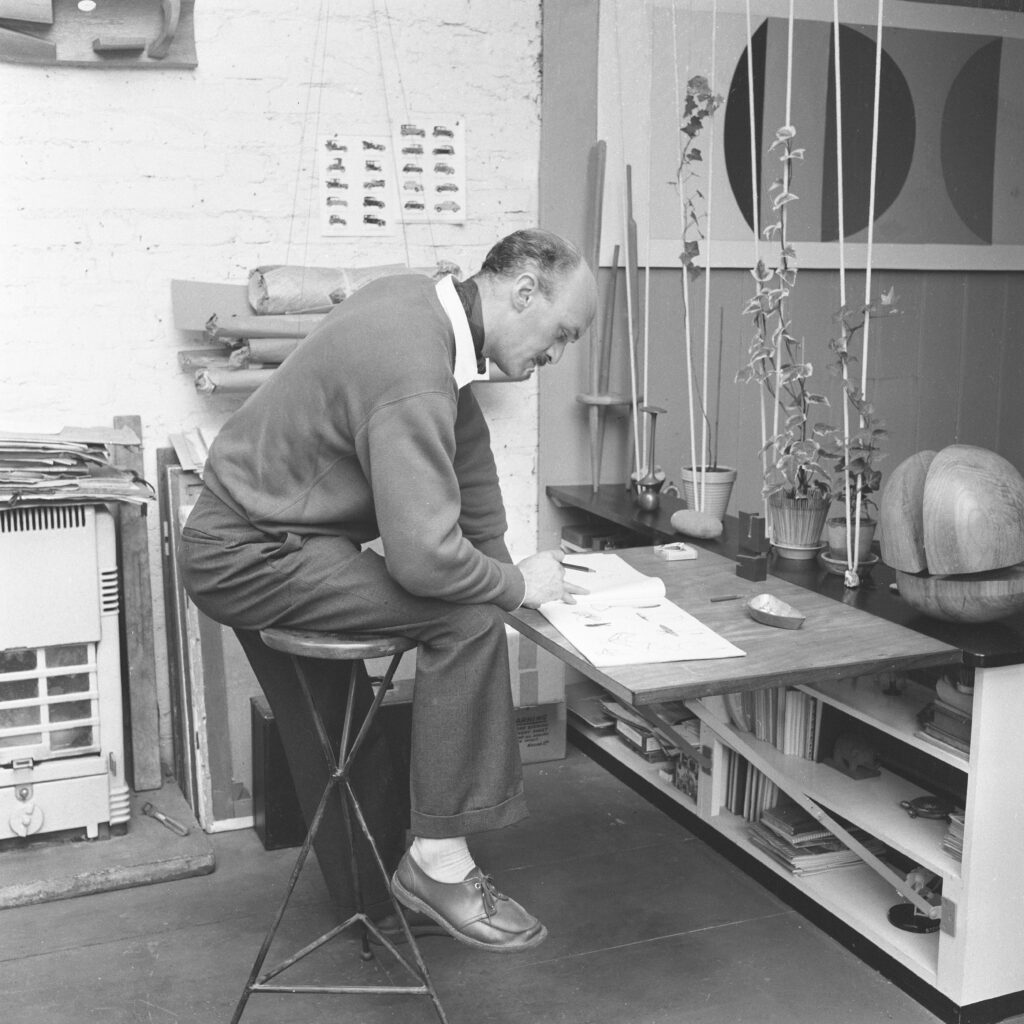

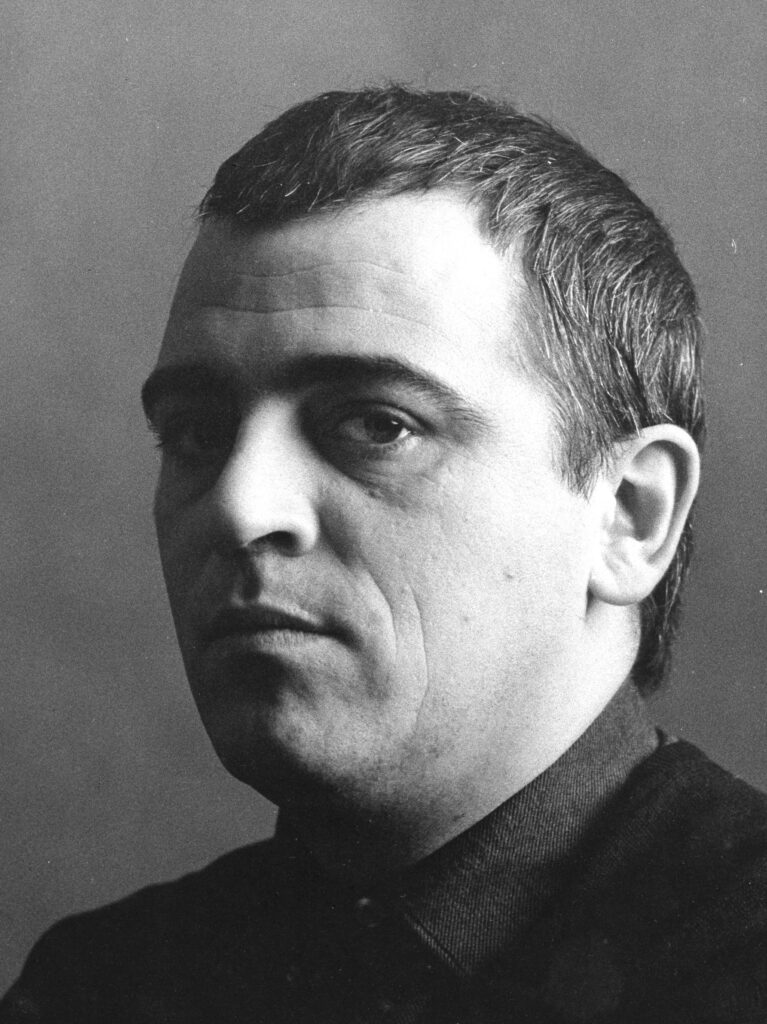

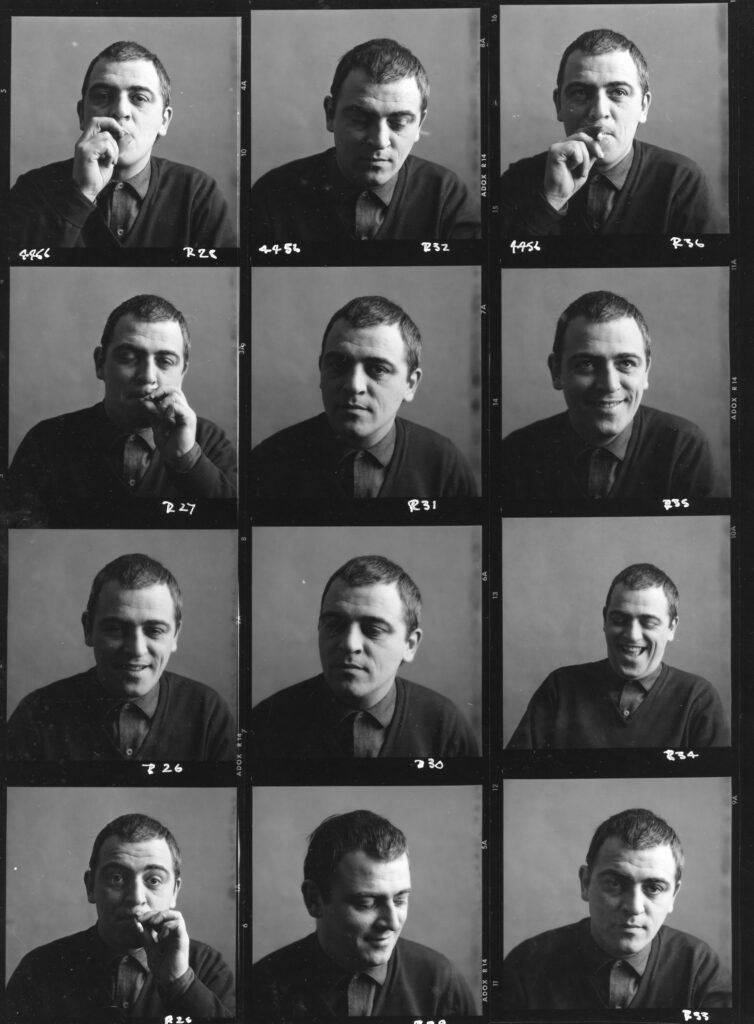

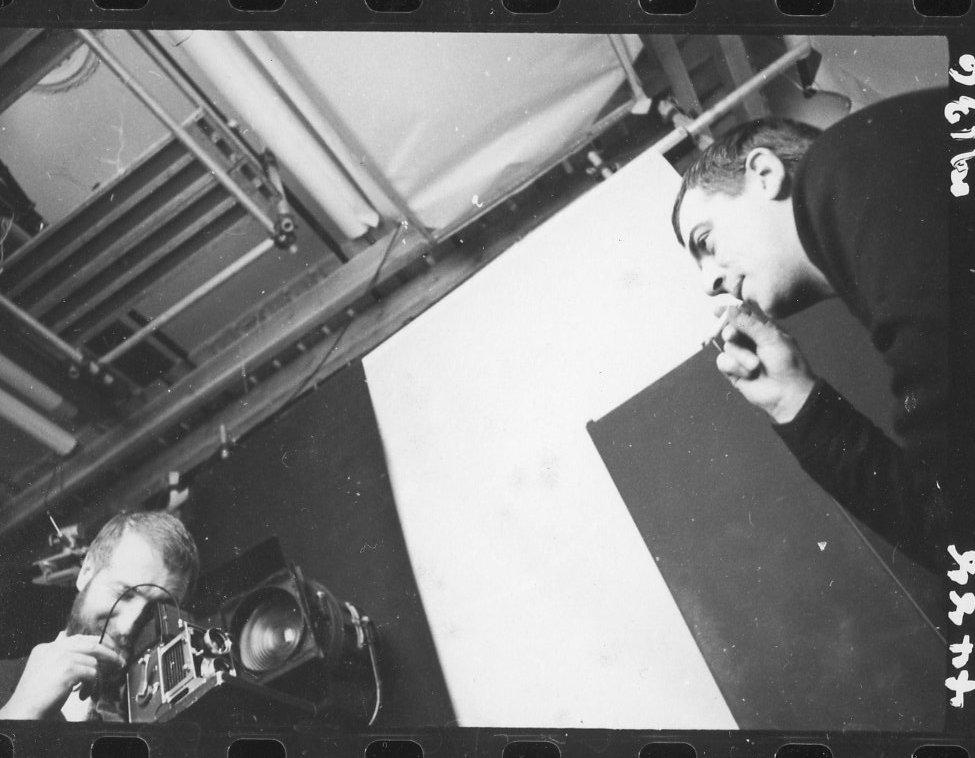

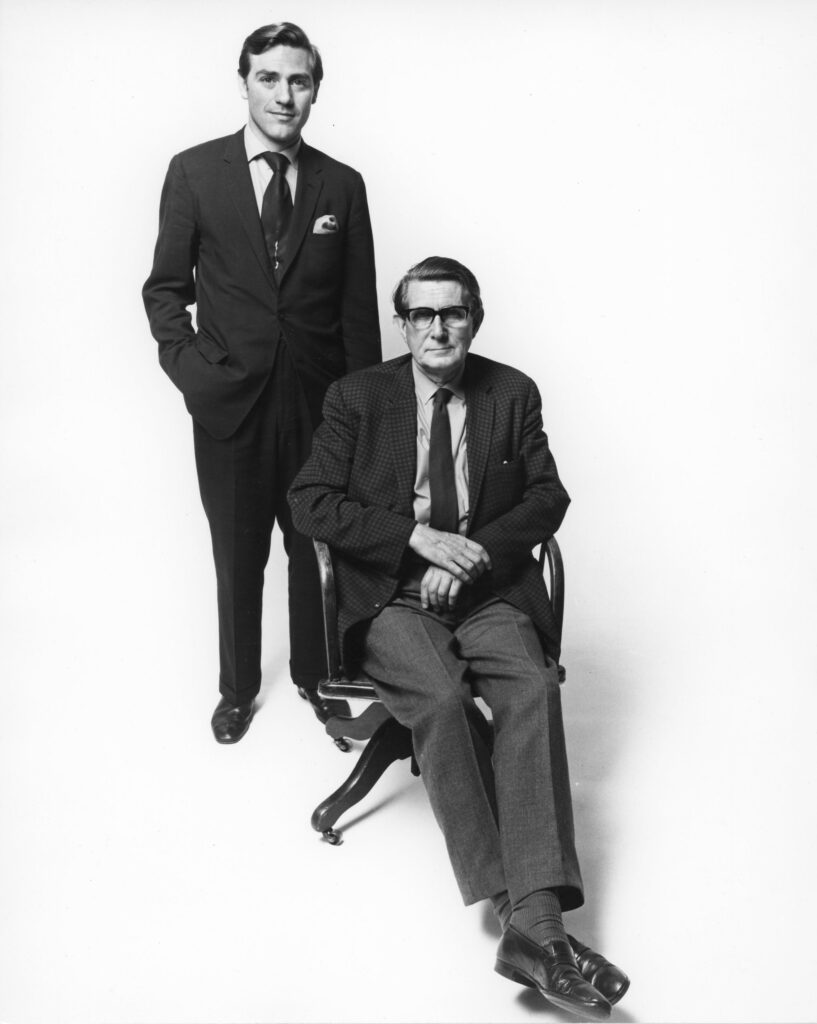

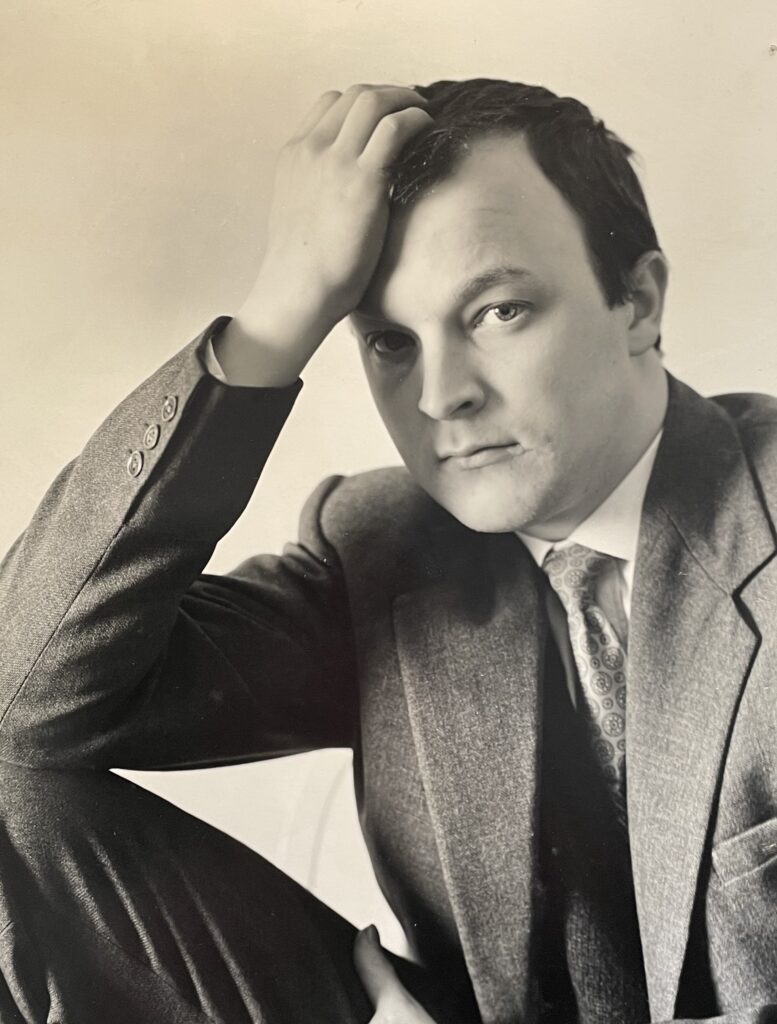

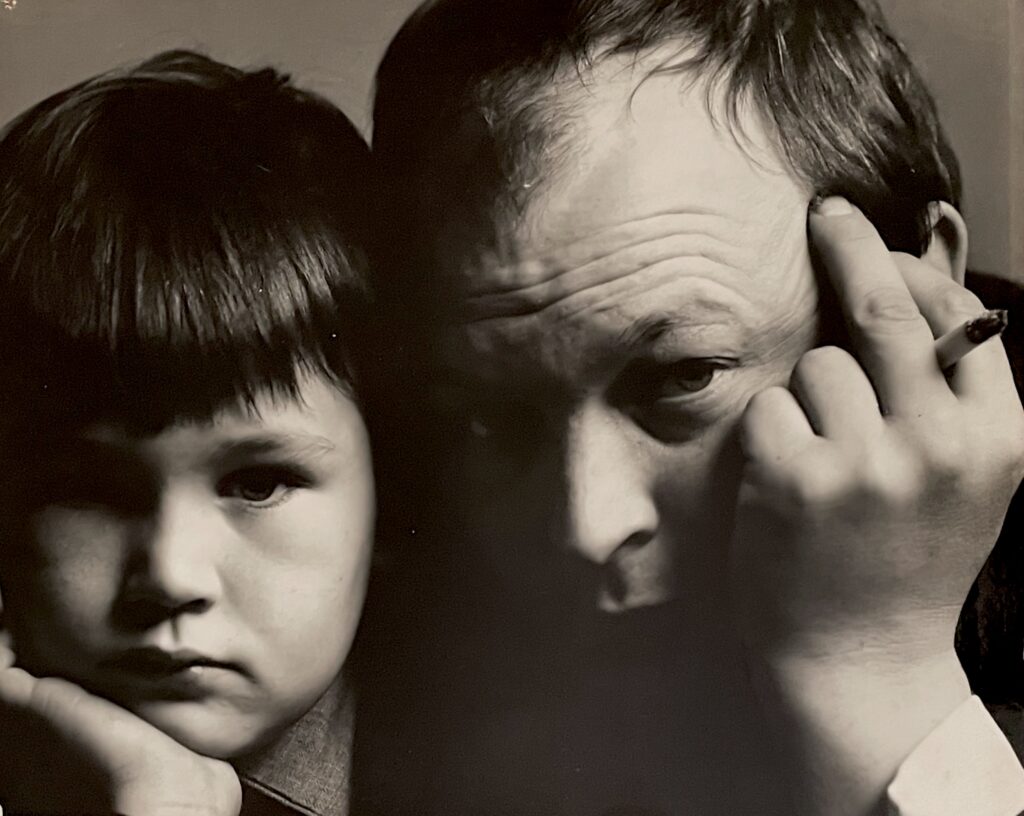

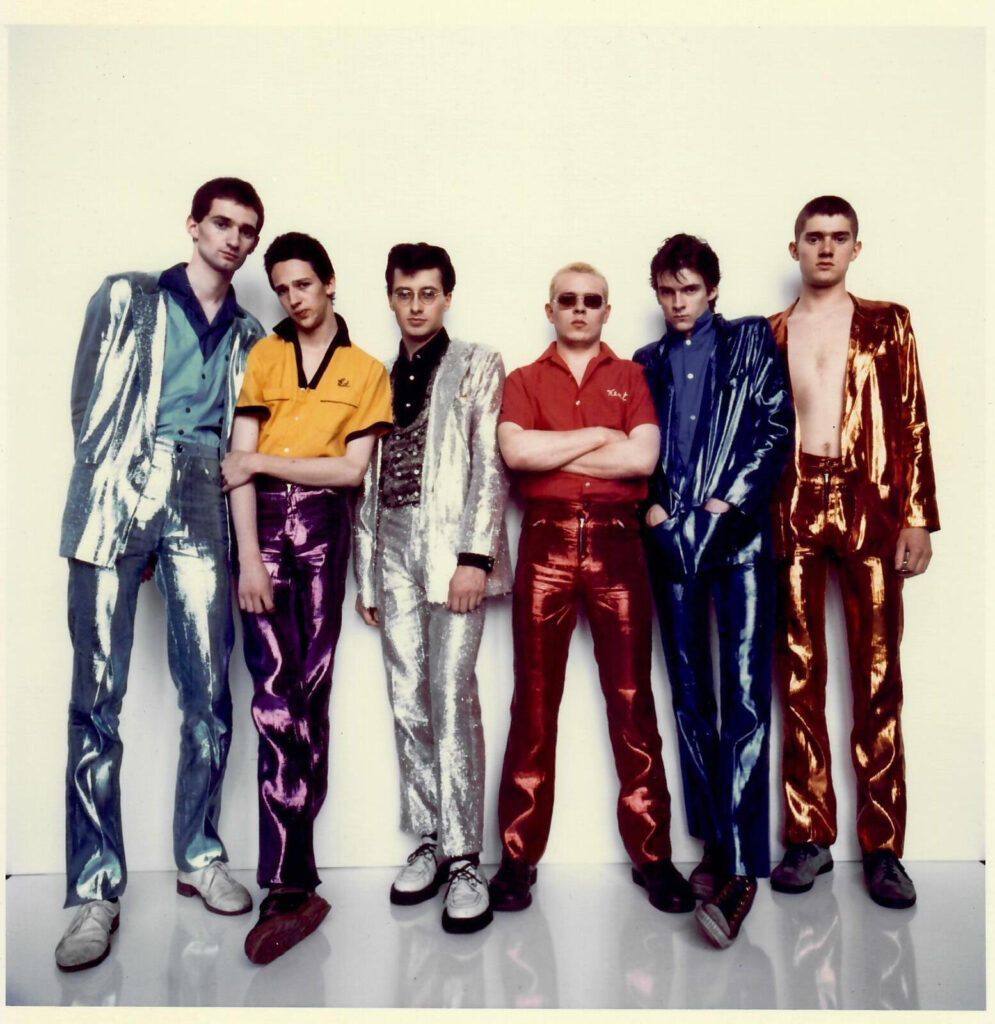

Photograph by Adrian Flowers at his studio in Tite Street.

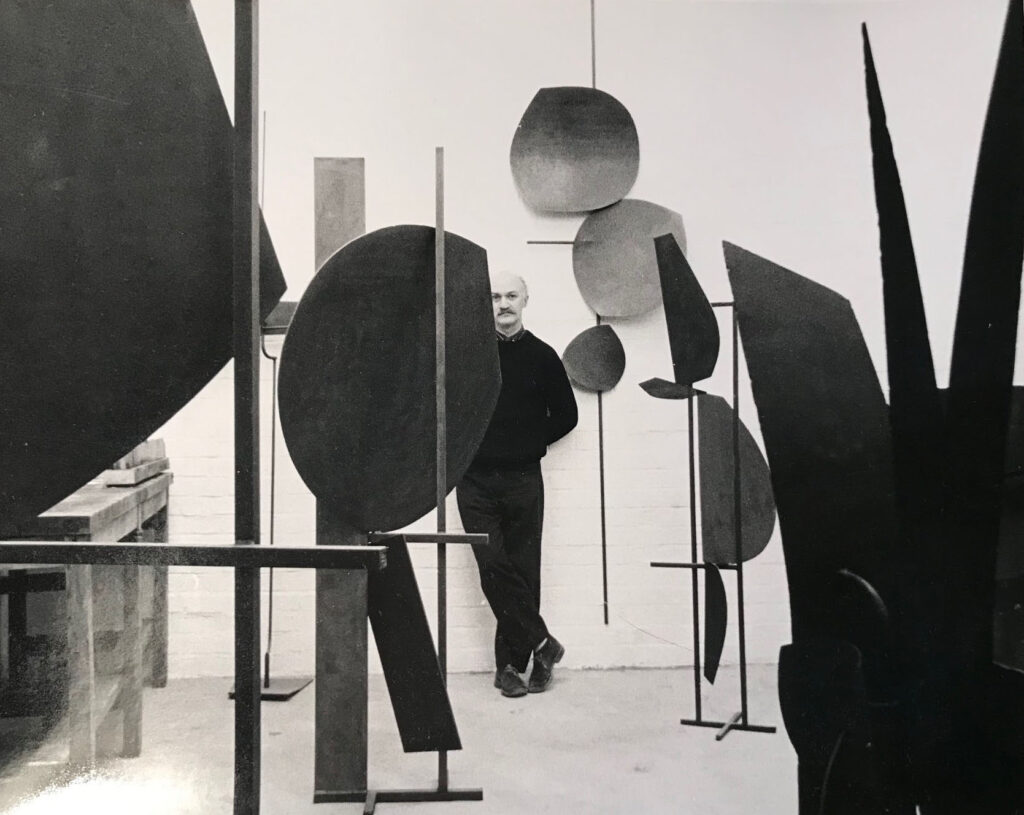

l-r: Matt Flowers, Reid Savage, Justin Ward, Clive Kirby, Greg Mason, Dan Flowers.

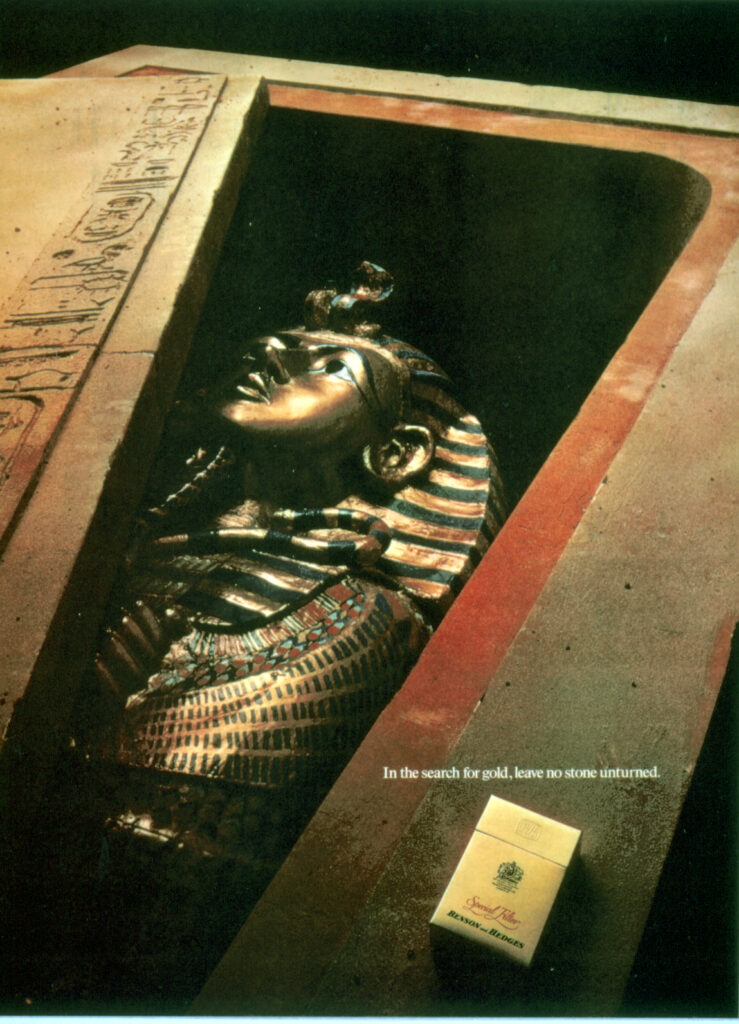

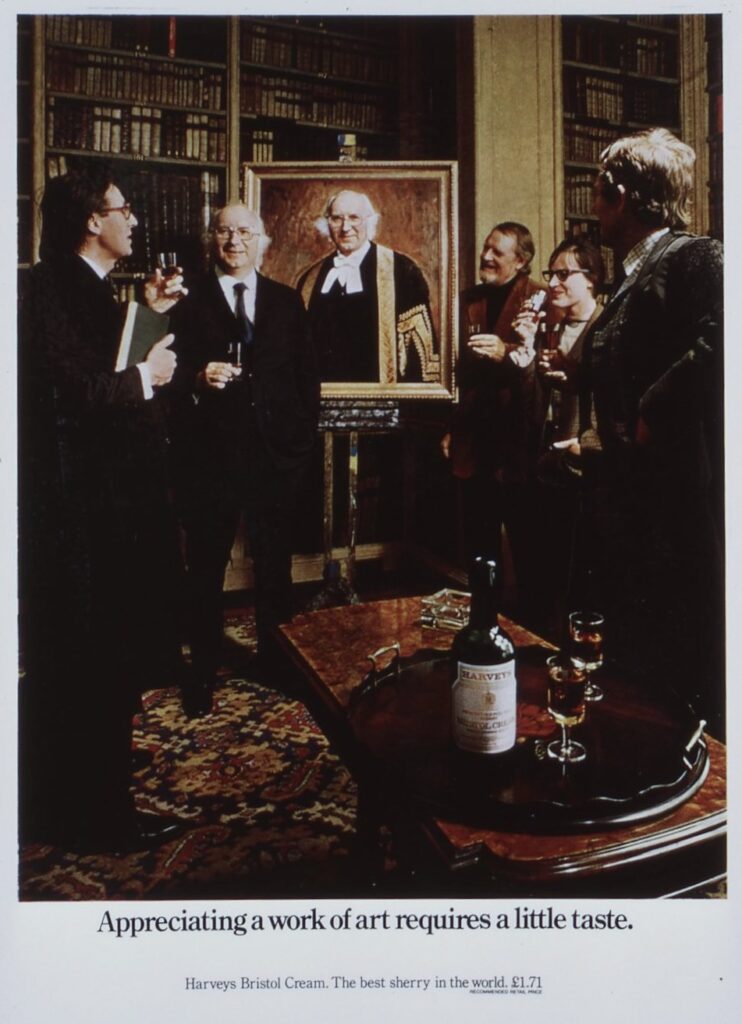

Founded in Kentish Town in 1975, Sore Throat was one of the most ambitious bands to emerge in London during the heyday of punk and new wave music. Active between 1976 and 1981, the band played over four hundred gigs, as well as releasing seven singles and one album, Sooner than you Think. Their singles included the 1978 I Dunno, released on Hubcap Records, the cover featuring a witty banana design by artist Patrick Hughes, with the track Complex on the double A side. Another single, Zombie Rock, appeared that same year, under the Albion label: “Things used to be so peaceful in the graveyard/Things were pretty dead of a night/The closest we would come to having any fun/was when the gravedigger died of fright.” This single also featured the rock-n-roll I Don’t Wanna go Home. The band performed Zombie Rock on the ITV television programme Revolver, compered by Peter Cook. The accompanying film, featuring ghouls digging their way out of graves, had in fact been the inspiration for the song. The single Kam-i-kaz-e Kid came out the following year, the cover featuring Robert Wiles’ photograph of Evelyn McHale, a young woman who jumped from the Empire State Building in 1947, landing on the roof of a car. With Crackdown on the B side, the single’s release was accompanied by full-page ads in New Musical Express. Not long after, 7th Heaven came out on the Hurricane label, with Off the Hook on the B side, while Flak Jacket, on the Fast Buck label, appeared in 1980. Diggin a Dream, produced by Laurie Latham, came out that same year, paired with Stocker Stomp. A final single, Bank Raid, with Seven Weeks on the B side, went on sale in 1981, on the Sea Food label.

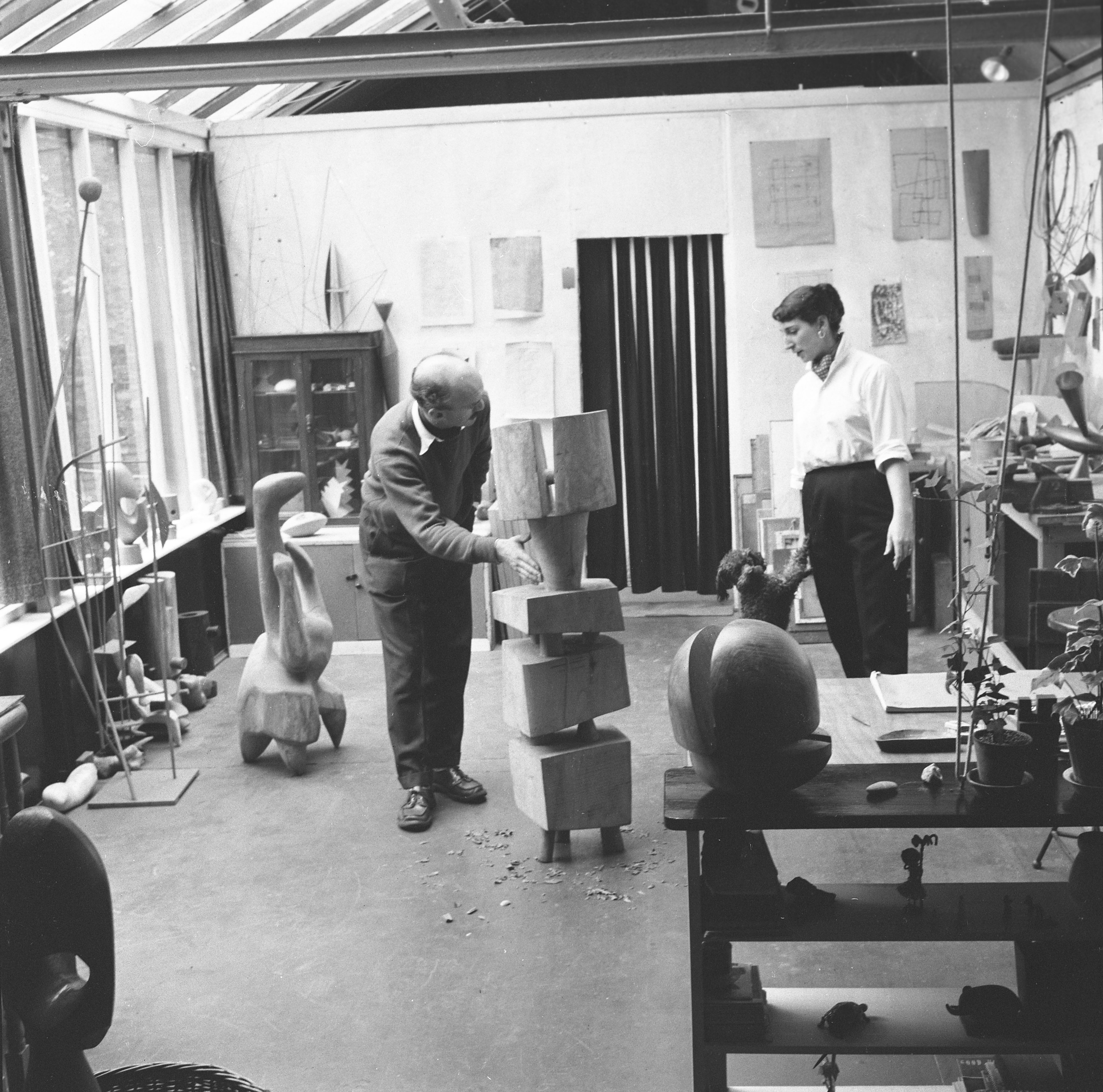

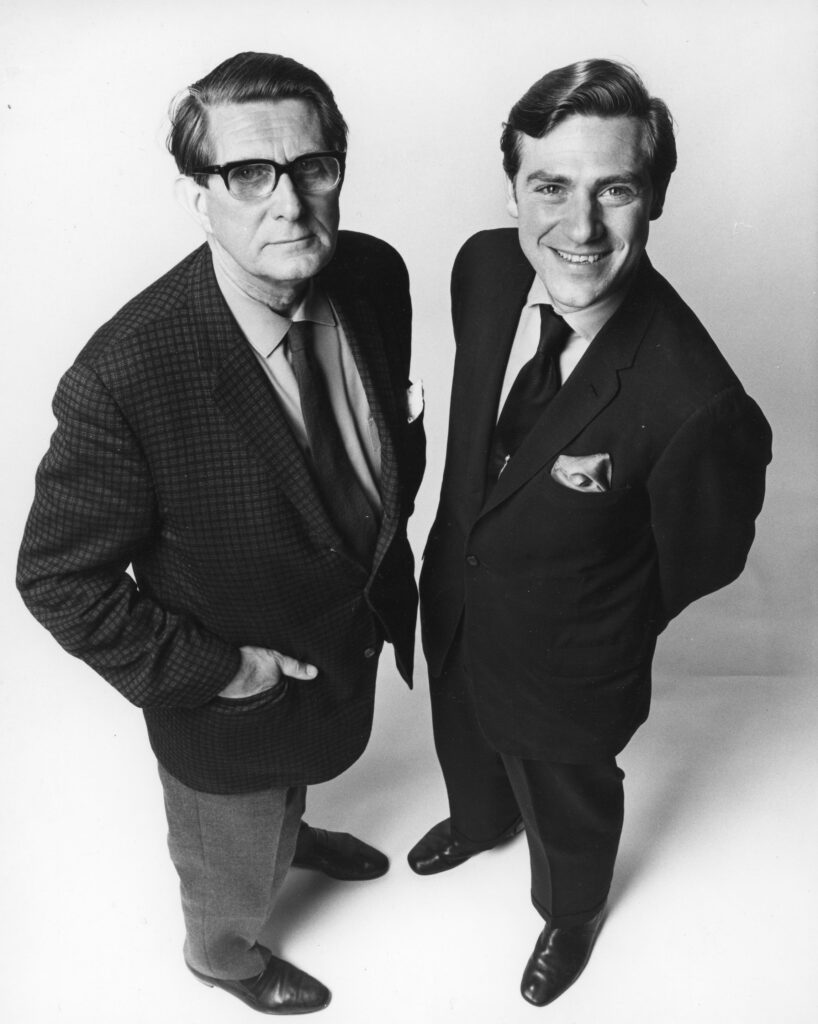

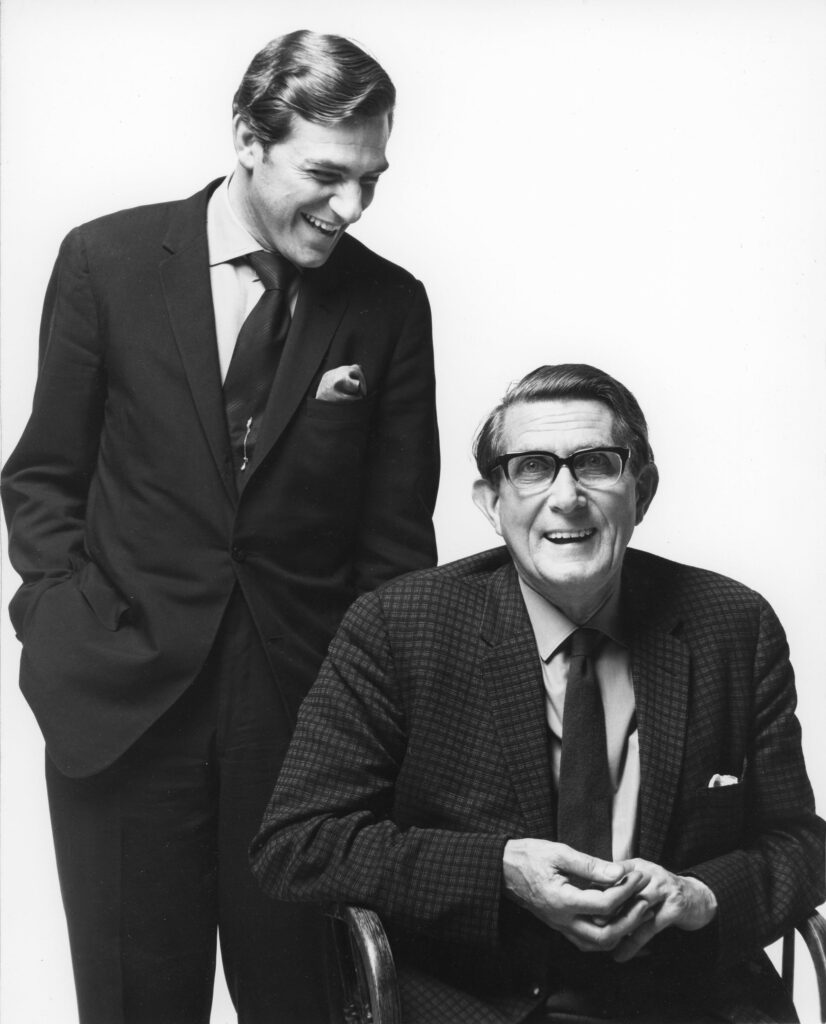

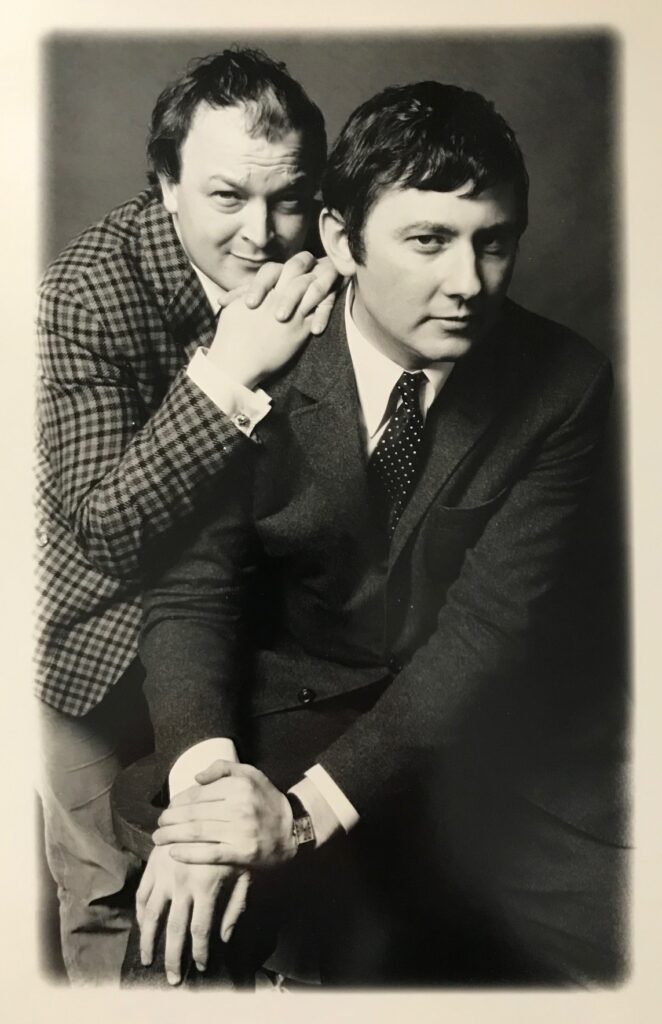

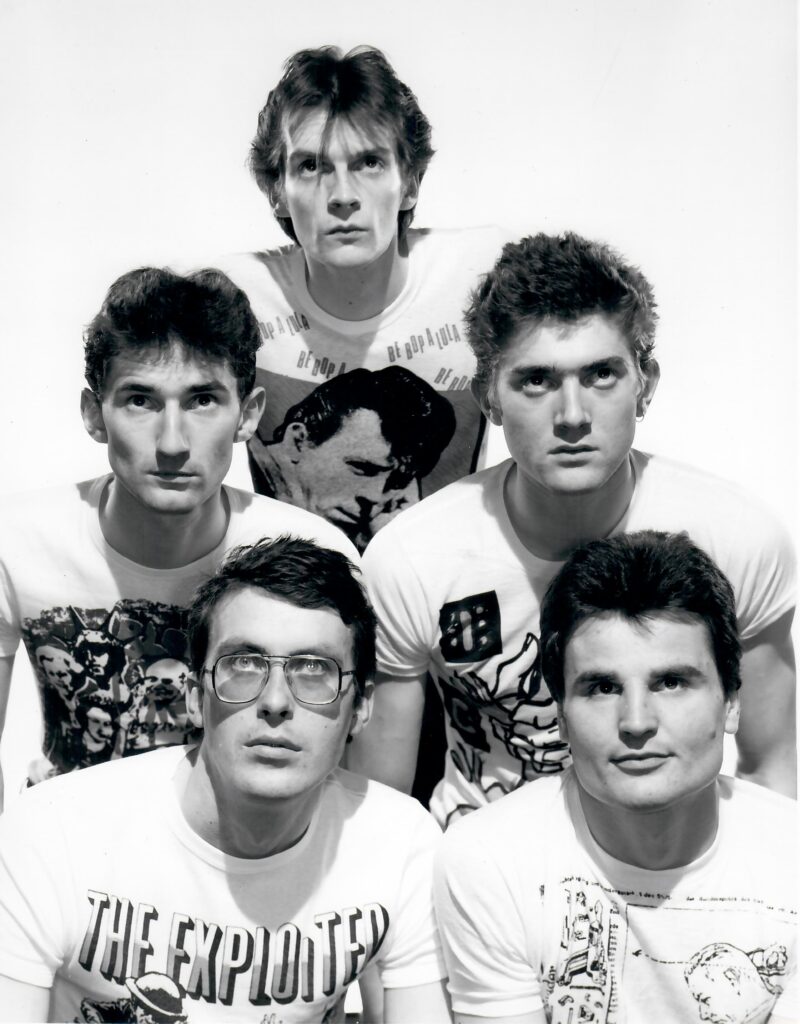

Matthew Flowers, Justin Ward, Dan Flowers

photographed by Adrian Flowers at his studio in Tite Street

Two of Adrian Flowers’ teenage sons were prominent in Sore Throat; Matthew on keyboards, and Dan on bass guitar. Sore Throat had evolved from earlier ensembles that Matt and Dan—along with school friend Ollie Marland—had set up at their school, William Ellis, in the early 1970’s. These were variously named The Moggers, The Blades, and The New Blades. Guitarist Reid Savage, Dan Flowers and saxophonist Greg Mason met at this progressive school in Highgate, where Marland formed a band called Landslide. With another Elysian, Clive Kirby, on drums, Landslide played at the Windsor festival in 1974. Marland later went on to work with Dave Stewart of the Eurythmics and eventually with Tina Turner and Cher, while Kirby was to join the up-and-coming Sore Throat. An early gig, under the name Jam, took place at St. Anthony’s School in Hampstead, in October 1974. More name changes followed, including Juice, before the band members settled on Sore Throat (not to be confused with a later grindcore band of that name in the late 1980’s). Over the years, musicians came and went, including singer/songwriter Justin Ward, Savage and Mason, the latter playing later on with Adam and the Ants. Mark Burton was the drummer, although he left early in 1976, with Robin Knapp taking over on drums.

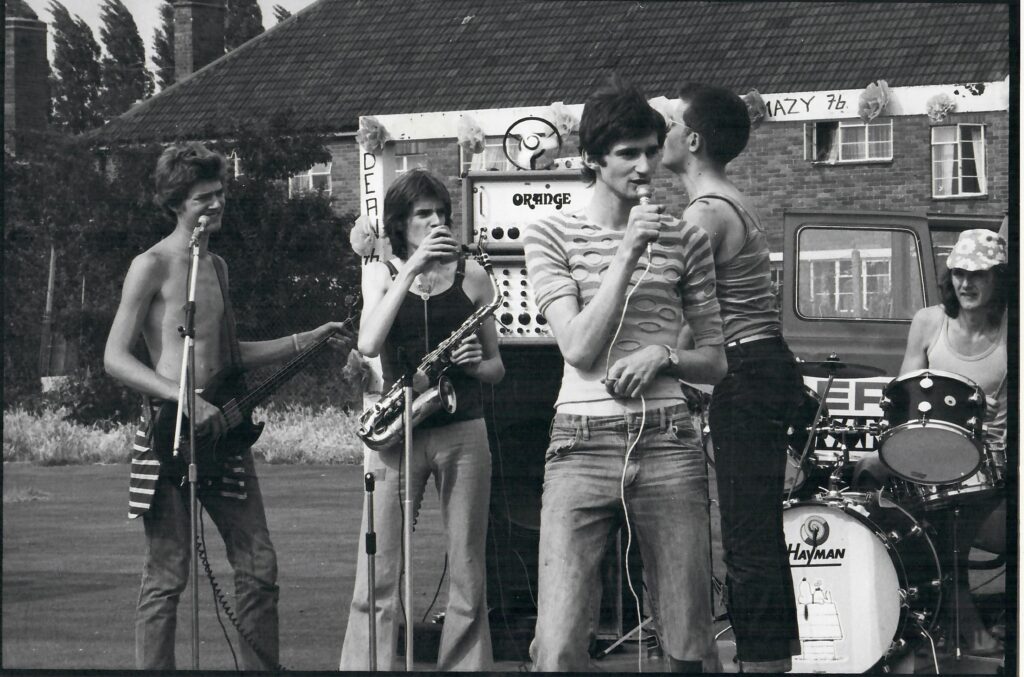

On February 27th 1976, Sore Throat played at Hampstead Town Hall on Haverstock Hill, supported by Razor Backs. Included in the set were the numbers Washout Stomp, Sunshine Blues and Puddles of Perfume. On July 3rd, at the invitation of John Pasmore (son of artist Victor Pasmore) they featured at an open air gig at Blackheath, and from August onwards began a series of regular Monday nights at the “Pindar of Wakefield” (now The Water Rats) at King’s Cross, the venue where Bob Dylan had played his first English gig. This residency continued through to November 1977. In May of that year, the band invited The Slits on stage at the Pindar for one of their first performances. Several gigs at the Pindar were photographed live by Adrian Flowers, who also photographed the band members at the Blackheath concert, and at his studio in Tite Street.

Tours throughout the UK followed, including a night at the Marquee Club, where, in addition to the Flowers brothers, the line-up included Ward, Mason, Savage, with Knapp (aka Knockerapp) on drums. On June 3rd 1978, writing in the New Musical Express, Neil Peter reviewed a gig at the Nashville Room :

Sore Throat’s music completely defies categorisation; it’s a weird synthesis of just about everything from ’50s rock ’n’ roll to jazz and more besides, rounded off with a very English eccentricity. They’re as diverting visually as they are musically, too. Ward is the star of the show, either the subject of violent convulsions or performing minor acrobatics throughout the set, but barely less striking is Matt Flowers, who stands well over six feet and occasionally leaves his keyboards to do some absurd dances or strangle Reid Savage, who doesn’t move too much but performs some comic, quasi-Robin Trowers facial contortions, while the monolithic Dan Flowers does Boris Karloff impersonations in the corner.

The band also performed regularly at the Stapleton in Stroud Green, and in 1978 supported Deaf School on a tour of eighteen venues. In turn, Sore Throat was supported by other up-and-coming bands including Adam & the Ants, Bad Manners and The Members. In 1978, supported by the talented but short-lived Blazer Blazer, Sore Throat played at the Music Machine (now Koko) on Camden High Street; other bands playing there at the time included The Dickies and The Clash. On 2nd April that year, writing in the German magazine Sounds, André Klasenberg gave a vivid account of a Sore Throat gig in Camden Town:

Clichés fail me – unknowns or not, Sore Throat provided some of the best live music I’ve heard this year at the infamous Music Machine last Tuesday night. Their hour long set was like all gigs should be but usually aren’t, an hour-long dazzling display of instrumental mastery, superb songs with lyrics that linger, backed up by amazing visuals to rival those of Split Enz and Deaf School (of course, they backed them on their last tour). This sextet from sunny Camden Town clearly owe a lot to bands like that, but they’re totally and uncompromisingly original in the way they do things. . . Manic jerky movements abound when they’re on stage, but so well arranged that you know they practise a hell of a lot. They’re sartorially smooth in dyed waiters’ jackets, with the cropped hair that seems de rigeur nowadays. Musical style changes with each song, one minute they’re Buddy Holly and the Crickets, the next Kilburn and the High Roads.

Sublime solos come thick and fast from sax, guitar, keyboard, you name it, and the vocal harmonising wouldn’t disgrace a Jan and Dean disc. Mr. Savage comes out with jangly block chords, so clear and piercing as to put Television’s Tom Verlaine to shame. Justin’s voice is ideally suited to the songs, all originals of course, with the exception of the encore ‘Shakin’ All Over’, which it later turned out was a first time for them; you’d never have known.

Matt Flowers is a 6ft 6ins vision of synchronised epilepsy – besides being imaginative and aggressive on keyboards he’d make a great singer if he didn’t keep falling off the stage. Controlled lunacy is clearly the name of the game. Every entertaining stage move you’ve ever seen, from the Shadows’ feet together swing to statuesque left/right turns to Family’s Roger Chapman spider on speed, appears sooner or later.

The following year, Sore Throat invited two relatively unknown bands, The Snivelling Shits and another Camden band, Morris and the Minors, to support them at The Music Machine. The night of the gig, February 22nd 1979, Morris and the Minors changed their name to Madness.

By that time, Robin Knapp had left, to be replaced by Clive Kirby, the drummer from Landslide. Soon afterwards, Sore Throat signed with Hurricane Records, then run by Phil Presky and distributed by Warner. Pete Shelley of The Buzzcocks witnessed the signing of the contract. Produced by Neil Harrison, the band’s first, and only album, Sooner than you Think, came out soon after. Recorded at Abbey Road Studios, it was released on the Hurricane label, with a cover designed by artist duo Boyd & Evans. The tracks included Wonder Drug, 7th Heaven, Flak Jacket, Routine Patrol, British Subject, Mr Right, Off the Hook, Crackdown and Sooner than you Think. Promoting the album, an ‘Eiffel Tour’ took in Manchester University, High Wycombe Town Hall, Burton-on-Trent’s 76 Club, East Redford, Leeds Fan Club and “The Underworld” in Birmingham. With Graeme Cooper as road manager, Sore Throat also toured in Europe, taking in Ireland, Holland, Austria and Switzerland on their travels. In Holland, in 1980, they played at Paradiso in Amsterdam, the Brak at Venray, and also the Groningen Festival.

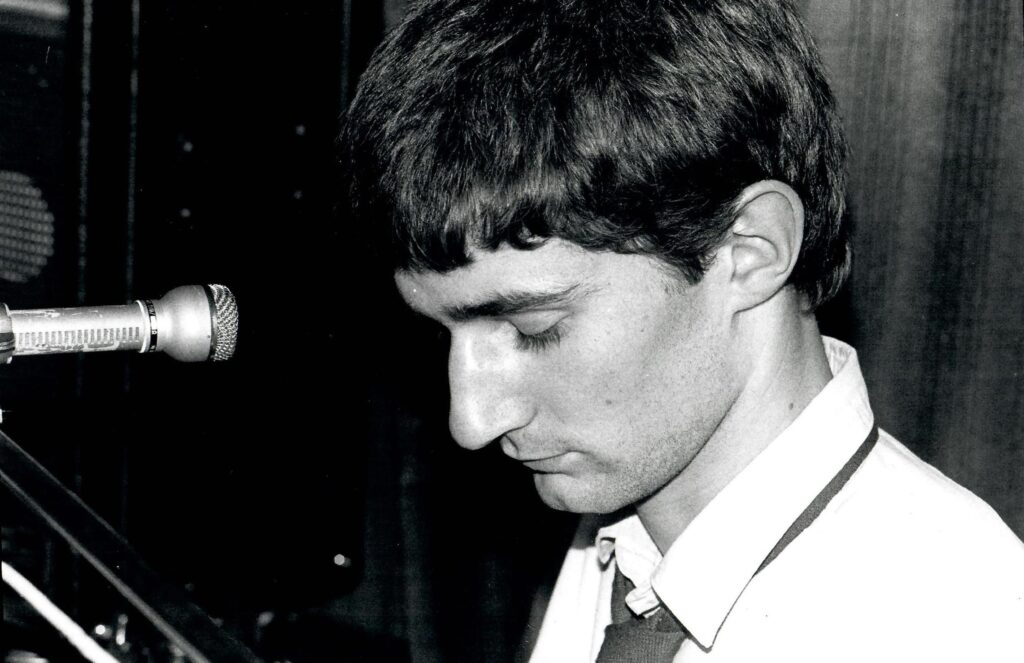

On the BBC television weekly The Old Grey Whistle Test in January 1980, Sore Throat performed Wonderdrug and Off the Hook: “Save your money for a rainy day and buy yourself a new Rolls Royce.” With Greg and Matt resplendent in blue lamé jackets, presenter Annie Nightingale expressed surprise that a band so good was not better known. She noted that Sore Throat had been in existence for five years, and had released their first album the previous autumn. The band were at their best that night, with Justin Ward playing the Whistle Test theme tune on harmonica. Greg Mason was on saxophone, Reid Savage on guitar and Clive Kirby on drums, while Dan played bass guitar and Matt keyboards. However, behind the scenes, all was not well and that same night Justin Ward abruptly departed the band, causing a tour to be cancelled and further album deals to be put on hold. Sore Throat continued on, with Matt and Dan sharing the singing roles. Their successful single Diggin’ a Dream was released in April 1980. In August of that year drummer Clive Kirby left, to be replaced by Nick Pepper, with guitarist singer/songwriter Conrad Warre also joining the band. Both Warre and Pepper had previously been in One Hand Clapping.

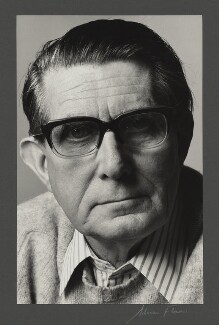

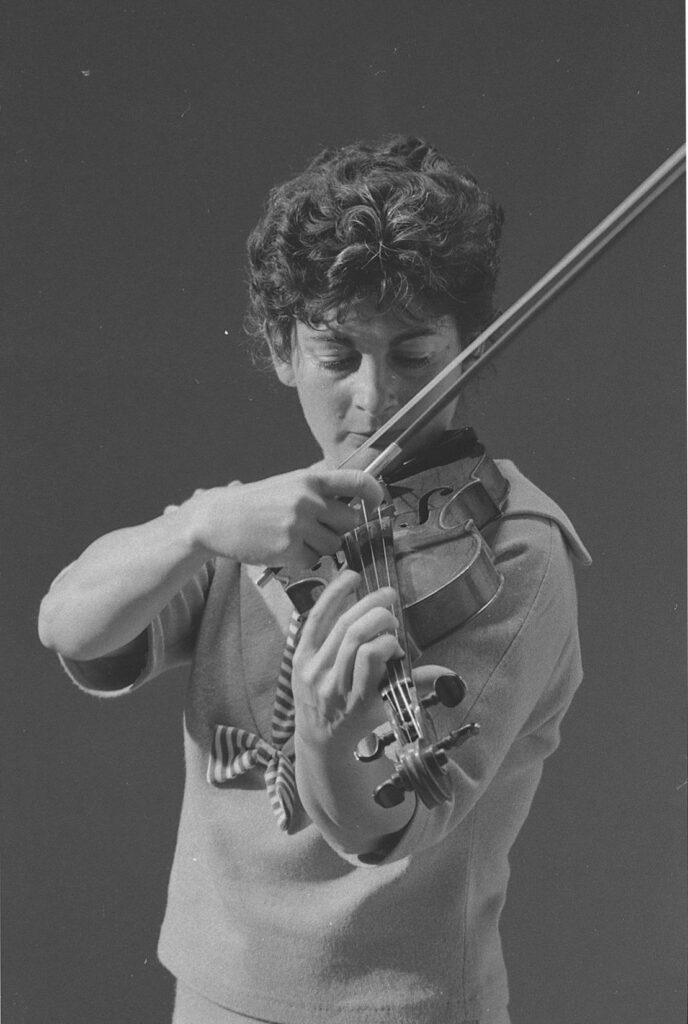

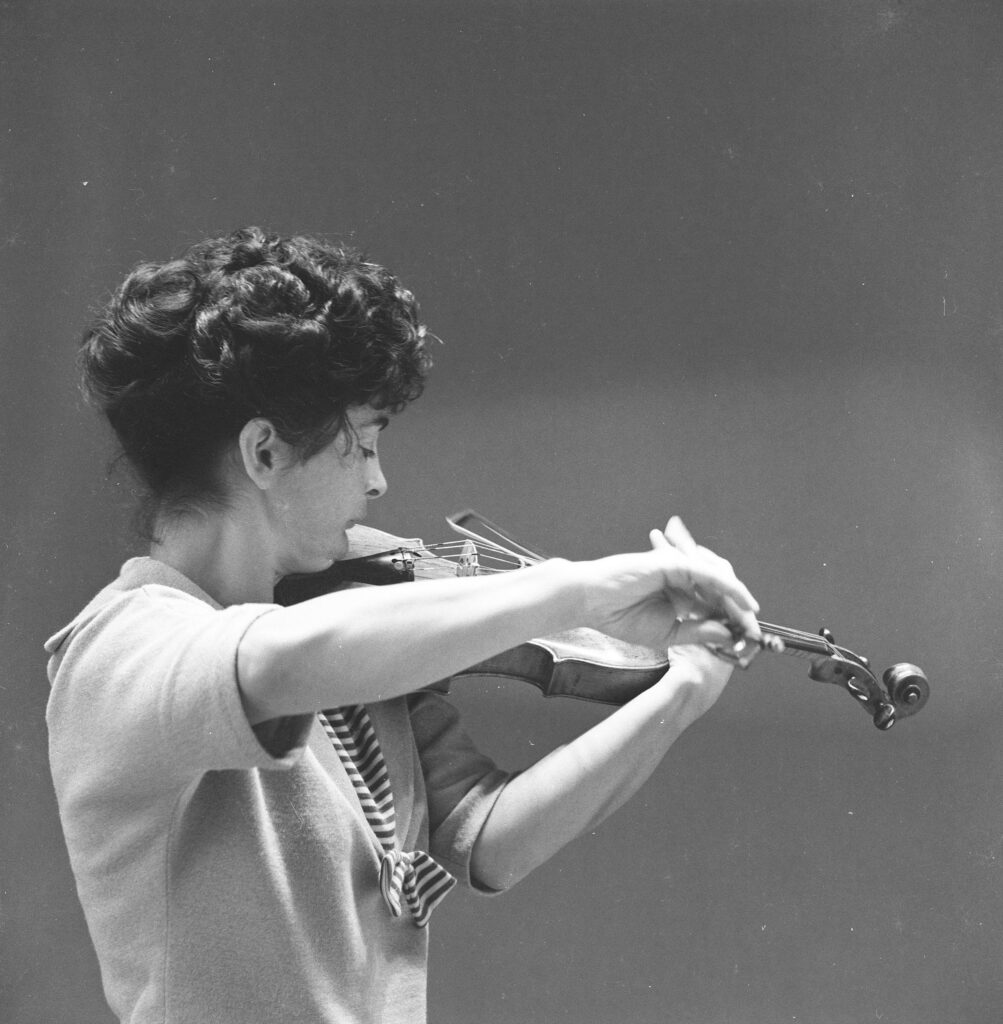

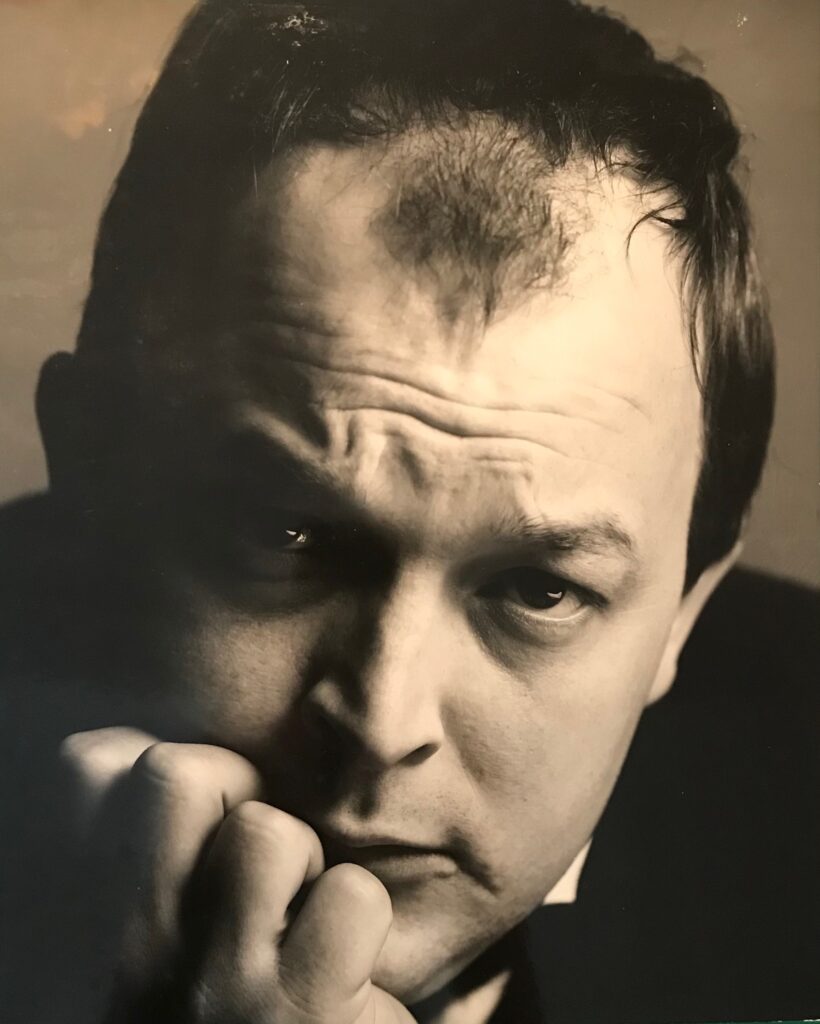

Photograph by Adrian Flowers.

Through these intensive years of performance and recording, Sore Throat’s music had evolved from punk/new wave into a more complex reggae/jazz fusion sound. However, they only issued one more single, Bank Raid, in June 1981. A third Flowers brother, Adam, occasionally played saxophone with the band. But with Conrad Warre increasingly dissatisfied with business arrangements, and with the departure of Reid Savage, the band’s final gig was held at the Greyhound in October 1981. Matt and Dan continued to perform as a rock duo, under the name Mattandan. Matt went on to play keyboards with Blue Zoo, appearing twice on Top of the Pops and their “Cry Boy Cry” was in the charts for eight weeks.

A reunion of sorts three decades later, with Dan Flowers, Greg Mason, Reid Savage and journalist Neil McCormick, re-branding themselves as Groovy Dad, took place in 2011. One of their gigs was at the Flowers Gallery, now being run by Matt.

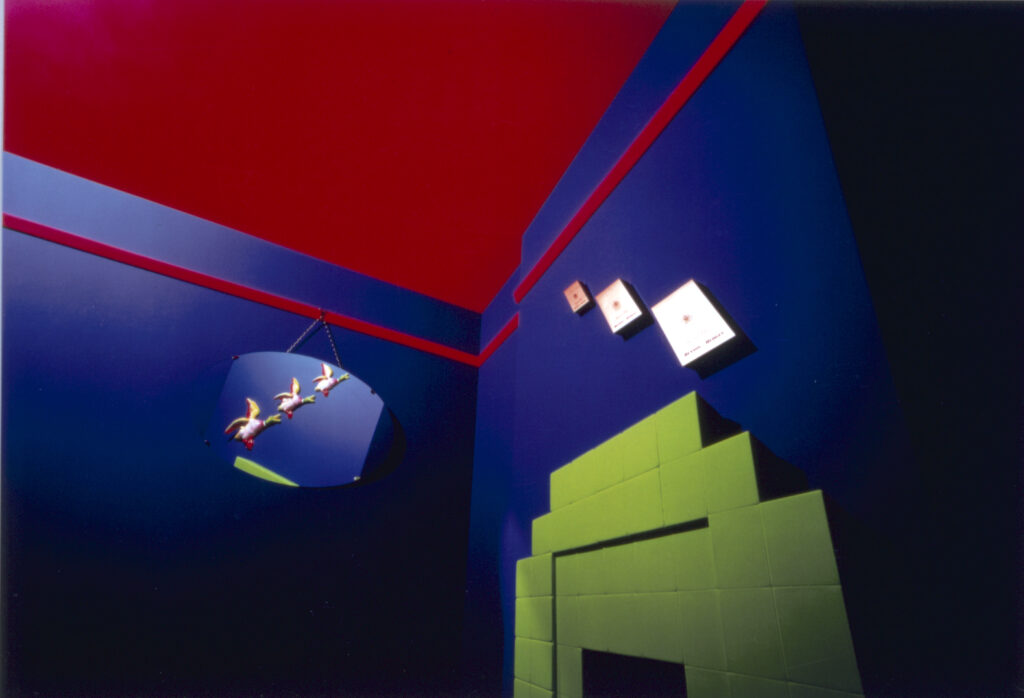

Photograph by Adrian Flowers

Text: Peter Murray

Editor: Francesca Flowers

All images subject to copyright.

Adrian Flowers Archive ©