(b. 5th September 1931)

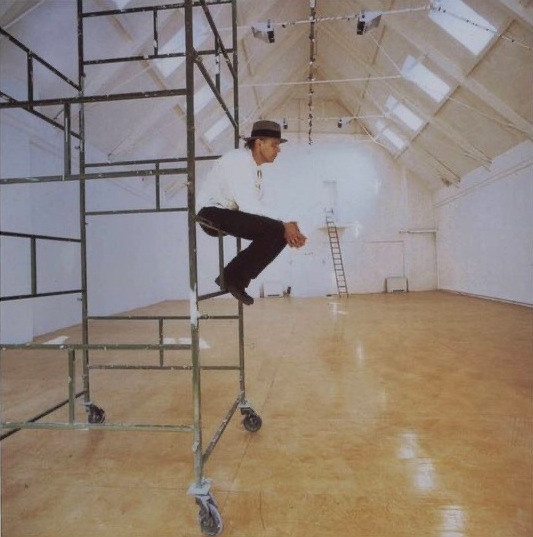

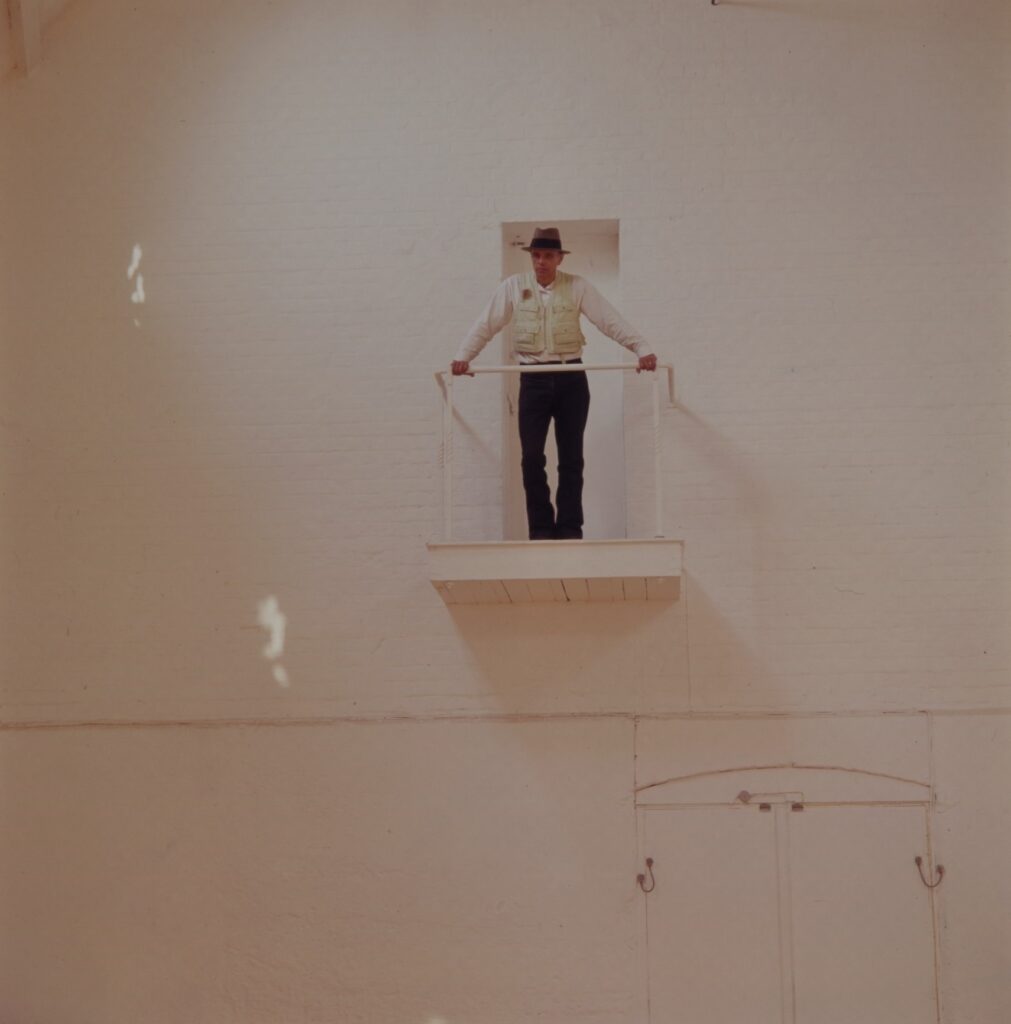

In 1956, Adrian Flowers visited the sculptor Brian Wall at his studio at Custom House Lane, Porthmeor in St. Ives. Using 120mm colour transparency stock, Flowers photographed a series of painted wood constructions by Wall, setting them up not in the studio but in the open air, on the flat sands of the beach. With titles such as Construction No. 1 and Construction No. 10, the modular black and white frames of these early works by Wall suggest the steel supports of Modernist buildings, while their inner panels, painted in primary colours, are in some ways the realisation in three-dimensional form of paintings by Mondrian.

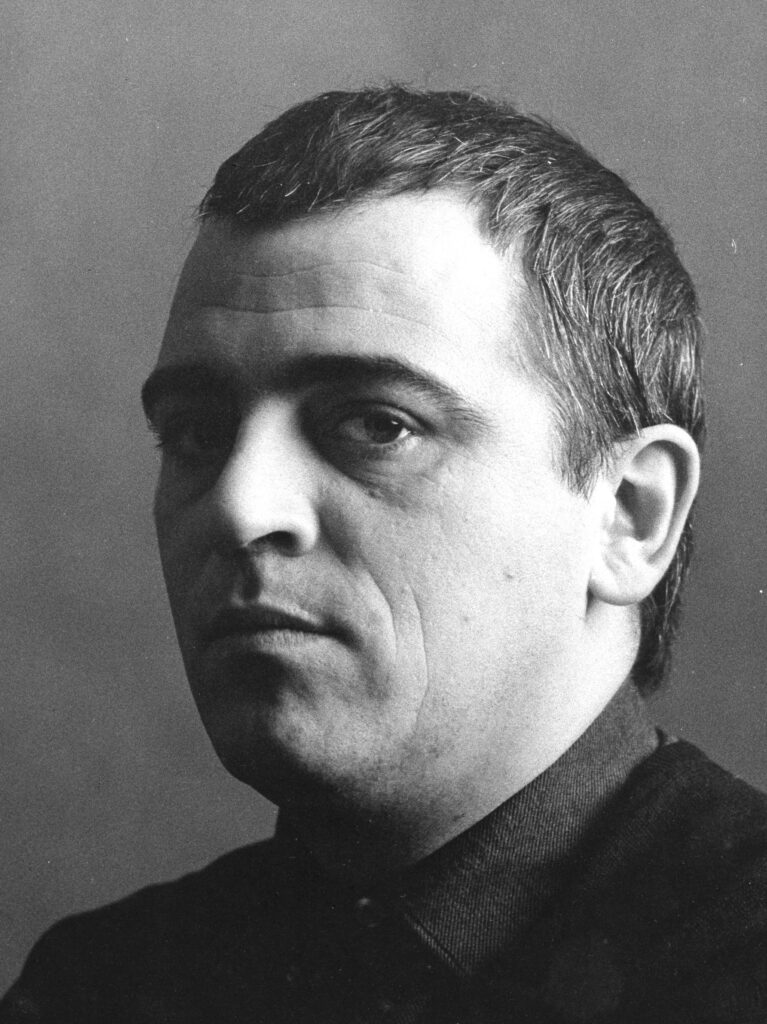

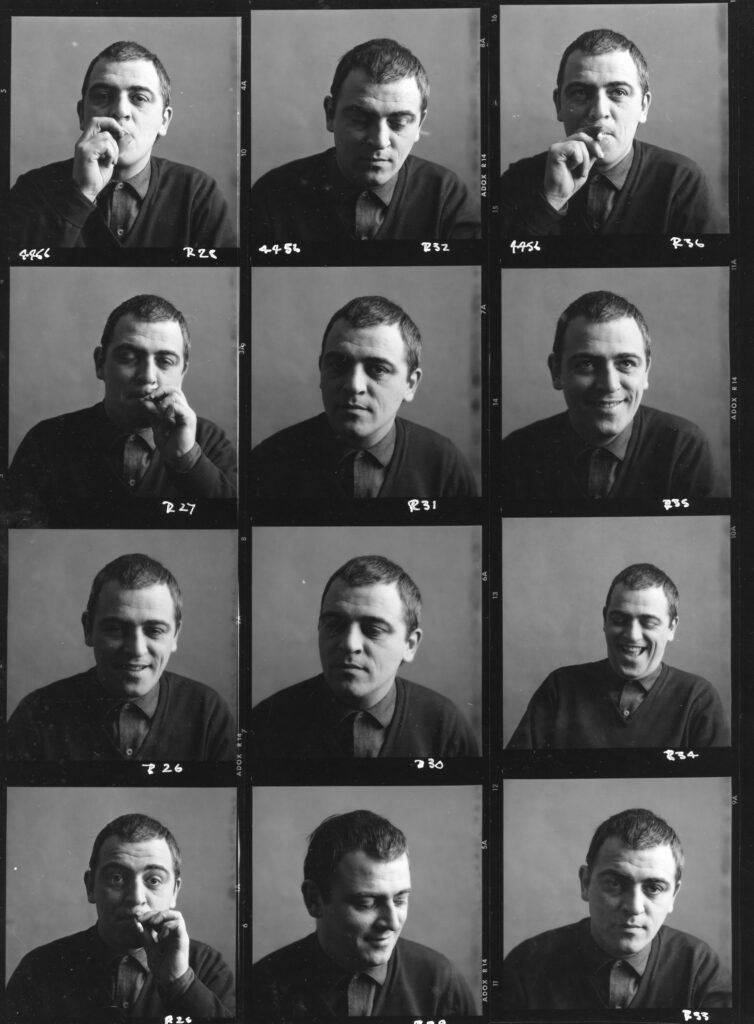

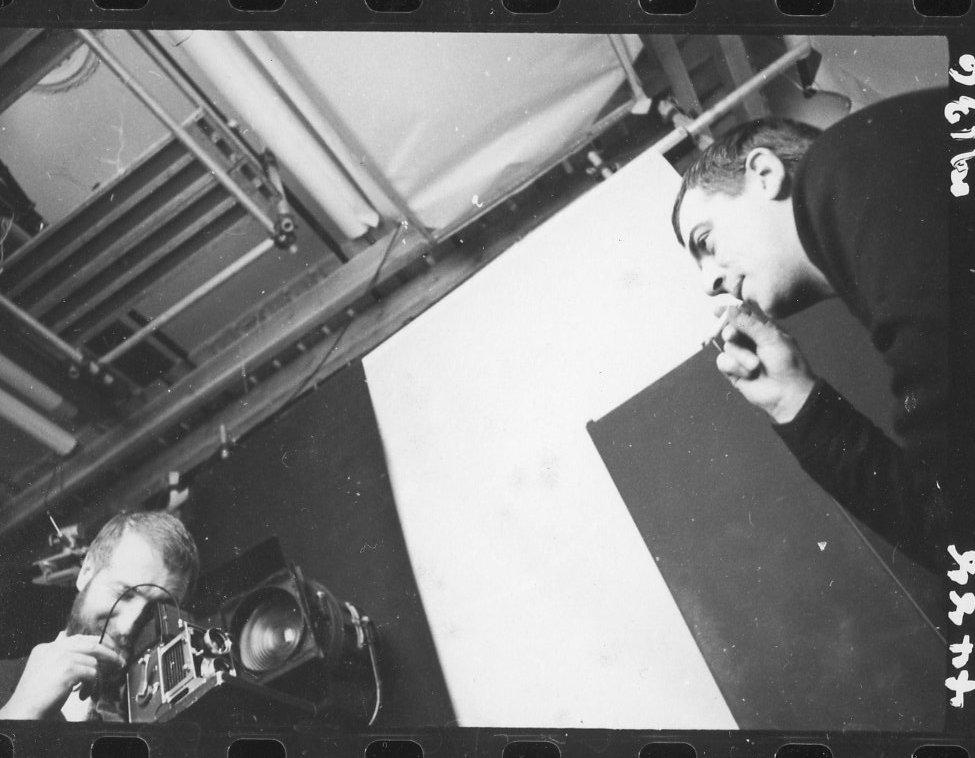

Flowers photographed Wall and his sculptures several times over the following decades. A sequence of black and white portrait shots taken in February 1963 show Wall assuming various poses; seated, in close-up, head and shoulders, smiling, smoking a cigarette, making funny expressions, hand under chin. He appears by turns thoughtful, quizzical, good-humoured, tough and determined. One sheet of contact prints shows him seated on a high stool. A folder [ref 4456] also contains several large-scale prints, made from these negatives.

Born in Paddington on 5th September 1931, Brian Wall’s childhood was spent in London, although during WWII he was evacuated to Yorkshire. After the war he left school, aged fourteen, to work as a glassblower in a factory. In 1949 he enlisted in the RAF for two years, where he trained as an aerial photographer (as had Adrian Flowers and Len Deighton), before enrolling at Luton College of Art. Deciding to become a painter, in 1954 Wall settled in St. Ives, where initially he worked at the Tregenna Castle Hotel. Shortly afterwards he met Peter Lanyon, who helped him find a studio in Custom House Lane, where Wall worked alongside Terry Frost, Patrick Heron and Sandra Blow. In 1955 he was introduced by Denis Mitchell to Barbara Hepworth, becoming her first studio assistant. He also met David Lewis, who had written on the work of Mondrian and Brancusi, and in 1956 was elected a member of the Penwith Society, exhibiting his work in the Society’s annual shows.

During these years, starting with the painted wood constructions, Wall developed his own sculpture practice, but quickly moved on making works in welded steel. The year after his first one-person show at the Architectural Association in 1957, he was included in the Arts Council exhibition Contemporary British Sculpture, and he also showed with the Drian and Grabowski galleries. In 1959, an article on his work was published in Architectural Design. Moving back to London, Wall became active in fine art education, serving on the National Council for Diplomas in Art and Design, and also on the Arts Council of Great Britain. In 1961-2, he taught at Ealing College of Art, before being appointed Head of Sculpture at the Central School of Art (now Central St. Martins), where William Turnbull and Barry Flanagan were also teaching. In 1961 Wall represented England at the 2nd Paris Biennale, and over the following years his work was shown in exhibitions throughout Britain. He featured in Bryan Robertson and John Russell’s 1965 Private View, a book documenting the rise of London as a centre for contemporary art.

A subsequent set of photographs [ref 5562] taken in London by Adrian Flowers record a series of medium and smaller sized welded steel sculptures by Wall, such as Untitled Steel Sculpture, Black 1964. Some were photographed in a studio setting, others in a laneway outside the artist’s studio. Several feature discs, and circles juxtaposed with straight pieces of steel, such as One Disc (1966); others are purely angular and geometric. Other photographs show the artist in his home, with family members, sculptures displayed on tables, and a geometric abstract painting on the wall.

In 1967 Wall had a solo exhibition at the Arnolfini Gallery in Bristol and was included in the Tate’s British Sculpture in the Sixties. On 25th March of the following year his Always Advancing, a large public sculpture in the form of two A’s, was sited at Thornaby-on-Tees in Yorkshire. In 1968, Wall’s sculptures were included in an exhibition organised by the Whitechapel Art Gallery, New British Painting and Sculpture, that toured to cities in North America, including Portland, Vancouver, Chicago, Houston and San Francisco. The artist visited the US several times, becoming friendly with Mark Rothko, Barnett Newman and the writer Clement Greenberg. In 1969, when the exhibition was shown at the art museum at Berkeley University, he was invited to become a visiting Professor there, and returned the following year, becoming a permanent faculty member in 1972. Although there were artists working in steel before Wall settled in San Francisco, they tended to work in less ‘pure’ modes. His presence in the area influenced several artists, including Fletcher Benton, to begin working directly, in a more abstract way, with welded steel. Taking up US citizenship, Wall became recognised more as an American sculptor and was appointed Chair of the Art Department at Berkeley, a post he held until his retirement in 1994. Throughout his teaching career, he continued to make his own work, setting up a studio and workshop in Oakland, where his assistant is the sculptor Grant Irish. He prefers to make his sculptures directly, working with pieces of steel on a one to one scale, rather than constructing maquettes, or working from drawings. This invests Wall’s work with qualities of lightness that are often absent in large-scale abstract metal sculptures. His pieces appear to teeter, tilt and turn. Circles, cylinders, I-beams and plates hover and jostle playfully. In spite of the massive scale, and the industrial materials he employs, there is a palpable pleasure and joy in his work.

Although Wall rejects the term “Constructivist” to describe his work—on the basis that his work does not relate to architecture, but emerges from a process of intuitive development—there is no mistaking the Central European and revolutionary Russian tradition of industrial materials used to make abstract art. This Constructivist tradition had been promoted in Cornwall during the war years by Naum Gabo, leading Ben Nicholson to adopt a pure minimalist approach to abstraction. Nicholson was an early influence on Wall who, from the outset, steered clear of the expressionist styles of Lynn Chadwick, Reg Butler and Kenneth Armitage, as well as the organic forms of Hepworth and Henry Moore.

A retrospective exhibition of Wall’s sculptures, organised by the Seattle Art Museum in 1982, toured to SFMoMa. The exhibition included two early St. Ives painted wood constructions; Metamorphosis (1955) and Right Angle Deck Construction with Vertical Movement (1956)—both revealing how close the artist had been to architecture at the outset of his career. Although most of the works in the Seattle show were from the 1960’s and 1970’s, including the brightly-painted Early Yellow (1975), there were more recent sculptures too, including October Jump (1981), in which two I-beam girders are supported by cylindrical and plate steel forms. Through the last four decades, Wall continued to exhibit in the UK, showing at Flowers Gallery in 2008 and 2011; he also showed with Flowers in Los Angeles, Max Hutchinson in New York, and with John Berggruen and Hackett Mills in San Francisco. In 2006, a monograph on his work, written by Chris Stephens, was published by Momentum Press 2006, and in 2014 Wall established a foundation to benefit working artists. As recently as 2015 a solo show held at the de Saisset Museum at Santa Clara University featured sculptures monumental in scale but light in feeling, reflecting Wall’s interest in Zen Buddhism—an interest which began in St. Ives in the 1950’s, and continues to inspire his work to the present day.

Text: Peter Murray

Editor: Francesca Flowers

All images subject to copyright.

Adrian Flowers Archive ©

For further reading, refer to Brian Wall by Chris Stephens, Suzaan Boettger and Barry Munitz. Momentum publishing 2006.