by Matthew Flowers

He was eccentric. To the extent that when I was born in 1956, two weeks late and almost 10 pounds, Adrian’s primary concern at the birth was getting a good sound recording of the action. Despite the fact that I was silent on arrival, my mother was certainly not, when she brought me into this world. As soon as things had calmed down in the kitchen of England’s Lane, Haverstock Hill, above the electrical shop, Adrian’s first inclination was to go upstairs and relive the experience through the recording.

Like many of us, Adrian was full of contradictions. A man who expressed zero interest in sport, yet was quietly, and highly, competitive. He ensured we always had the biggest firework displays amongst our friends. When I was 7 he visited me at boarding school on sports day. Consuming biscuits as part of a race against parents to see who could eat the quickest, he made sure he won. But as with all Flowers, he would never leave a plate with food left on it anyway.

Adrian had a lifelong interest in music, particularly jazz, and he was an exceptional talent at the piano. At Sherborne, the headmaster reported to his father Edward that Adrian was distracted from his academic studies by his interest in playing the piano. Edward had already been disappointed by the vocational fate of Geoffrey, Adrian’s brother, who became a piano teacher, organist and composer. Edward advised the headmaster to put a stop to Adrian’s piano playing. Adrian made up for that disappointment by facilitating and encouraging all four of his children to become fine musicians themselves.

He loved cats. There was always at least one cat in all of his households. But the greatest animal love of his life was Sarah the dog, a beautiful Labrador-boxer whose football skills matched George Best and who was the subject of many photographic portraits. Named after the jazz singer Sarah Vaughan, Sarah was the catalyst to Adrian’s other great pastime – walking and talking on Hampstead Heath. He instigated a Sunday morning tradition of walks on the Heath with Sarah and any family that was around.

After the walks were yet more talks. Adrian gathered many artist friends to our house on Patshull Road later on Sundays. He had a love of British constructivist art – Kenneth Martin, Anthony Hill, John Ernest, Victor Pasmore. He placed sculpture by Denis Mitchell and Brian Wall in our house. When Adrian rubbed the tall metal curve of the Mitchell piece, money would mysteriously fall to the floor. I have less fond memories of Brian Wall’s heavy steel construction. One day a strong friend of Adam’s tied a rope through its metal bars, pulled it to the floor, catching the end of my foot in the process and breaking my toe.

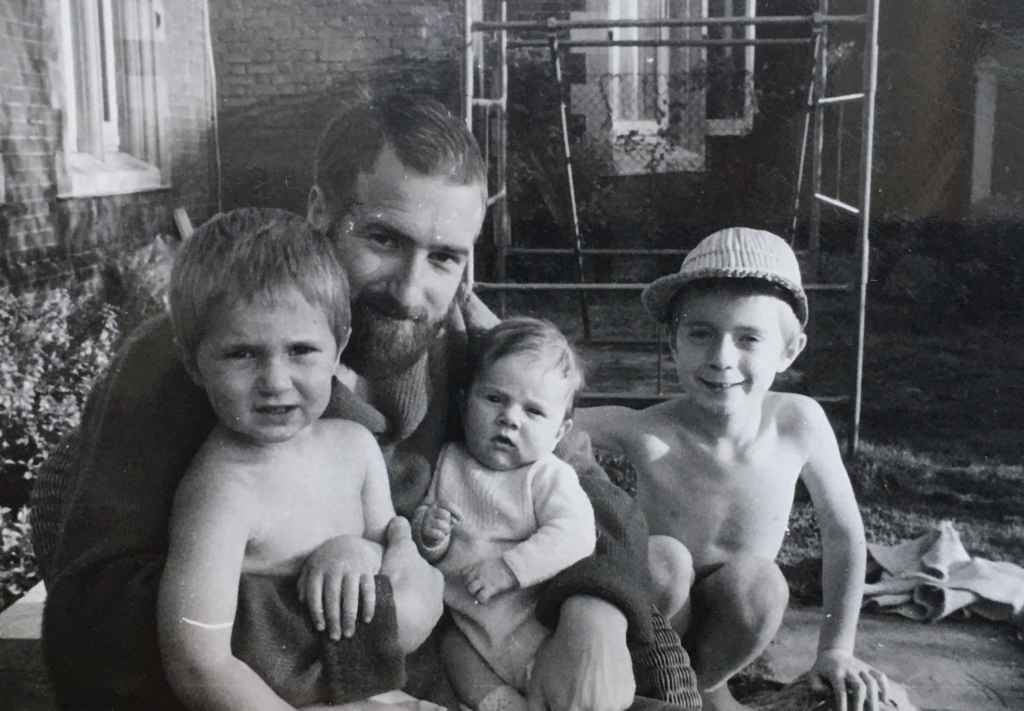

A happier memory from my childhood was the game Adrian played with us loosely titled “Sit Still.” We were called to Adrian’s lap to sit perfectly still on his knee otherwise we’d be dropped to the floor. Somehow, we all always ended up on the floor.

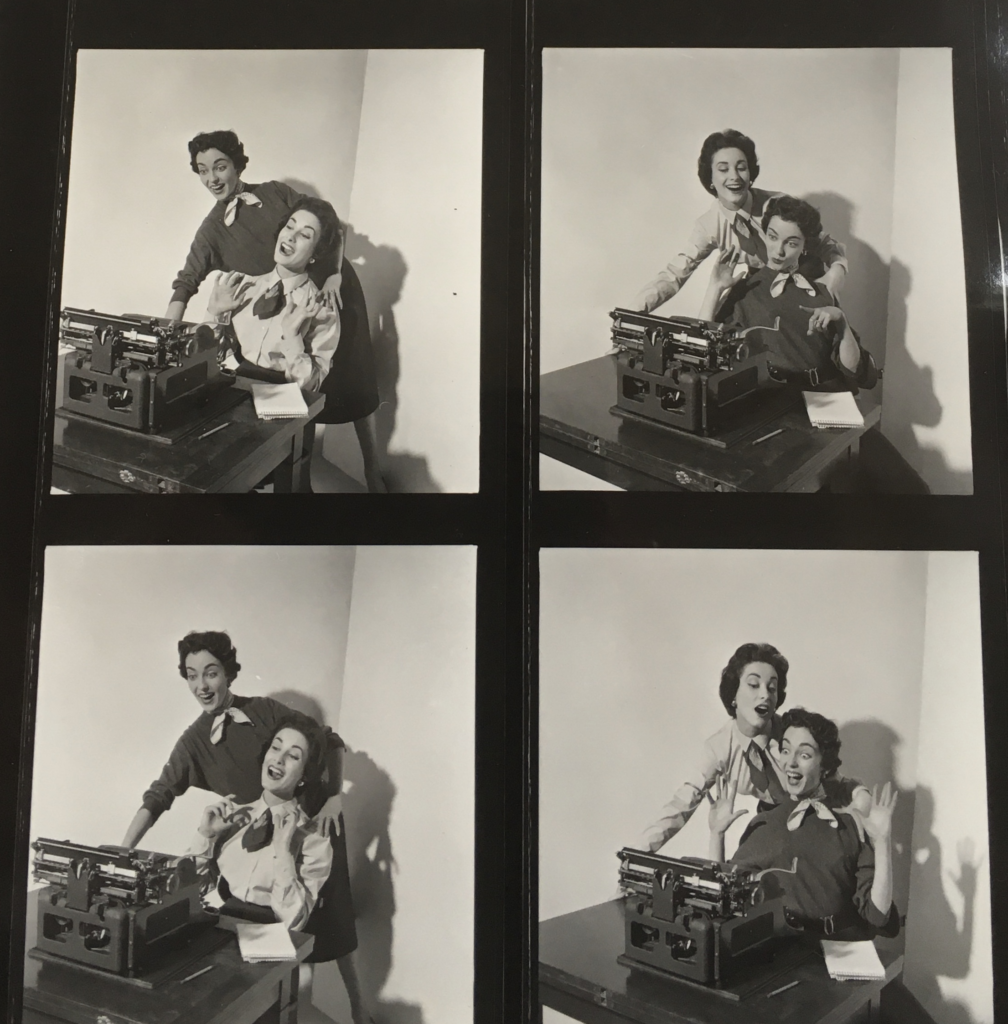

He believed in the power of advertising and was sometimes obsessive in pursuit of the perfect image. When commissioned for what I recall was a legwear advertisement, he searched long and hard for the “ideal knees,” and had countless women in his studio showing him their legs, none of which fit the bill. In exasperation he finally asked his assistant Gala to show him her knees, and had his Eureka moment that the perfect knees were right in front of him. Gala’s knees became the subject of a famous postcard commissioned by Angela Flowers Gallery for their 1971 postcard exhibition.

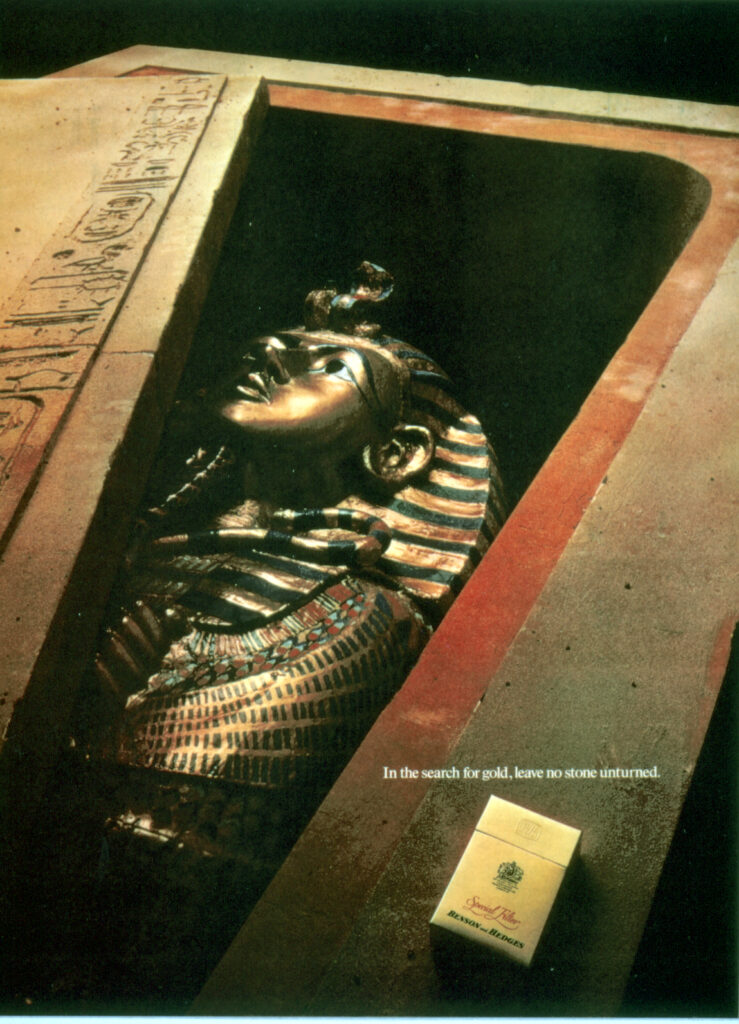

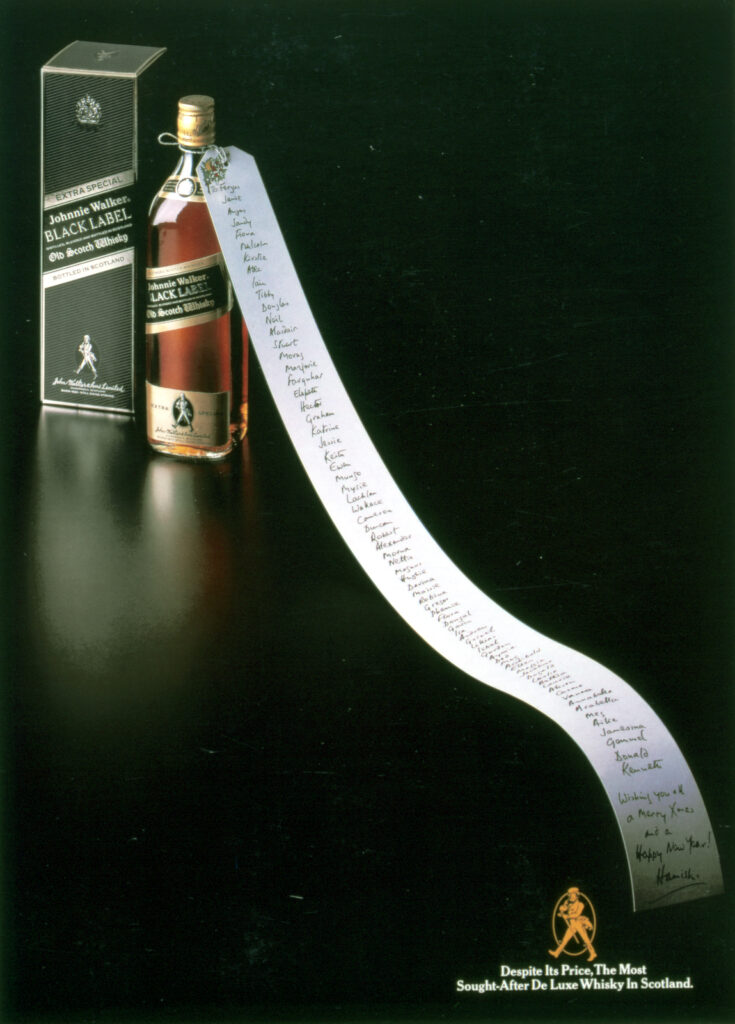

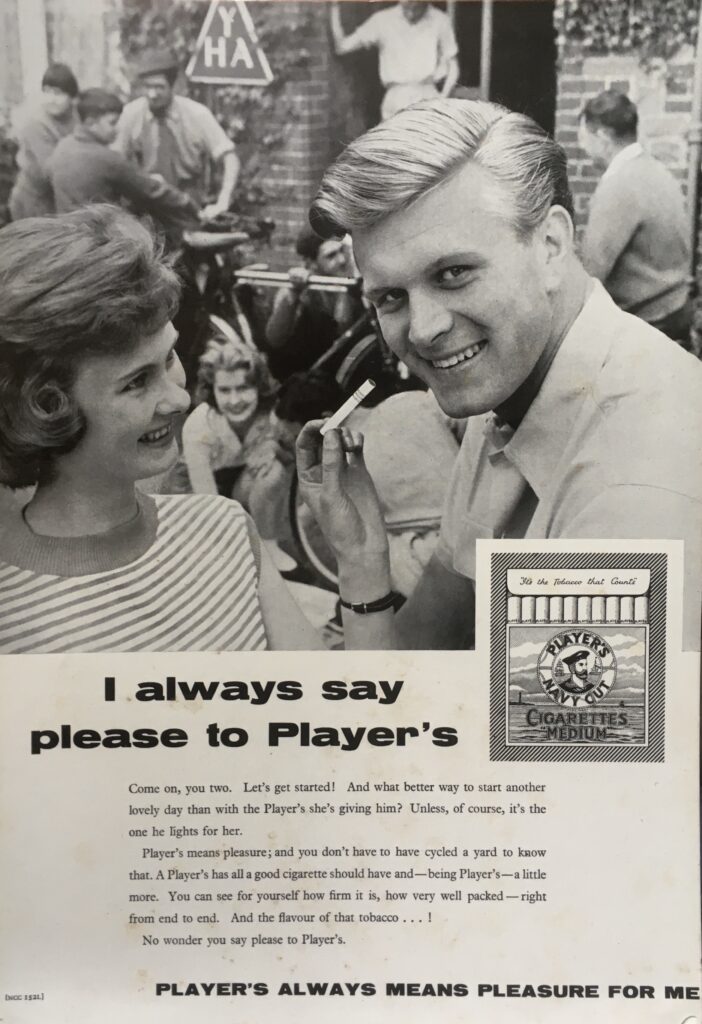

We were often the beneficiaries of the props leftover from Adrian’s sets. When Adrian would do cigarette ads, he would come home with cartons of cigarettes, which Dan and I would steal on a regular basis. He once did an ad for an ice cream company that had 32 different flavors. He created a photograph of 4 cones, each with 8 scoops of ice cream on it. He brought home the remaining ice cream from the set to our delight.

A little known passion of his was boating. His childhood in Portsmouth was a likely start for this. When I was about seven he bought a boat called Edith 2. Our family took a memorable trip on her from London up the Thames to Pangbourne. He took Edith 2 from London to Mill Cove, county Cork, in the late 60s. Edith 2 had an inbuilt motor which made the boat heavy. I was charged with going down at dawn to bail out any overnight water ingress. When I got there, there was no sign of Edith. She had sunk to the bottom of the cove. On another boat, I spent a week on the Norfolk Broads with him during the summer of 1973. It was a happy trip for me.

Over the years Adrian had many Alvis cars, culminating in two giant saloons, both blue. The reason he had two was that one was always in the garage being fixed. Soon after I passed my driving test I was allowed to drive one on my own. It was like driving a tank.

He idolized his three siblings, all of whom were significantly older than him. He only got to know some of his nieces and nephews as adults, many of whom visited him here in France.

He came to France in 1996, with Françoise. He loved the sun, good food, and a quieter life than London. He never learned French.

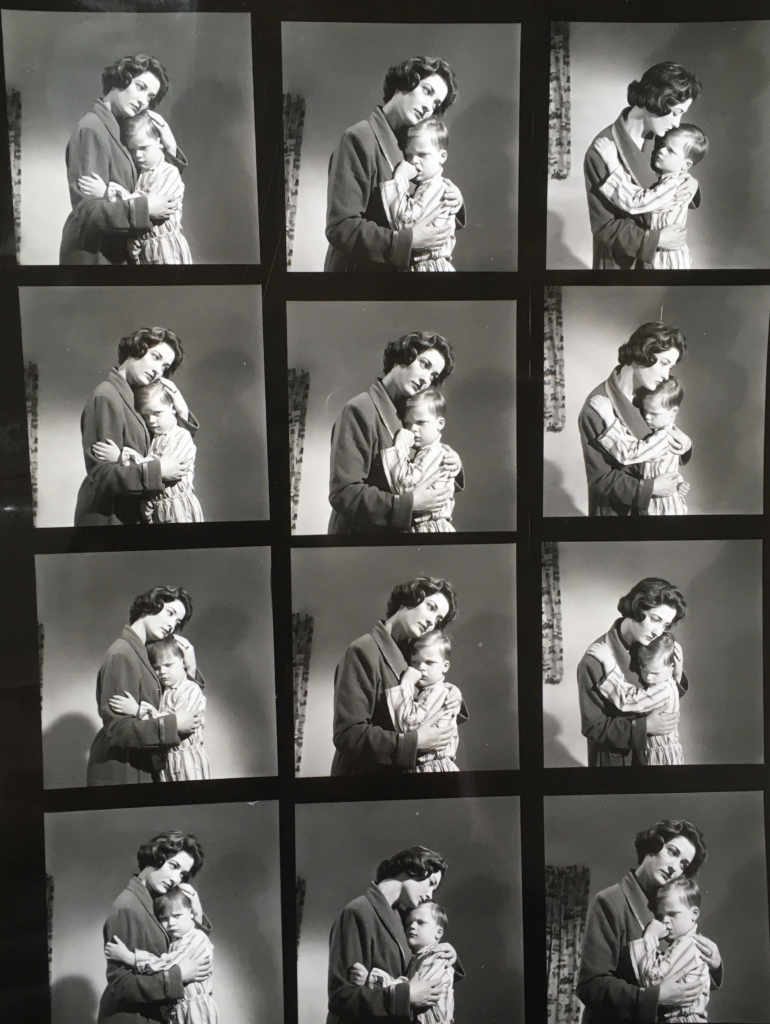

The Moulin allowed him the opportunity to create his archive in the famous barn, with the help of Brian Durling, who is here today. The barn was the culmination of his life’s work. It was Adrian’s personal museum, library, oasis, office, studio, escape, home, legacy and spirit. He cherished every single item in the barn, from his rare vintage cameras, lights, tripods, scaffolding, magazine and newspaper collections, set props, preparatory materials from adverts, negatives, transparencies, polaroids, prints, printing equipment, posters, artworks, video tapes, books, portfolios, objects that he wanted to photograph, like old metal, tree trunks, pieces of wood, rotting fruits. Nothing escaped his eye, and nothing escaped from the barn. He was fiercely protective of its contents. On many occasions over the last ten years I tried to borrow various items with a view to formally cataloguing his remarkable career and rare archive. He was insistent that nothing be removed, dismantled or dispersed for any purpose by anyone.

Over the last week I’ve had many kind messages from people who have known Adrian. Len Deighton who knew Adrian well through being RAF photographers together just after the second world war, said “I want to assure you that your father was very philosophical about everything. So don’t be sad on his behalf. He will have taken death in his stride, as he did everything else.”

A few memories and reflections others have shared have stood out as well: dentist’s chair, spooky fishtank, end of an era, eccentric individual, individual, master of his Life hobby, profession and innovator extraordinaire, the holder of waddery, all his paperwork, the Stuff Merchant of Tite Street, garages galore, giggling at the Marx brothers, being a great husband, a brilliant father and a wonderful grandfather.

Matt Flowers

May 2016