Brian Duffy, photographer

1933 – 2010

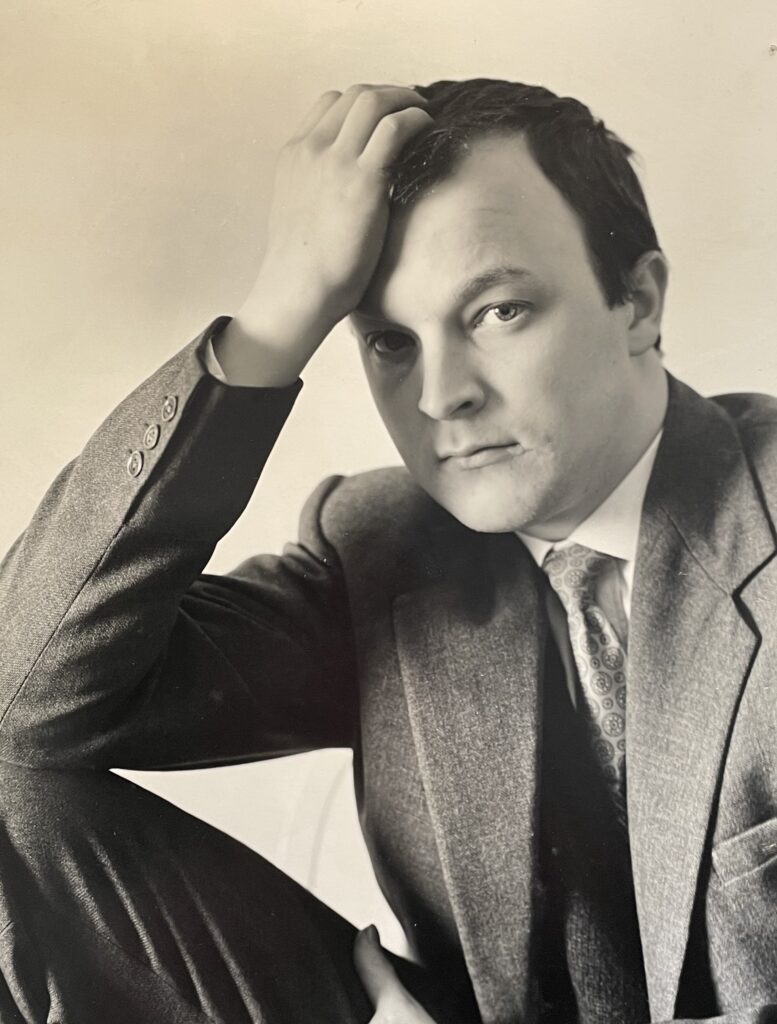

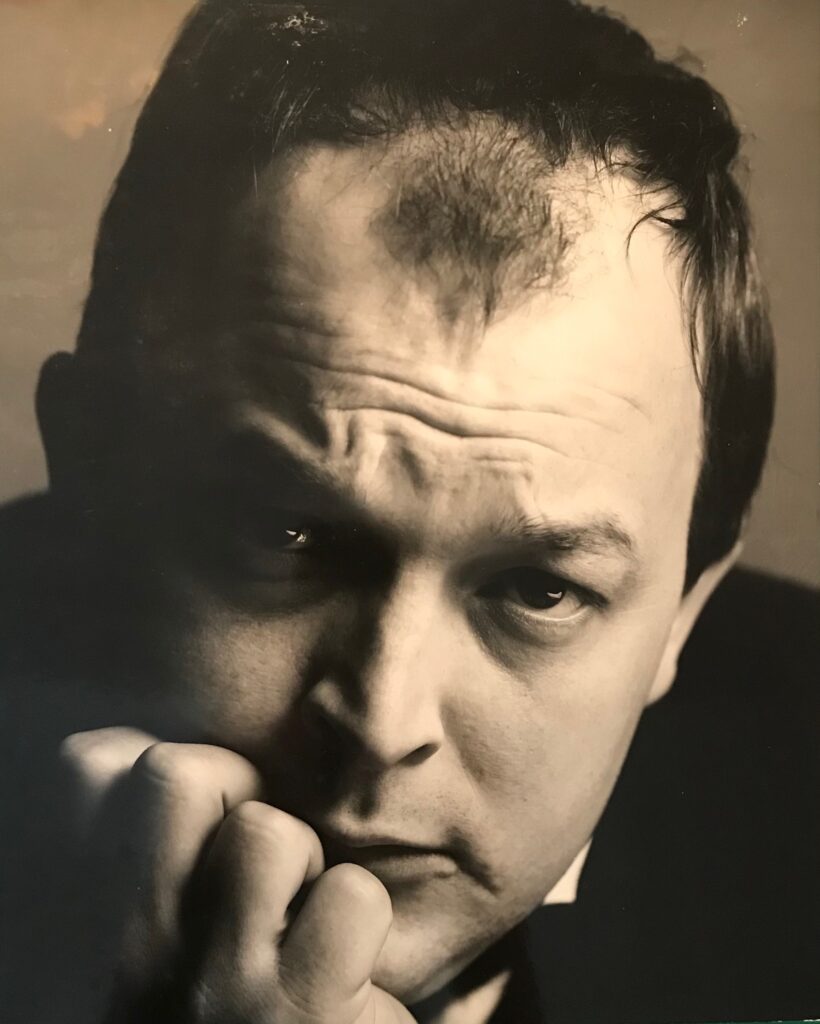

Directed by Linda Brusasco, the television documentary The Man Who Shot the Sixties recounts the life story of Brian Duffy, a portrait photographer famous for his gift of charming, enchanting—and occasionally antagonising—his sitters, but also, more importantly, for his ability to capture superb images on film. In his conversations with colleagues and clients, Duffy could be both funny and caustic, but he was a highly sensitive individual, with an intimate knowledge of the world of fashion and clothing. Famously argumentative, he often found himself in the company of the rich and famous; top models, actors and politicians, but was also on good terms with the London’s East End community, including the notorious Kray brothers. Duffy became one of the top photographers at Vogue, and was later an imaginative director of short films for rock bands, but in 1990 he packed it all in, to set up a furniture restoration workshop in Camden where he worked for the next twenty years. A star during the swinging sixties, along with Terence Donovan and David Bailey, by the turn of the twenty-first century Duffy had faded from public view. Broadcast by the BBC in 2010, The Man Who Shot the Sixties was a timely step in promoting a wider awareness of this remarkable photographer, who had died that same year.

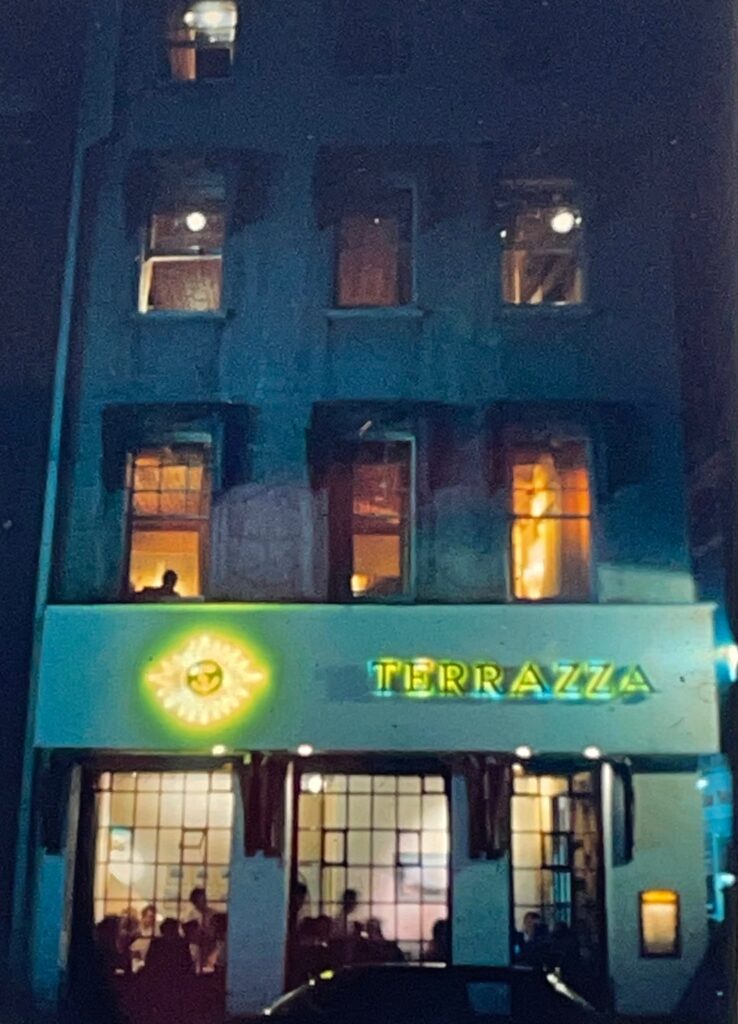

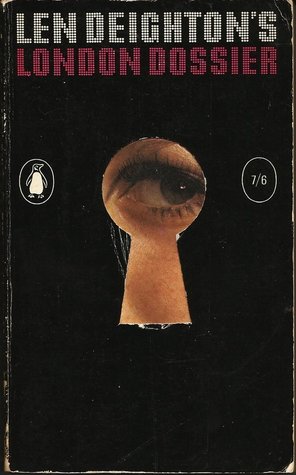

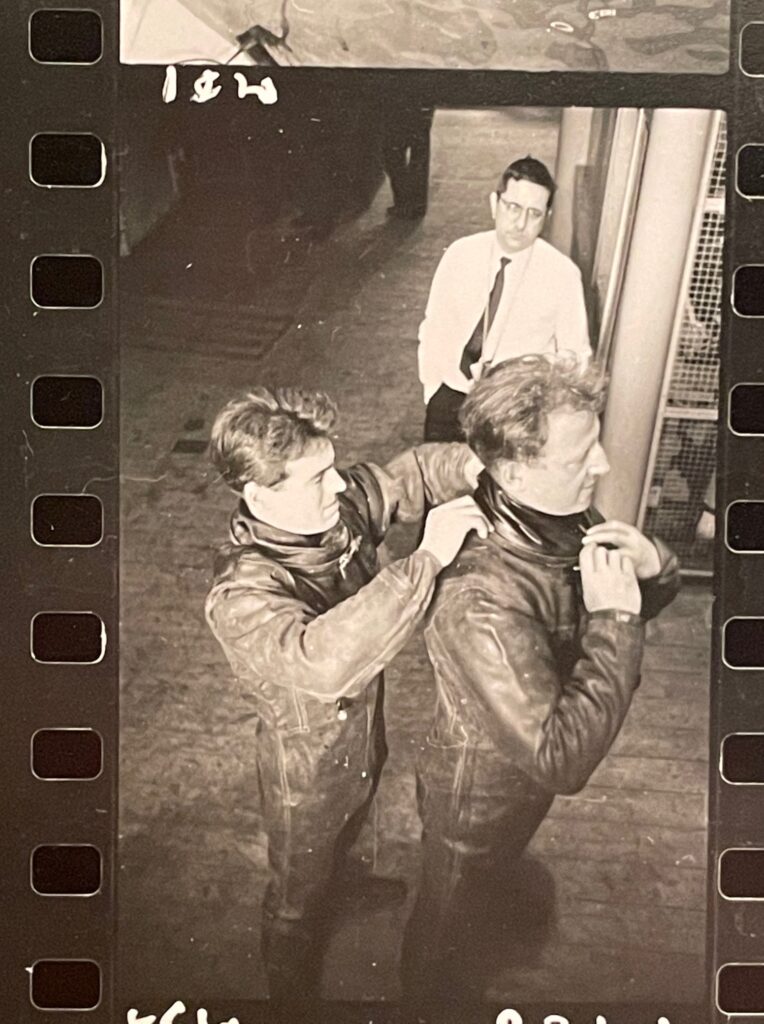

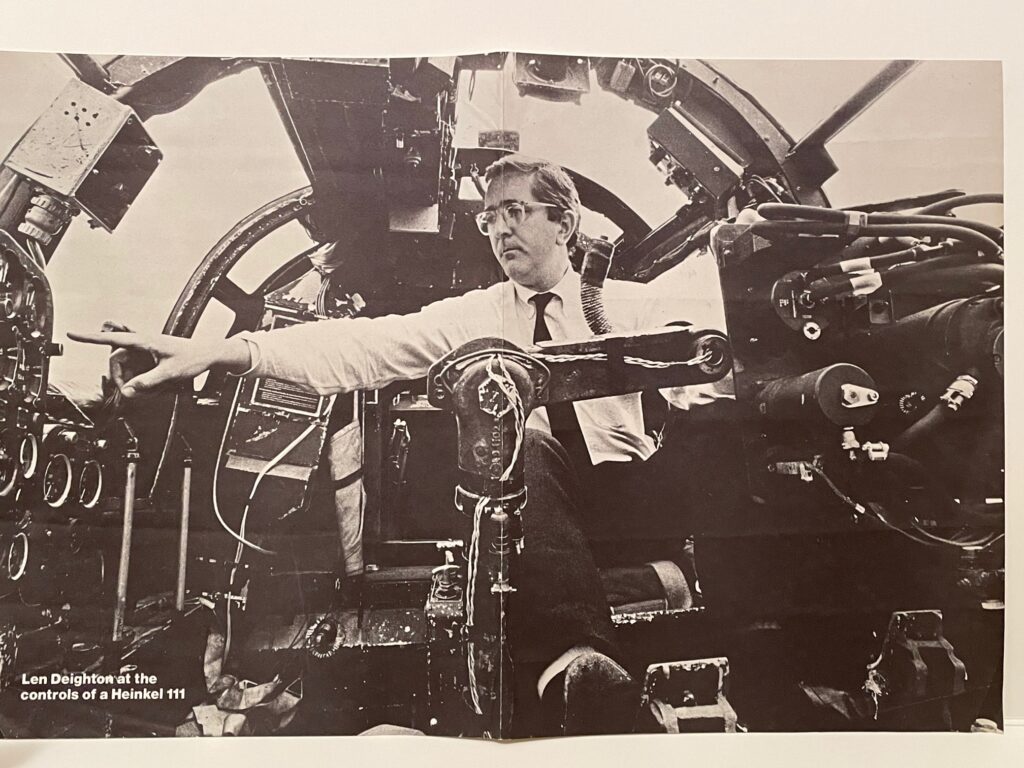

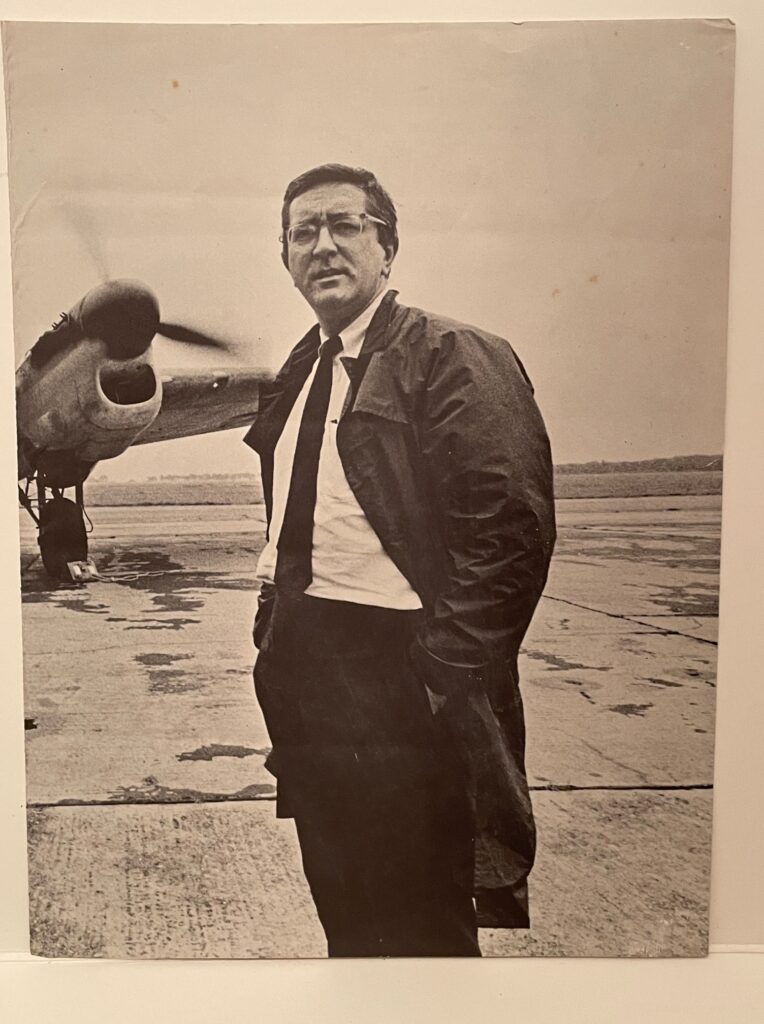

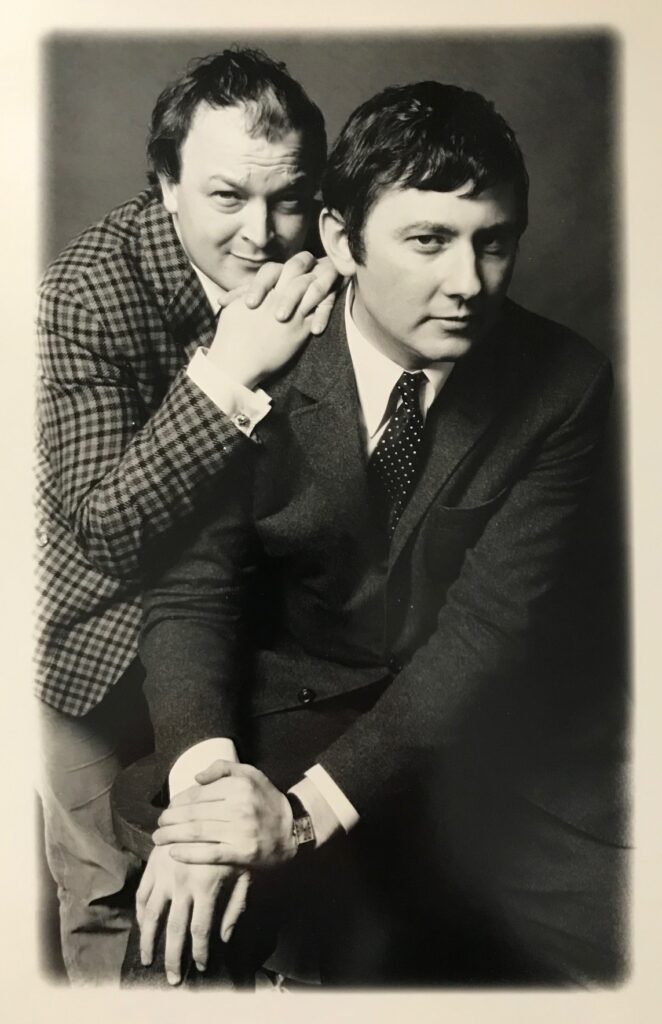

The Adrian Flowers archive includes several sets of photographs of Duffy. The earliest are individual portrait shots taken in January 1958, while the latest date from 1966, and were taken after a celebratory lunch at Alvaro’s restaurant on the King’s Road in Chelsea. In April of that year Duffy had photographed Alvaro Maccioni and his staff at the opening of the new restaurant, an enterprise which immediately rivalled the legendary Trattoria Terrazza in terms of its celebrity and film world clientele. After the lunch, on the spur of the moment, a group including Len Deighton, Duffy, Donovan, and Norman Brand, decided to call in to see Flowers at his studio on Tite Street. Ten years before, a young and inexperienced Duffy had been taken on as assistant photographer by Flowers. Norman Brand had worked for Vogue until 1962, when he joined Duffy at his studio in King Henry’s Road, Primrose Hill. Brand recalls the visit to Flowers: “I don’t know why but as we left it was decided that we would stroll down the King’s Rd and turn left into Tite Street where Adrian had his studio. After the usual chat someone said we should do a group portrait! I have always remembered this occasion and the photo being taken and always regretted never seeing the result but am thrilled to see it after all these years!” A series of photographs, formal and informal, were taken. In several of these, Duffy and Donovan pose together, laughing and joking.

photograph by Adrian Flowers at his studio in Tite Street, 1966

There is also a series of ‘family’ portraits, where everyone assembled good-humouredly in front of the camera. In these, Adrian stands to the right, cable release just visible in his hand. Behind him, wearing spectacles and smiling, is Brand. Deighton is at the back, wearing a white linen jacket, with Donovan to his right. Tousle-headed and with his characteristic impish smile, Duffy is kneeling at the front. He is wearing a tie, as indeed are all the men in the photograph. Donovan looks particularly formal, as if about to attend a funeral. The woman wearing the fashionable trouser suit has not been identified, nor the man in the foreground, leaning on his elbow. The photograph celebrates the culmination of Duffy’s career, when he was launching himself into the world of film production, after achieving fame as a stills photographer.

Born in Paddington, north London in 1933, to Irish parents, Duffy grew up in a world defined by conflict, and spent most of his childhood in a city regularly subjected to air raids. During one period of intense bombing he was temporarily evacuated, to the home of actors Roger Livesay and Ursula Jeans. However, through most of the war years he lived in London with his parents. His father, a cabinet-maker, was politically active and at one point had been imprisoned for involvement with the IRA. His mother was from Athlone, had an eye for stylish clothes, and was a devout Catholic. Escaping the confines of a household where religion and Republicanism were closely linked, Duffy and his friends enjoyed the freedom of the city—albeit a freedom tinged with fear—as they explored bomb sites and wrecked houses. Duffy’s parents never moved to the East End. His son Chris Duffy recalls: “my Mum’s parents lived in East Ham and I was brought up there until the age of five, so Duffy’s association with the East End was through my Mum’s side.” David Bailey, five years younger than Duffy, also grew up in this area. A rebellious teenager, often ending up in trouble, Duffy was fortunate to come of age at a time when the recent Butler Act had abolished school fees, opening secondary education to children from working class homes. He was also lucky in attending a progressive school in South Kensington run by ex-servicemen, the purpose of which was to introduce children to a wide range of culture, including opera, galleries and museums.

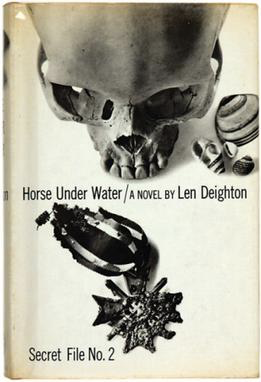

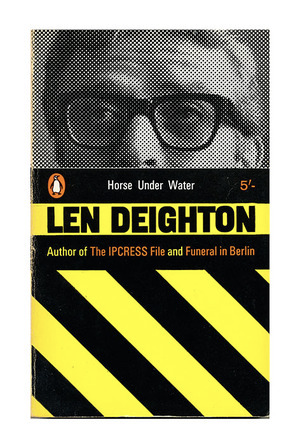

At the age of seventeen, Duffy enrolled in St. Martin’s School of Art, hoping to become a painter, but, intimidated by the skills and intellectual discussions of his fellow-students, switched to fashion design. At college he met Len Deighton; they formed a life-long friendship. After graduating, Duffy worked for Susan Small, and then for Princess Margaret’s dress designer, Victor Stiebel. Later he worked for Harper’s Bazaar, where the art director Gill Varney showed him how photography and fashion were closely intertwined. Deciding to take up photography, Duffy had a series of short-lived apprenticeships, and a spell at Artist Partners, before being taken on as an assistant in 1956 by Adrian Flowers. Although Flowers came from the same background as did many of the leading photographers of the day—John French had been in the Grenadier Guards, Cecil Beaton had been to Harrow and Cambridge, while Flowers himself attended Sherborne—he recognised and encouraged young talented photographers, irrespective of backgrounds or accents.

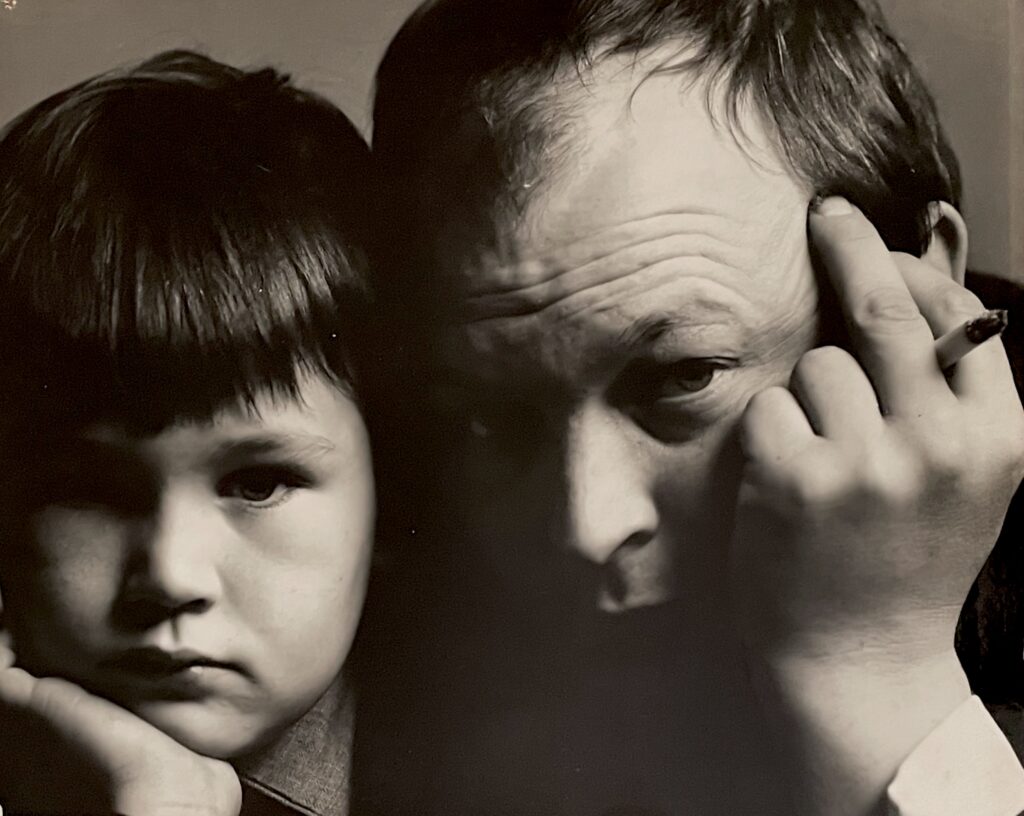

Photograph by Adrian Flowers, 1966

Terence Donovan also worked as an assistant in the Flowers studio. During this time Duffy received his first commission, from Ernestine Carter, fashion editor of The Sunday Times magazine. He was a star photographer for this publication for over twenty years, working closely with art director Michael Rand. In 1957 he was hired by Vogue, and grew to admire its editor Audrey Withers, another person willing to take a risk promoting young talent. Duffy loved France and, beginning in 1961, began to spend time in Paris, working for Elle magazine, where Peter Knapp was art director. For Elle he photographed Ina Balke and other models in Parisian street settings, as well as on the Cote d’Azur and Morocco.

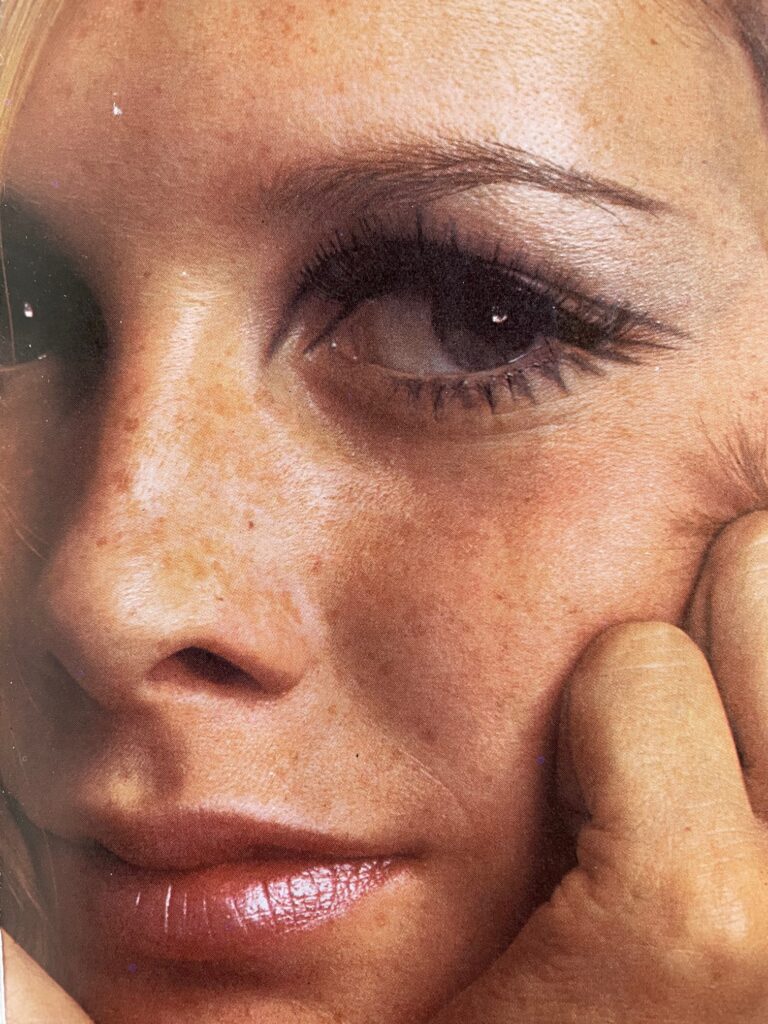

Independent, averse to being told what to do, using 35mm cameras and Rolliflexes, working at a fast pace, often in street settings, Duffy, Donovan and Bailey broke many of the conventional rules of photography and were variously referred to as ‘the black trinity’ or ‘the terrible three’. Duffy’s photographs were inventive, with dramatic compositions, often close-cropped. His models, their arms raised in angular poses, sometimes bring to mind the iconography of saints in ecstasy. He was also conscious of cinema, and his photograph of people running underneath cranes could easily be a still from Trauffaut’s 1962 Jules et Jim, while in 1964, his photograph of Celia Hammond, arms outstretched on a street in Florence, could equally be from Kalatozov’s film Soy Cuba, released that same year. This acute visual awareness informs many of Duffy’s images; a model turning and reaching her hand backwards in an open limousine, taken for Town magazine in 1965, recalls the terrified actions of Jackie Kennedy two years earlier in Dallas. Duffy worked for Vogue for six years, photographing Kellie Wilson, Francoise Rubartelli, Jean Shrimpton, Jennifer Hocking, Joy Weston and other top models. Many of the best photographs of Joanna Lumley were taken by him. For Queen magazine he photographed Nicole Da La Marge, Paulene Stone, and Jill Kennington. He also often worked with model Marie-Lise Gres, and in 1962 photographed her at Castletown House in Co. Kildare, a Palladian house being restored by Desmond and Mariga Guinness and the Irish Georgian Society. Duffy also worked for Esquire, the Observer, and The Telegraph, becoming well-known for his portraits. His sitters ranged from politicians to actors, including Harold Wilson, Michael Caine, Ursula Andress, Brigitte Bardot, Nina Simone and Sammy Davis Jnr. At Nova Molly Parkin was another perceptive art director who recognised his talent. For one provocative article “How to Undress for your Husband” the model Amanda Lear posed in states of semi-nudity. Lear had also studied at St. Martin’s and had been a long-time muse of Salvador Dali. Her true gender identity was often the subject of gossip, and she is said to be the inspiration for the character Patsy in Absolutely Fabulous.

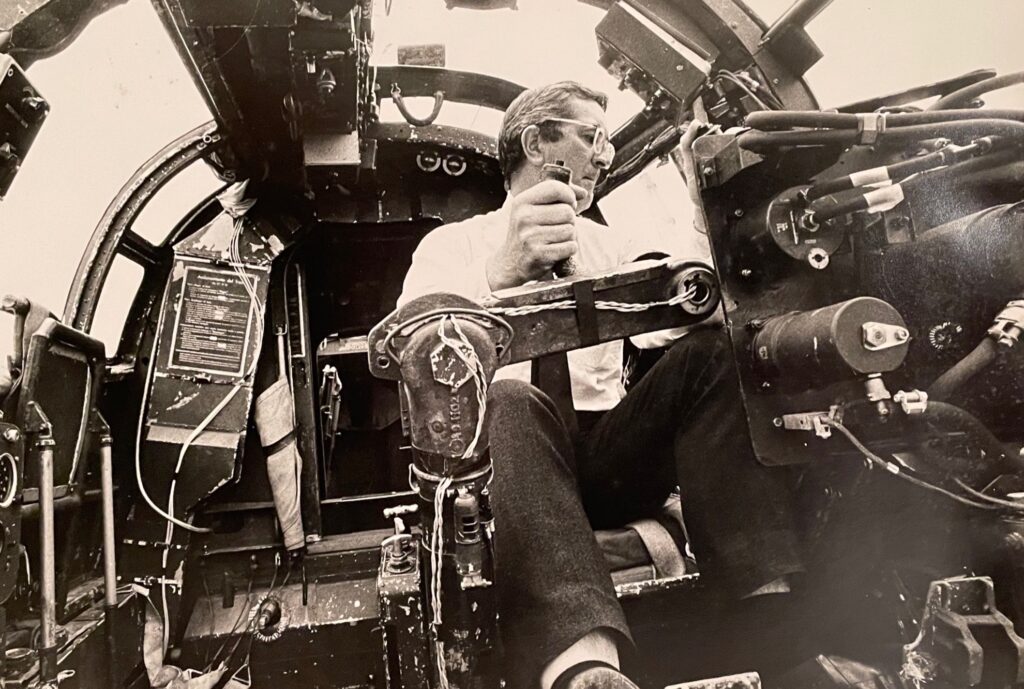

In 1966, Duffy was at the peak of his career, when Peggy Roche moved from Elle to become fashion editor of London Life magazine, where David Puttnam, himself the son of a photographer, was managing editor. Duffy took several of the cover photographs for this influential but short-lived magazine. Although the photographs used in Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-Up, made that same year, were by Don McCullin, the film was largely based on the work and lifestyles of Duffy, Donovan and Bailey. By the late 1960’s, with Puttnam now his agent, Duffy was moving away from stills photography, and becoming involved with Len Deighton in a film company. The company headquarters were at the bottom of Park Lane, in Piccadilly, the grand offices featuring a partner’s desk, made by Derek Gamble, in the shape of an propeller. Their productions included the 1968 Only When I Larf, and the following year Oh What a Lovely War, films directed by Basil Deardon and Richard Attenborough respectively. The team that travelled to Beirut in 1967 for Only When I Larf included Duffy, Deighton, Brand and Deardon. Having acquired the rights to the musical play Oh What a Lovely War, by Joan Littlewood, Duffy put together a team to film the production on Brighton Pier. However his hopes of directing the film were quashed by trade union regulations so instead he became the producer. Obsessed with World War I, Duffy had an extensive library of books on the topic. He also shot Lions Led by Donkeys a documentary made for Channel 4 about the battlefield of the Somme. David Puttnam’s 1987 film Hope and Glory is a moving depiction of the wartime London in which Duffy had grown up, and which had shaped his attitude to life.

Ever restless, Duffy moved on and began to specialise in more technically-sophisticated photography. In addition to working for the legendary Pirelli calendar, where he used Monaco as the location for his first portfolio in 1965, he photographed the musician David Bowie over a period of several years. The resulting images came to define Bowie’s stage persona, with four being used on album covers, including the 1973 Aladdin Sane. During these years, Duffy also focused on advertising campaigns for CDP, (where Puttnam had also worked), notably those for Smirnoff, Aquascutum, and for cigarette brands Silk Cut and Benson and Hedges, where his surreal visual imagination came into full play. For Aalders Marchant Weinreich he photographed Mary Quant products. He also worked for Biba. However, having conducted the equivalent of a guerrilla war within the elitist world of advertising for almost three decades, in 1990 Duffy retired, to concentrate on the craft of furniture restoration.

In 2010, two years after his son Chris has founded the Archive that bears his name, Duffy died of pulmonary disease. Unrepentant to the end, he observed “keeping your tongue up the society that pays you is an art of which I was void.” At his funeral the eulogy was delivered by David Puttnam, who observed that ‘the world needs more Duffys’, describing him as a ‘supremely talented and esoteric man . . a man who thrived on risks and challenges, who lived to create.’ Although he had destroyed many of his negatives in the late 1970’s, enough have survived to form a substantial collection. Over the following years, the Duffy Archive has thrived, becoming an invaluable resource of images that define the visual culture of the late twentieth century, and maintaining an online portal for the thirty or so galleries that represent Duffy’s work. Beginning in 2009 at the Chris Beetles Gallery in Mayfair, exhibitions of his photographs have been held around the world. The only showing of his work in Ireland, where both his parents were born and where he was conceived, took place in 2017, at the ebow gallery in Castle Street, Dublin.

Text: Peter Murray

Editor: Francesca Flowers

All images subject to copyright.

Adrian Flowers Archive ©

With thanks to www.duffyarchive.com