Photograph by Adrian Flowers

Beginning in July 1954, Adrian and Angela Flowers, and their year-old son Adam, made the first of what was to become a series of regular visits to St. Ives. Setting out to photograph the artists and writers who had made the town famous, during this first visit Adrian also photographed other aspects of Cornish life, including carpenters at work and a traditional mummer.

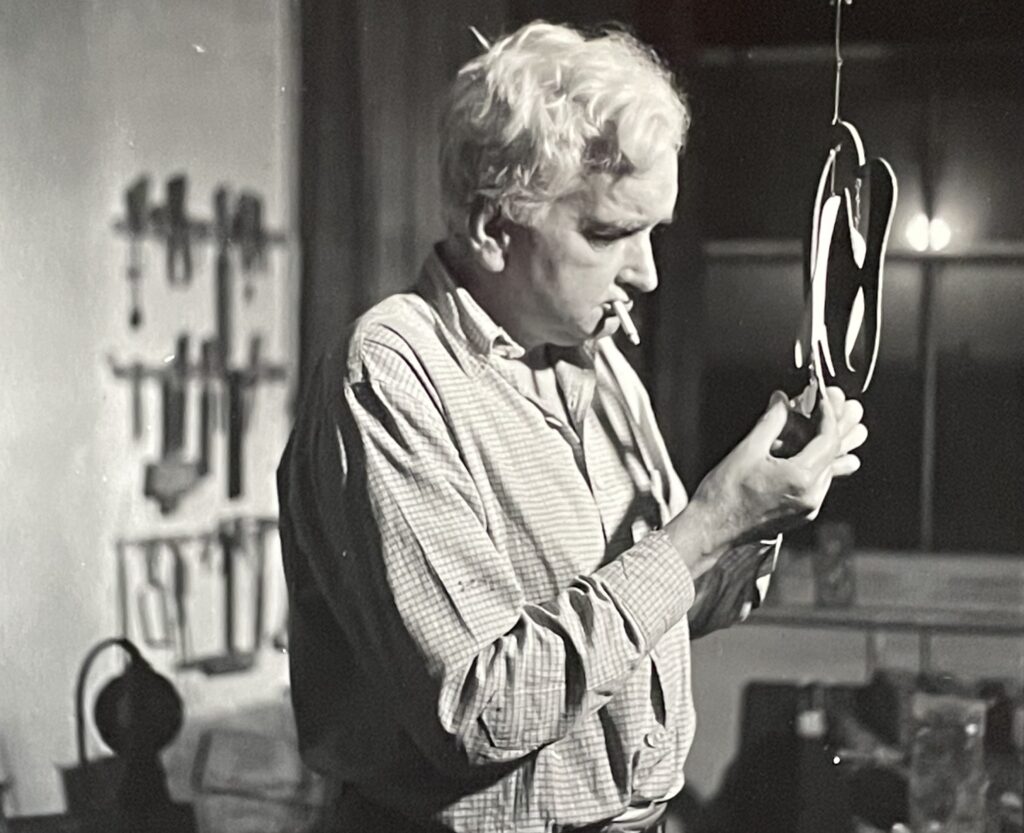

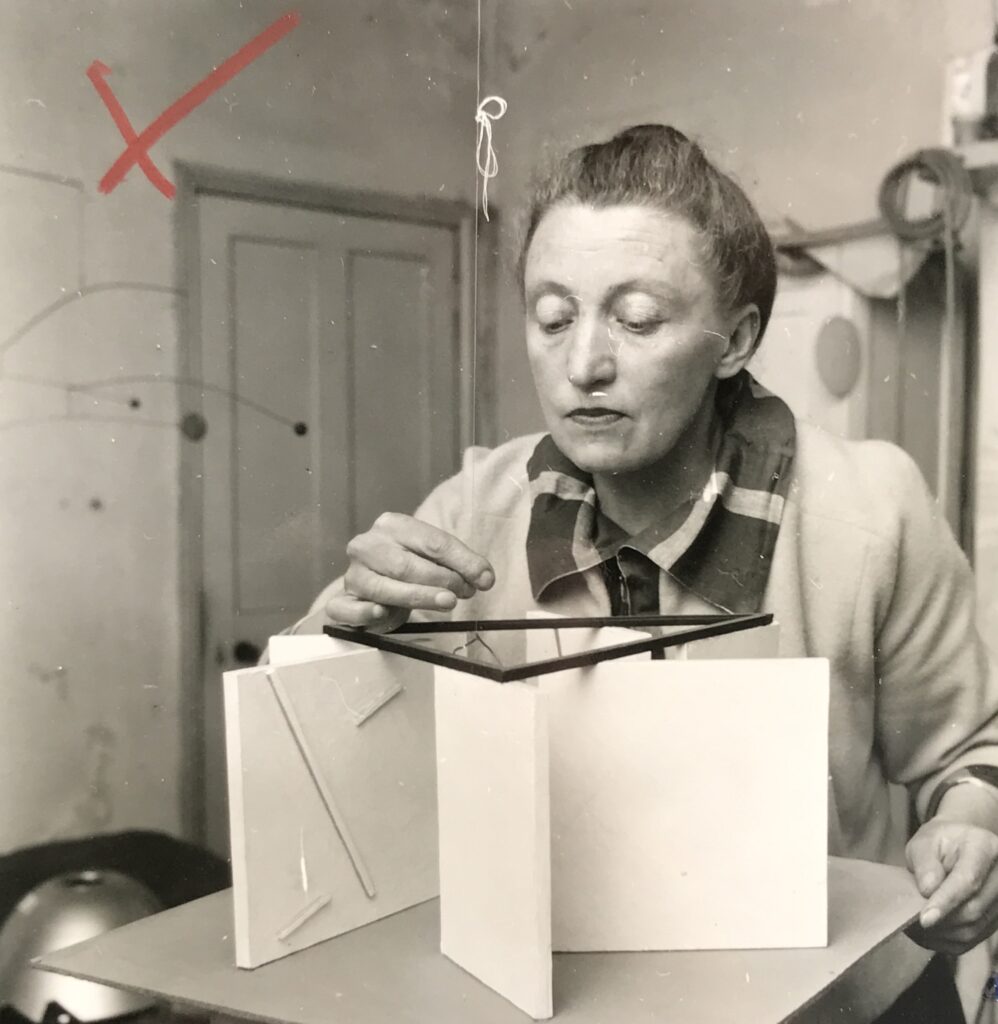

Denis Mitchell (1912 – 1993)

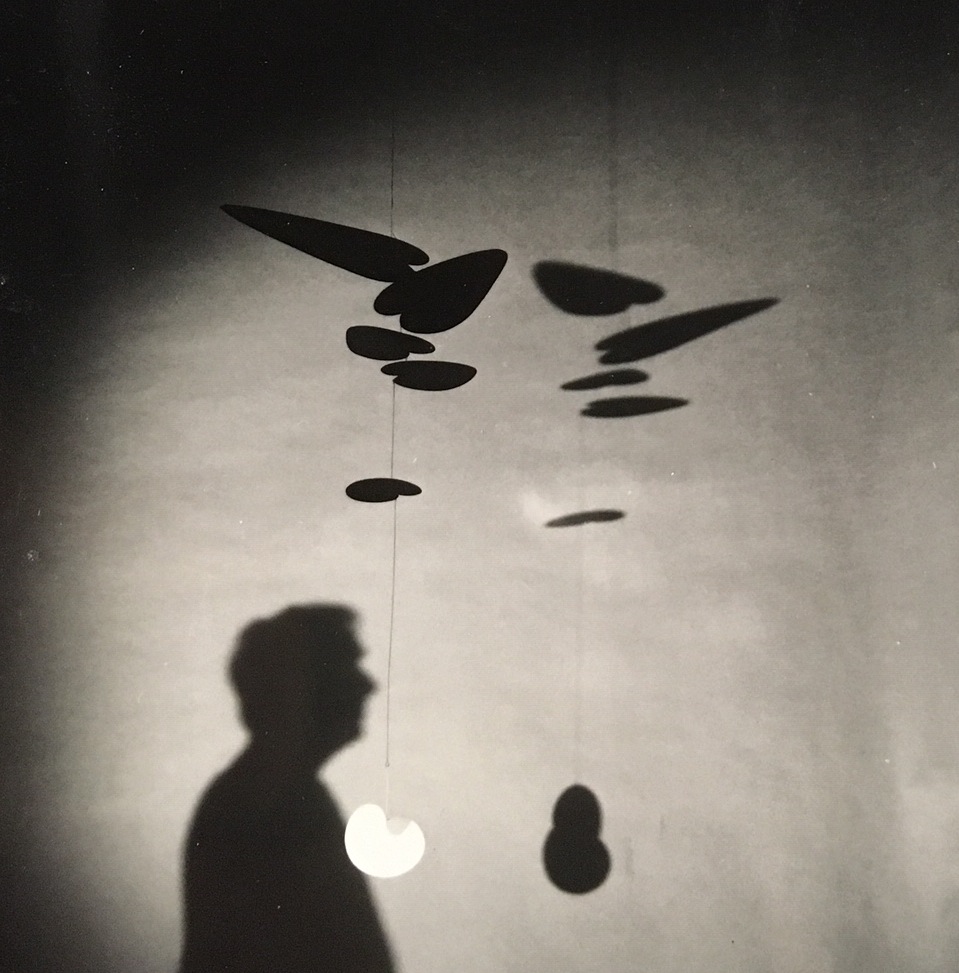

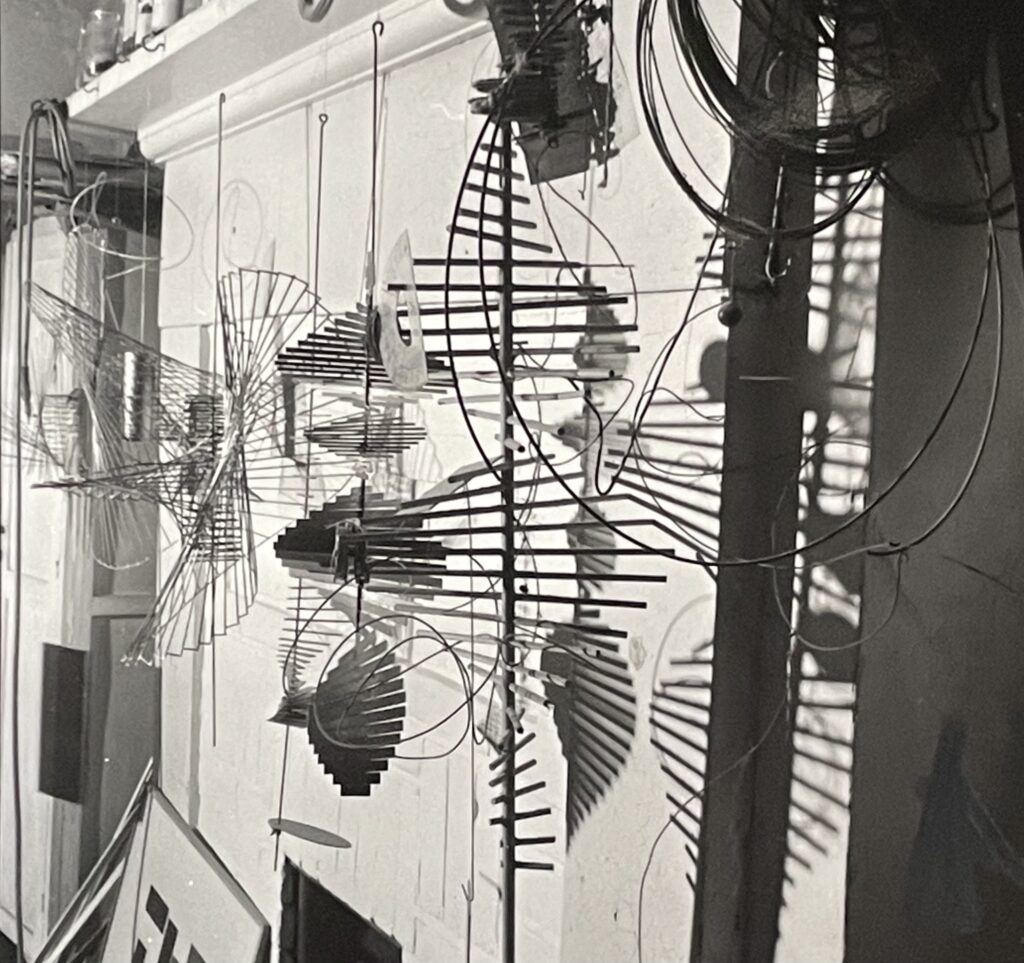

A sequence of photographs document the studio of Denis Mitchell. An abstract sculptor, working mainly in wood and bronze, Mitchell was an early member of the St. Ives group, having moved to Cornwall from Wales in 1930. Located in the former workshop of plumbers W. F. Smithson, his studio was a timber and corrugated iron building, in a cobbled courtyard off one of the town’s narrow streets. The entrance was decorated with abstract paint marks, perhaps made by Mitchell himself. Upstairs, the interior contained a cast iron stove, workbenches and timber sculptures. The whitewashed walls were decorated with paintings, antelope antlers and an African mask. At the side of the studio was an improvised rack for holding lengths of timber.

Photograph by Adrian Flowers

Present that September day were Mitchell, Stanley Dorfman and Terry Frost. Angela and young Adam were there also. Mitchell, then in his early ‘40s, was photographed sitting in an Victorian armchair, hand under chin, looking grave and thoughtful. Since moving to Cornwall twenty-four years earlier, he and his brother Endell had contrived to make a living in St. Ives, renovating houses and growing vegetables and flowers. St. Ives was famous for its early spring flowers, violets and the yellow narcissus Soleil D’or. In 1938 Endell became landlord of the Castle Inn on Fore Street, the pub that was later to be the birthplace of the Penwith Society. Around this time Denis, working in a craft market, met Jane Stevens; they married in 1939 and were to have three daughters. During WWII, Mitchell worked in the local tin mines, learning to hew stone deep in the narrow mine shafts. He also served in the Home Guard, where he met the potter Bernard Leach and art critic Adrian Stokes. Encouraged by Leach, in 1946 Mitchell joined the St. Ives Society of Artists, and three years later was taken on as an assistant by Barbara Hepworth at Trewyn Studio. When Adrian photographed him, he had been working with Hepworth for five years, learning the art and craft of abstract sculpture. In 1955 he became chairman of the Penwith Society, and later joined John Wells at his Trewarveneth Studio in Newlyn. Mitchell is credited with inspiring many younger artists, including Broen O’Casey and Conor Fallon. Another photograph by Adrian shows Dorfman and Mitchell standing together in the studio, with Frost descending the staircase. This introduction to the artists of St. Ives ultimately led Angela, some years later, to open her first gallery in London. For two decades Mitchell was one of her leading artists. A major exhibition of his work opened at the Angela Flowers Gallery in March 1993, just before his death.

Photograph by Adrian Flowers

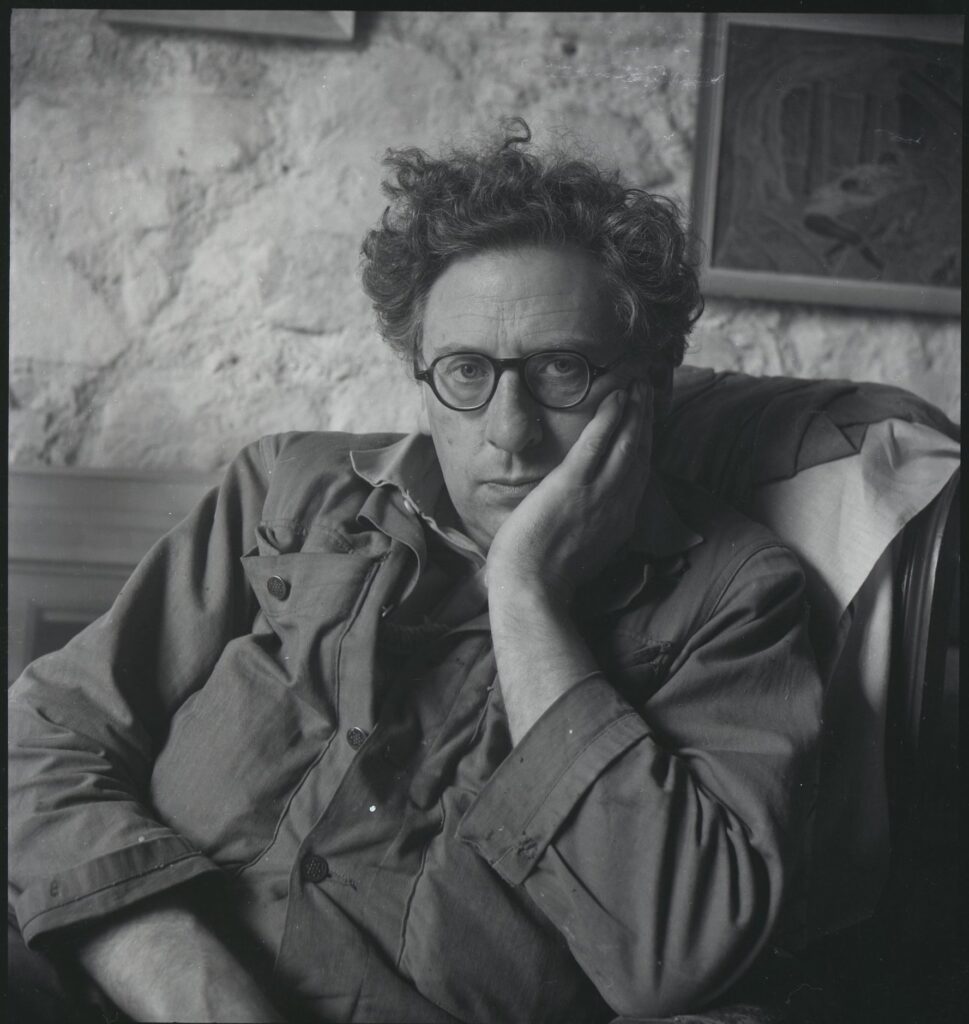

Stanley Dorfman

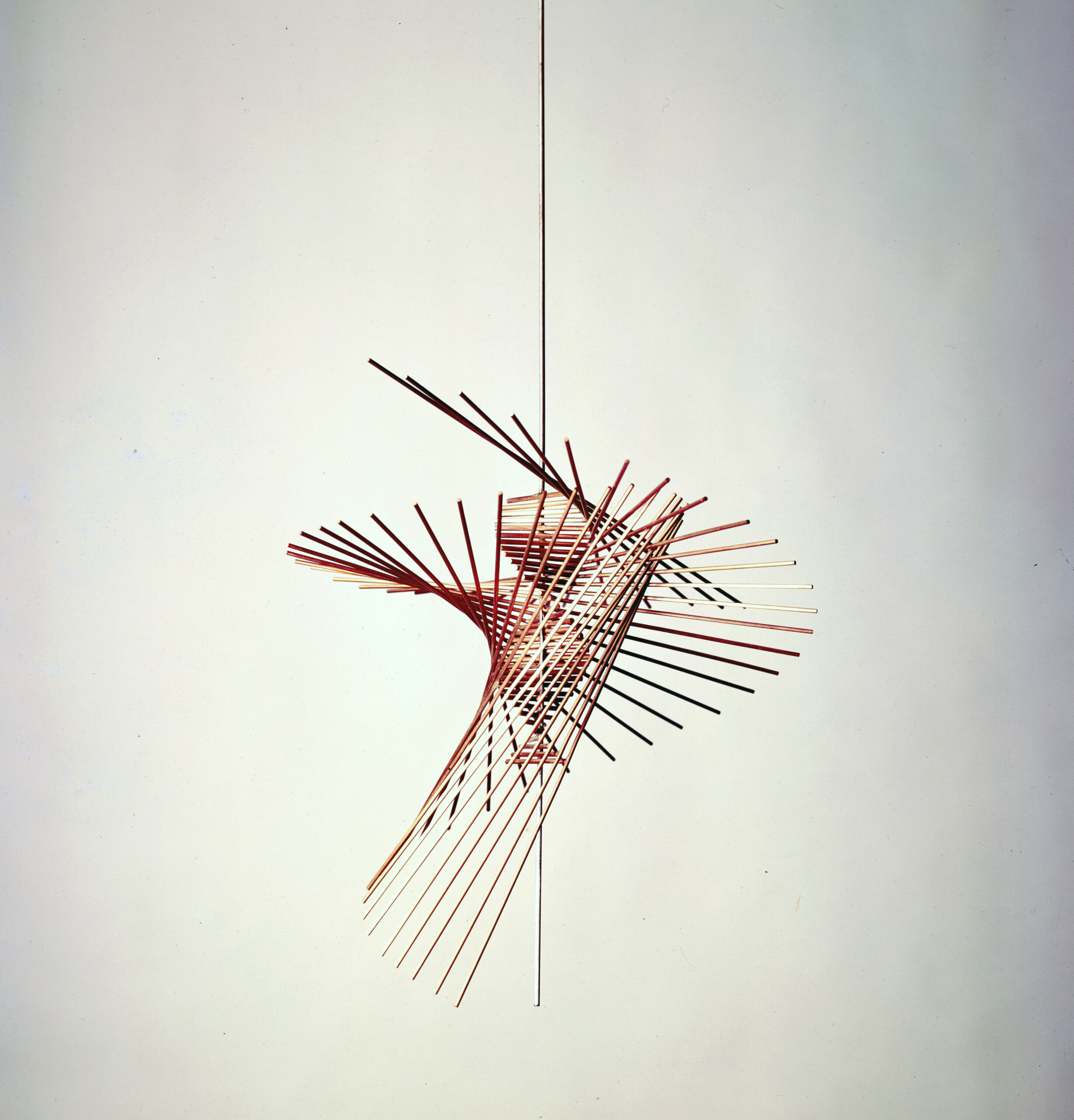

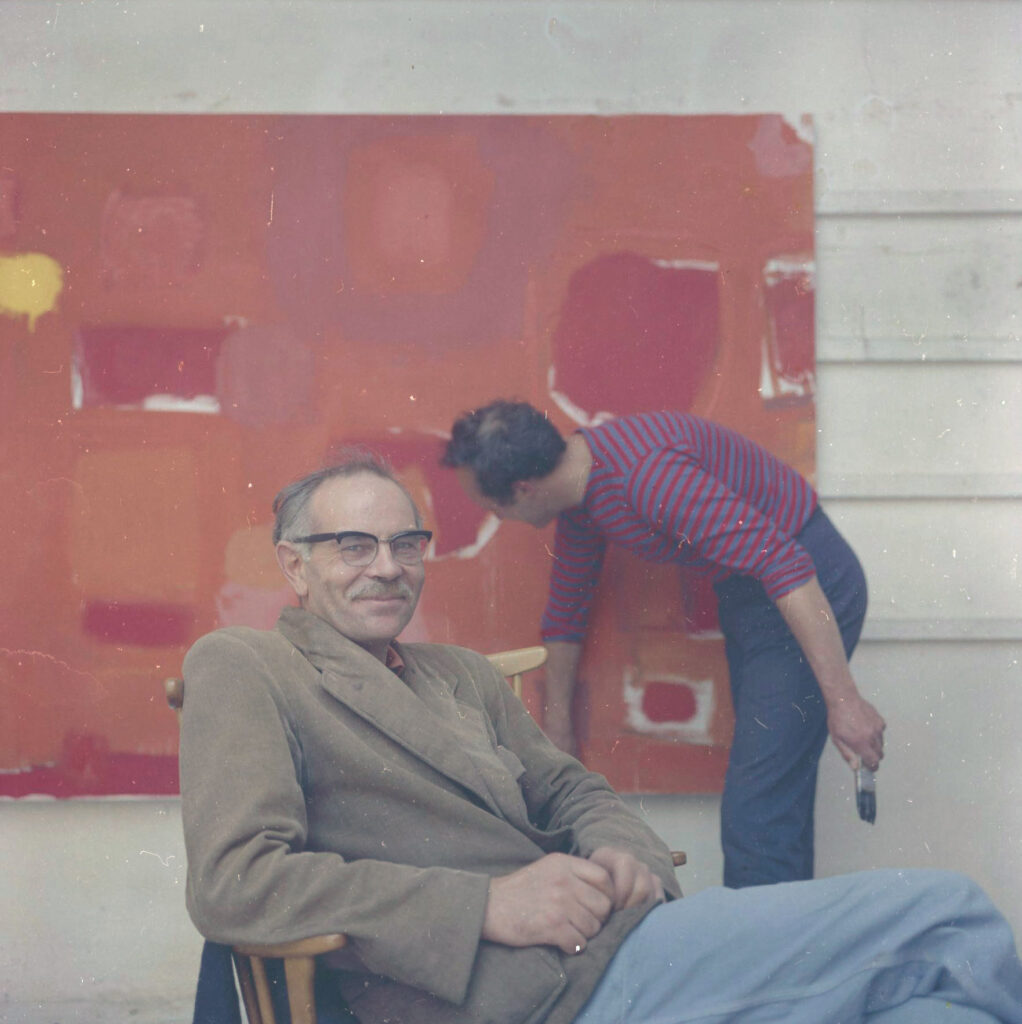

A television and film producer, renowned for introducing Top of the Pops to BBC audiences in the 1960’s, Stanley Dorfman was born in Johannesburg, South Africa. Aged nineteen he began to study architecture, but switched instead to fine art and in 1946 was awarded a scholarship to the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris. After spending six years in France, Dorfman and his wife and children went back to South Africa to see his parents, but they found the political system there repellent. In 1954, he moved to England, settling in the artists’ colony of St. Ives, where he worked as a studio assistant to Barbara Hepworth, while continuing to develop his own art. His wife and children remained in South Africa until Dorfman could afford to bring them to Europe. His paintings from this early period are hard-edged abstract works, with strong flat colours and titles such as Vertical St. Ives (Paul), Blue and Brown Study, and Composition with Four Rectangles. His 1954 painting Across the Bay features abstracted hard-edge waves.

He also created three-dimensional panels which, while paying homage to Mondrian and De Stijl, hark back to mosaic designs and wall pieces he had made in South Africa. In South Africa also, Dorfman had organised music concerts, featuring jazz musicians. This interest in music remained with him, and in 1964 he left St. Ives to work as an art director with BBC television, then as producer and director of the popular weekly music programme Top of the Pops. Meeting Dick Clark who had travelled from the United States to England in search of new talent, Dorfman began to alternate between New York and London. He a created a series for the BBC called ‘In Concert’, beginning with Randy Newman, and followed by Joni Mitchell. In 1968 he had Leonard Cohen on the show. During his long career in British film and television, Dorfman directed over two hundred shows, with musicians such as the Beatles, Rolling Stones, Elton John and David Bowie. In 1974 he decided to relocate to Los Angeles, where he directed and produced music videos for many artists, from Robert Plant to Emmy Lou Harris. He took over Dick Clark’s In Concert series and also worked with Yoko Ono on videos, made using footage taken by John Lennon. He collaborated with David Bowie on two videos, Be My Wife and Heroes, both from 1977, and both in the collection of MoMA. After a career as music producer and director, Dorfman returned to painting. His later works, more lyrical and painterly, often reference music, as in La Bamba and Imagine. His partner of some forty years is the actor Barbara Flood. Dorfman currently lives in Los Angeles, and exhibits his paintings there at The Lodge gallery.

Photograph by Adrian Flowers

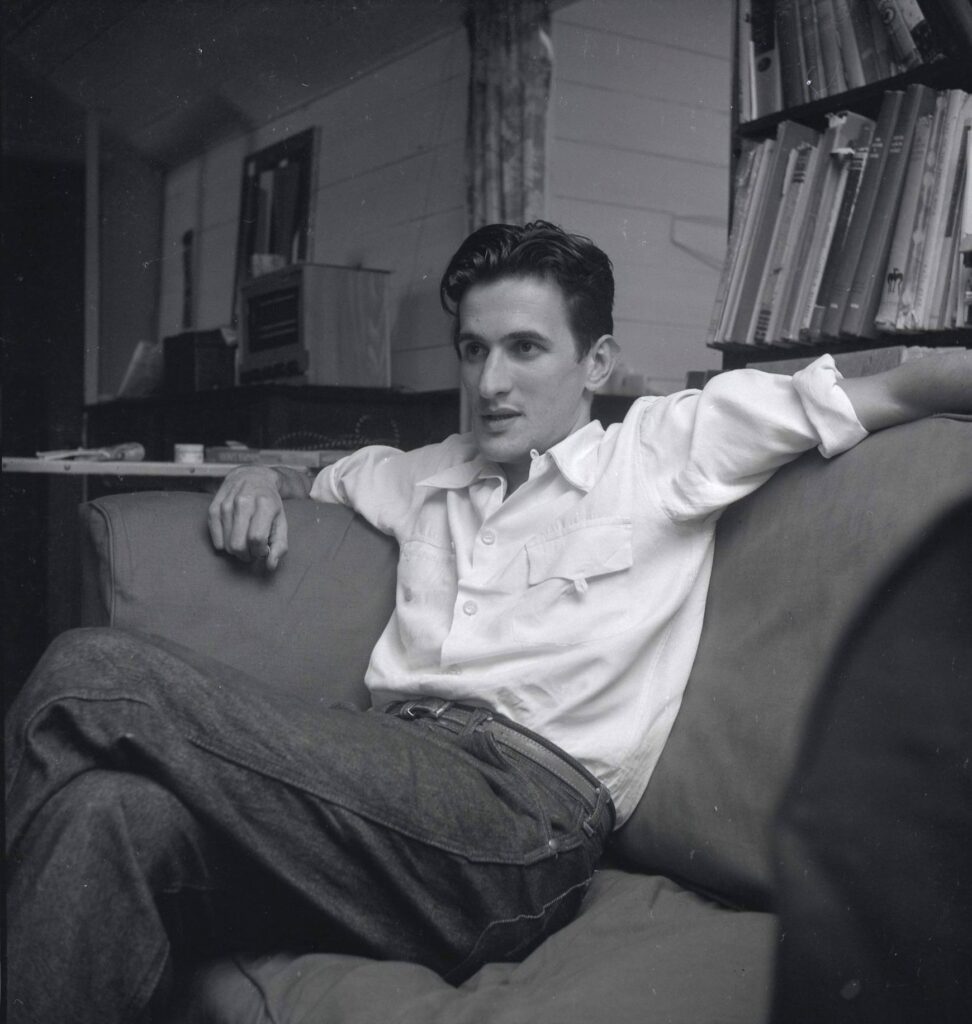

Terry Frost (1915 – 2003)

A second visit by the Flowers family to St. Ives followed in December 1954, and a subsequent visit in May 1956, when Adrian photographed Terry and Kathleen Frost, with their young sons Adrian and Anthony. The group assembled on Smeaton’s Pier, with the harbour and Wharf in the background. Terry’s warm and convivial personality shines through in these images. He and Kath took raising a large family in their stride. He would often get up at 6am, to take the toddlers for a walk on the quay. In one shot, he holds up Anthony, while pointing to the sky.

Photograph by Adrian Flowers

Born in Leamington Spa, Warwickshire in 1915, Frost had led a varied life before coming to St. Ives. The son of an artilleryman, he left school aged fourteen to work first at a cycle repair shop, then at Armstrong-Whitworth, the company renowned for its battleships and locomotives (and also for the universal ‘Whitworth’ thread that standardised nuts and bolts). By the time Frost went to work for the company at Coventry, it was called Vickers-Armstrong, and was making Whitley bombers, on the wings and fuselages of which he painted RAF roundels. Having enlisted in the Territorials, during WWII Frost served in France, Palestine and Greece. Fighting with the commandos in Crete in June 1941, he was taken prisoner and spent the rest of the war in POW camps. At Stalag 383 in Bavaria, he found he had a talent for sketching portraits of fellow prisoners, using canvases made from hessian pillowcases, primed with glue size made from barley soup. The brushes were made from horsehair. He painted around two hundred portraits, and also met the artist Adrian Heath who encouraged him to take up painting as a profession. Having studied with Stanhope Forbes in Newlyn, Heath was familiar with Cornwall and its tradition of welcoming artists. Frost credited the semi-starvation he experienced during the war as helping him achieve a higher level of spiritual awareness; this no doubt contributed to the qualities of alertness and intellectual presence that characterise his art in the post-war period.

After the war, on returning to England, Frost enrolled firstly at the Birmingham College of Art, then at Camberwell School of Art. In 1945, he married Kathleen Clarke, who had worked in aircraft factory during the war. The following year, forgoing a job as a lightbulb salesman, and availing of his soldiers’ back pay that had built up during years of imprisonment, he moved to St. Ives with Kath and their first-born son. They lived in Headland Row, overlooking Porthmeor beach, while he attended the St. Ives School of Art, and also worked in a café to make ends meet. The St. Ives School was run by Leonard Fuller and Marjorie Mostyn, both dedicated artists: Fuller painted a portrait of Terry Frost with his young son on his knee. In 1947 Frost’s first exhibition Paintings with Knife and Brush was held at Downing’s bookshop. Returning to Camberwell in 1948, he studied under Victor Pasmore, Ben Nicholson and William Coldstream. Pasmore was at this time moving towards abstraction, and Frost followed his lead. Although Madrigal, his first abstract painting, dates from 1949, when the Frosts were back living at 12 Quay Street, on the St. Ives seafront, it is the Cubist-inspired Walk along the Quay, painted the following year, that is regarded as his breakthrough, its bold composition dominated by semi-circles, interrupted by vertical linear areas of blue and khaki green. Walk Along the Quay is the first in a series of paintings, done on hardboard, that show an increasing confidence with abstraction. Another work from this period, Brown and Yellow (c1951-2), is in the Tate collection (although the Tate was initially slow to acquire a work by Frost). Many of his paintings from these years suggest draped fabrics, or the Cornish landscape with long fields terminating in angular cliff edges, as in Blue Winter (1956). Frost showed for three years with the St Ives Society of Artists, and was elected a member of the more progressive Penwith Society. For many years he made prints with Hugh Stoneman. During the 1950’s he exhibited regularly with the Leicester Galleries in London and also taught at Bath Academy, the University of Leeds, and in Cyprus. Although Frost joined the London Group in 1958, over the following decade a new generation of mostly London-based artist came to the fore. As sales of his work flagged, he ceased to show with the Waddington Gallery, and increasingly turned to teaching to help support the family, while continuing to pursue his own art. After Leeds, the Frosts moved to Banbury, Oxfordshire, where they lived between 1963 and 1974, with Terry lecturing at the University of Reading. In the early 1960’s he undertook a residency at San Jose in California, experimenting with new acrylic paints, and also teaching at the University of California. He showed in New York, beginning with the Barbara Schaeffer gallery in 1960, where he met Mark Rothko and other leading artists.

In 1992, Frost was elected a Royal Academician and six years later was knighted. He and Kath had six children in all: five sons, Adrian, Anthony, Matthew, Stephen and Simon, and one daughter, Kate. Stephen is an actor, while Adrian and Anthony followed in their father’s footsteps as artists; Anthony still lives and working in St. Ives. When Alan Bowness was appointed director of Tate, he initiated the idea of a contemporary art museum in Cornwall, to celebrate the work of Frost, Heron, Hepworth and the many other artists who had forged a new approach to art in Britain in the 1950’s. When Tate St. Ives opened in 1993, a large banner by Frost, painted on Newlyn sailcloth, was displayed in the entrance. Terry Frost died in Cornwall in 2003. Twelve years later, on the centenary of his birth, a retrospective exhibition of his work was held at Tate St. Ives.

In the 1956 Smeaton Pier photograph are Terry and Kath Frost, flanked by their sons Adrian and Anthony. To their left is the poet and budding architect David Lewis, who had come to Britain from South Africa (the girl beside Lewis has not been identified). After moving to St. Ives, Lewis became secretary of the Penwith Society and promoter of the town’s artists. Like Frost, Mitchell, Hilton, Dorfman and others, he worked for a time as an assistant to Barbara Hepworth. In 1949, Lewis married Wilhelmina Barnes-Graham. However, seven years later he departed Cornwall, to study architecture in Leeds and to work with Peter Stead on modernist housing. This led to a new career in the United States, where he taught at Carnegie-Mellon University in Pittsburgh and was a co-founder of Urban Design Associates (UDA). In 1985 Lewis was the catalyst for the retrospective exhibition St. Ives: 1939-64, at the Tate Gallery.

Other photographs on that same contact sheet include shots of terraced granite houses on Back Road, and a Land Rover parked on Teetotal Street, where David Lewis lived at No. 4. A narrow thoroughfare, Teetotal Street has changed little over the years, although now it is littered with green wheelie bins. In another photograph, Kath and the girl stand beside a clinker-built boat drawn up on the solid granite setts of the pier; today the boats are gone, their place taken by brightly-coloured plastic surf boards. However surfing has been popular in Cornwall for many years, and in the summer of 1955, the beaches were thronged with holiday-makers, many of them carrying small plywood surfboards.

Photograph by Adrian Flowers

Text: Peter Murray

Editor: Francesca Flowers

All images subject to copyright.

Adrian Flowers Archive ©

With thanks to Anthony Frost and Colleen O’Sullivan