire. A third photograph shows Adams, his wife Patricia and their dog Tishy, surrounded by sculptures, including a welded metal piece from c. 1950, one of an abstract series inspired by drawings of dancers.

Photograph by Adrian Flowers

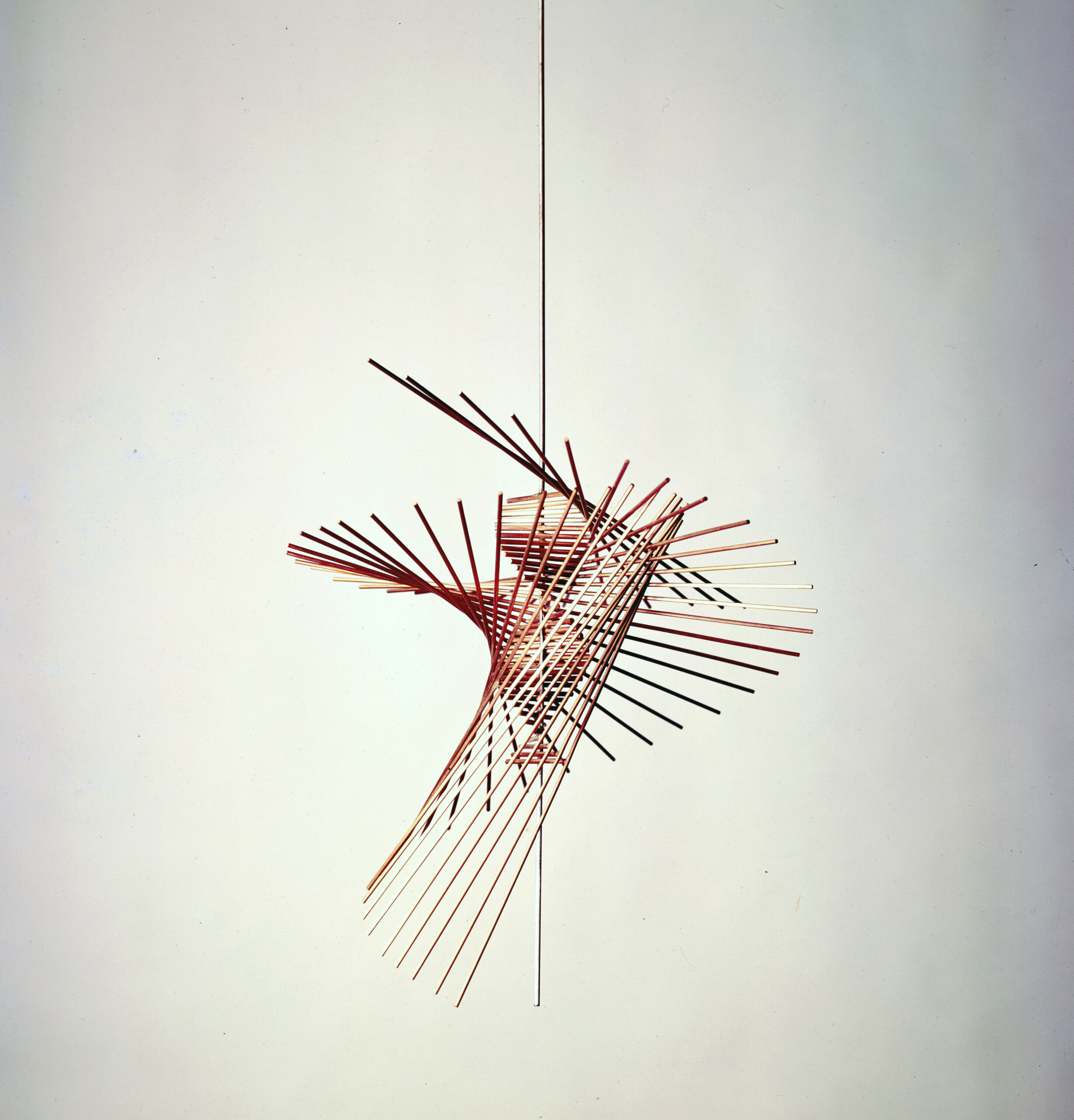

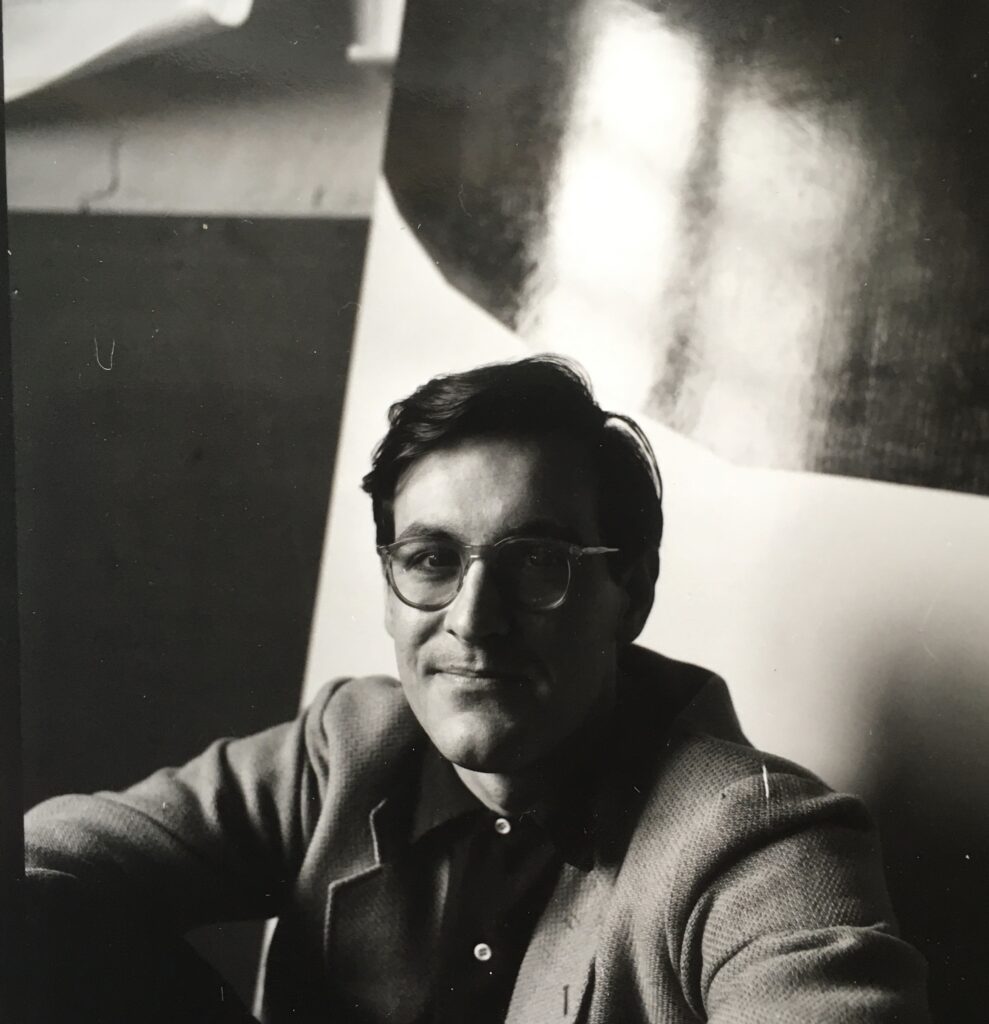

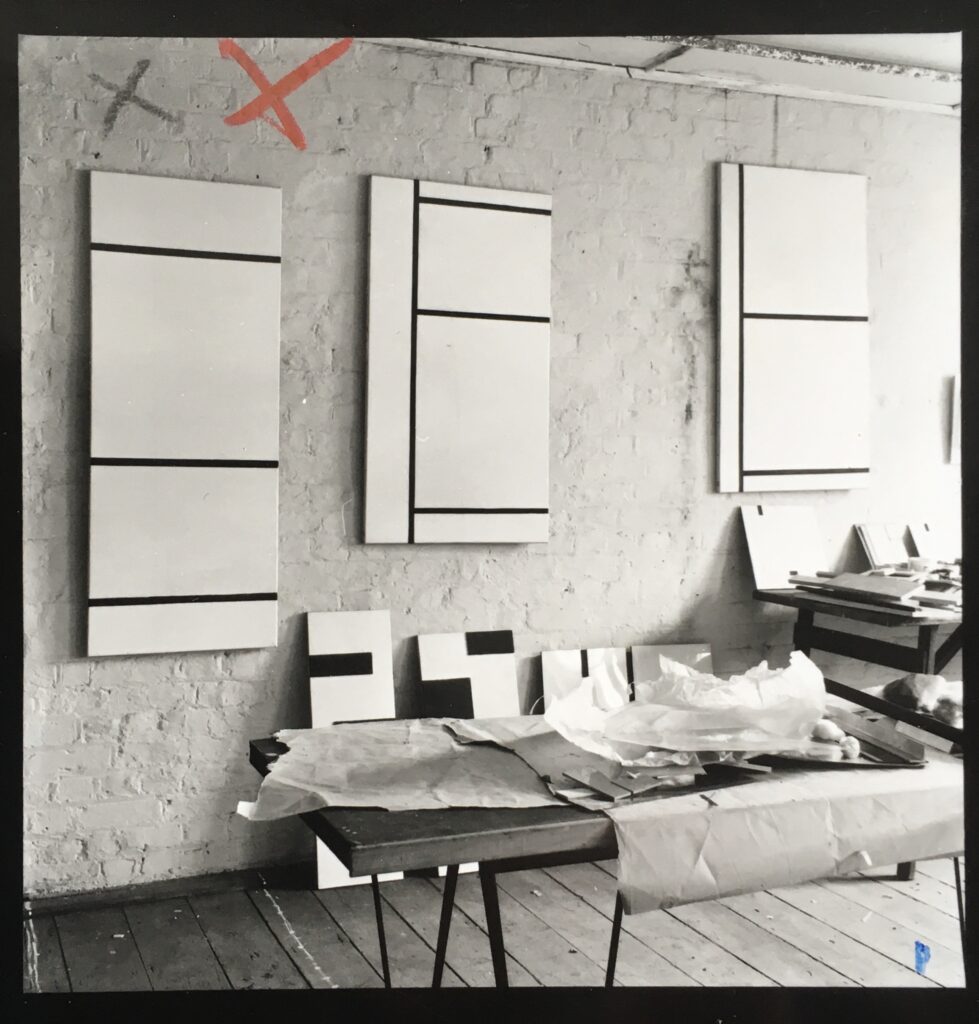

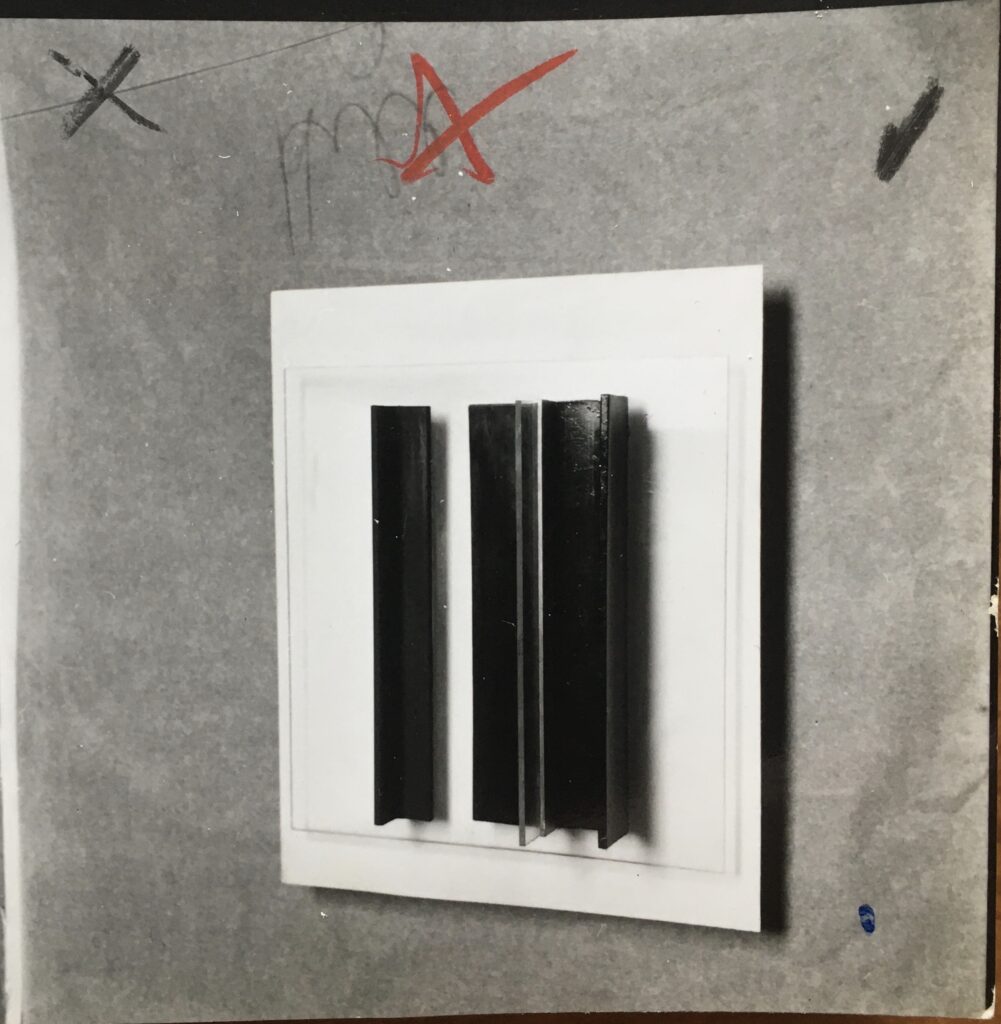

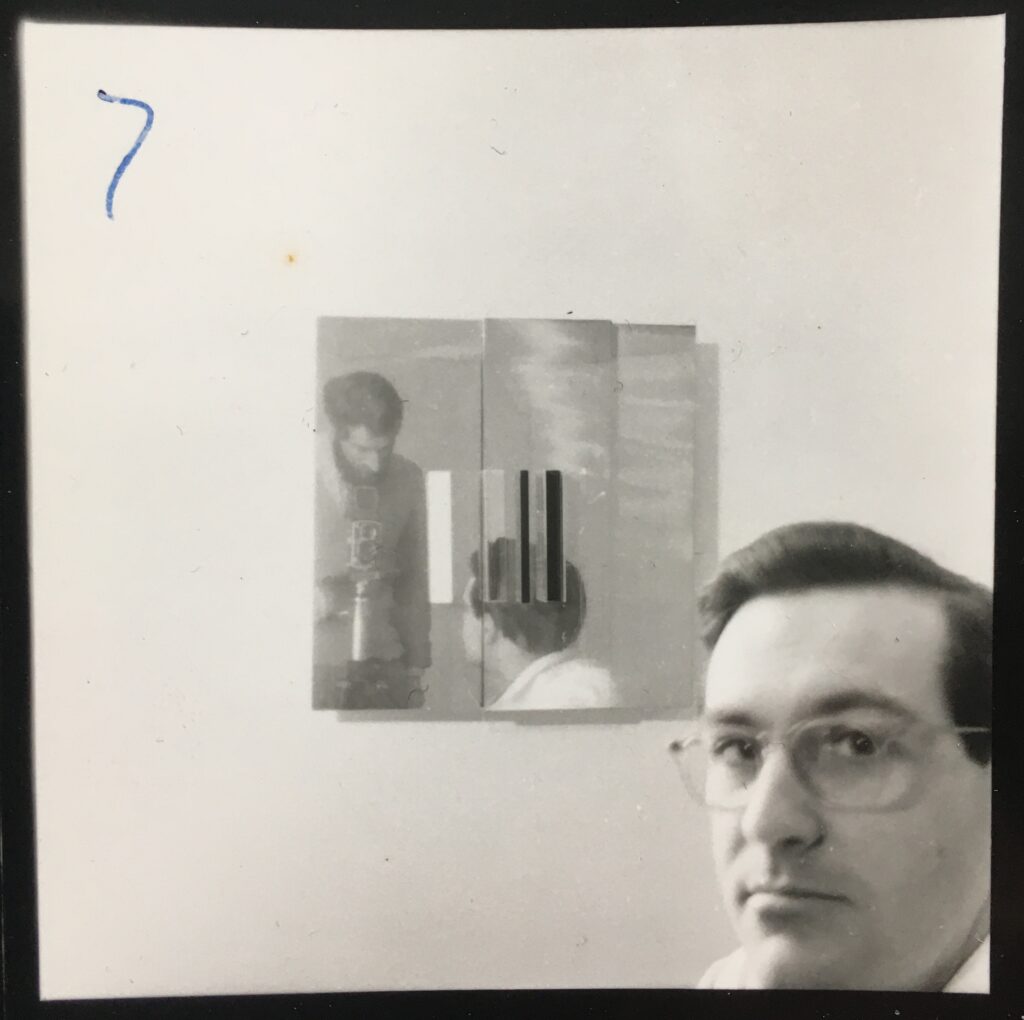

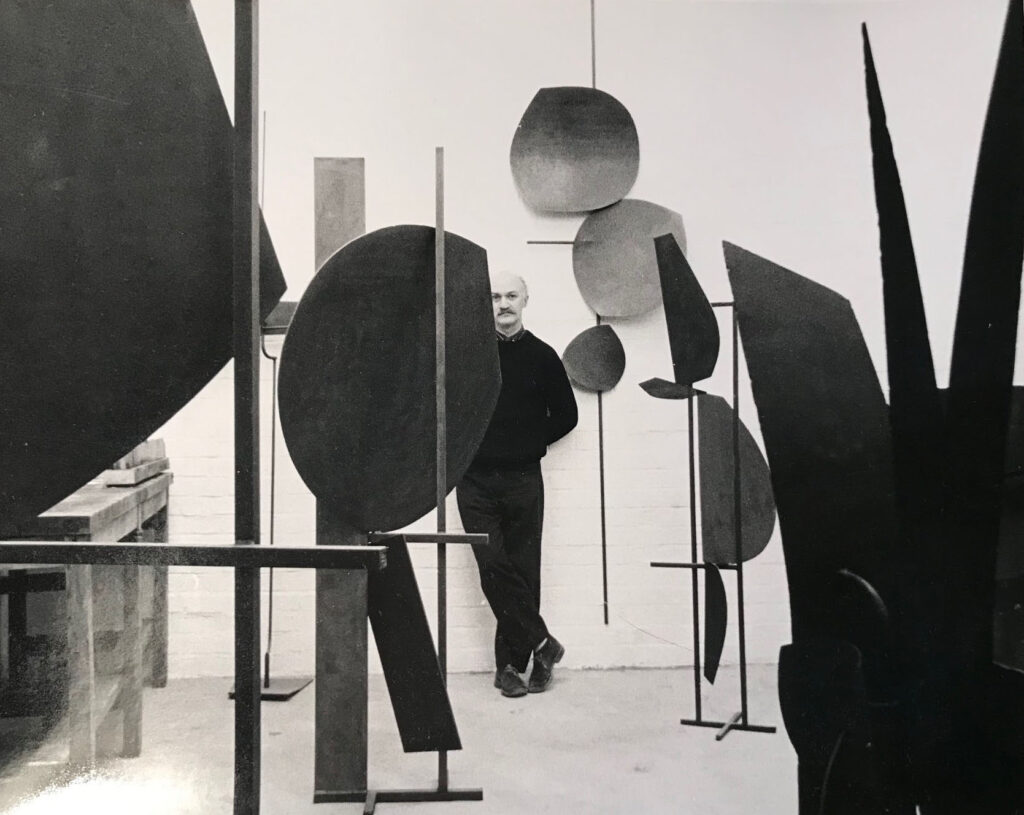

Several years later, around 1960 [AF 3376], Flowers photographed Adams in a park, with houses in the background [perhaps Hampstead Heath?], standing beside a large sculpture, made of straight lengths of metal rod welded together. This work is likely Triangulated structure No. 1, its form evoking the facets of a crystalline rock formation. Another set of photographs [AF 4217, 3376] taken around 1961, show Adams standing in his studio, surrounded by tall welded-metal sculptures. By this date, the artist’s work has evolved, and his now making tall free-standing and wall-mounted abstract pieces, in which circular plate-like forms are counterpoised with slender vertical and horizontal rods and bars. Adams also appears more confident in this set of photographs, smiling, relaxed, leaning against the wall. Another set of negatives [AF 2576] are of Adams’ carved wood sculptures set on plinths, and wall-mounted reliefs, displayed within a classical house setting. The sculptures on plinths are paired forms, evoking the streamlined wings and fuselages of aeroplanes.

Photograph by Adrian Flowers

Adams had a good grounding in the technical aspects of sculpture. Having left school in Northampton aged fourteen, he worked for a local firm that manufactured agricultural machinery. From 1937 to 1946 he attended life drawing and painting classes at Northampton School of Art, and during WWII was a fire warden in Civil Defence. He first showed his work in a series of exhibitions held at the Cooling Gallery in London, along with other artist members of Civil Defence. In the post-war years he turned firstly to abstract painting, then sculpture, working mainly in wood, slate, plaster and stone. Although he remained a resolutely abstract artist, in Adams’ work there is always an underlying regard for the world of nature, and for plant and human forms. In 1949 he began to work in metal and for a decade after, in addition to making his own work, taught at the Central School of Art in London. He was influenced by, and became part of, the London Group of constructionist artists that included Adrian Heath, Anthony Hill, Victor Pasmore and Kenneth and Mary Martin. In 1947 Adams was included in the inaugural exhibition of Living Art, held in Dublin, as well as having the first of a series of exhibitions with Gimpel Fils in London. Shortly afterwards he travelled to Paris where he encountered the work of Brancusi and Julio Gonzalez. In 1949 he showed at Galerie Jeanne Bucher in Paris, the Redfern Gallery in London, and, the following year, at the Passedoit Gallery in New York. In 1951 he was invited to exhibit at the Sao Paulo Biennial and the following year was included with the group of young British sculptors in the British pavilion at the Venice Biennale whose work, using innovative techniques and breaking with traditional approaches to realist sculpture, led Herbert Read to coin the term Geometry of Fear.

In 1955 Adams had an exhibition at the Victor Waddington Gallery in Dublin, and also showed at Rutgers University that same year. Included in the Whitechapel Gallery’s influential 1956 exhibition This is Tomorrow, he was a frequent visitor to St. Ives, where he met Michael Snow, and in 1975 became a member of the Penwith Society. In 1962 a retrospective of his work was held at the Venice Biennale; another retrospective took place at the Campden Academy in Northampton in 1971, followed by one at Liverpool Tate in 1982. Adams was commissioned to make several public sculptures, including, in 1973, a large steel work for Kingswell in Hampstead. Beginning in the 1960’s, he also produced lithographs with abstract geometric designs, such as Screen II. His work has been catalogued by Alistair Grieve, in Robert Adams 1917-1984: A Sculptor’s Record (Tate Gallery 1992) and The Sculpture of Robert Adams (Lund Humphries 1992).

Robert Adams’ work featured in the 2022 exhibition at the Barbican Gallery, Postwar Modern: New Art in Britain 1945-1965.

Text: Peter Murray

Editor: Francesca Flowers

All images subject to copyright.

Adrian Flowers Archive ©